An excerpt from Ashok Lahiri’s new magnum opus on independent India’s economic history

Ashok Lahiri is among those few policymakers who can take credit for having shaped India’s economic history in recent decades. The economist, who is now a member of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly from Balurghat, previously served as 12th Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India. Today, he is also a member of the Fifteenth Finance Commission. He has also been a reader at the Delhi School of Economics, executive director at the Asian Development Bank, chairman of Bandhan Bank and director of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy – apart from stints with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as a consultant and senior economist, respectively.

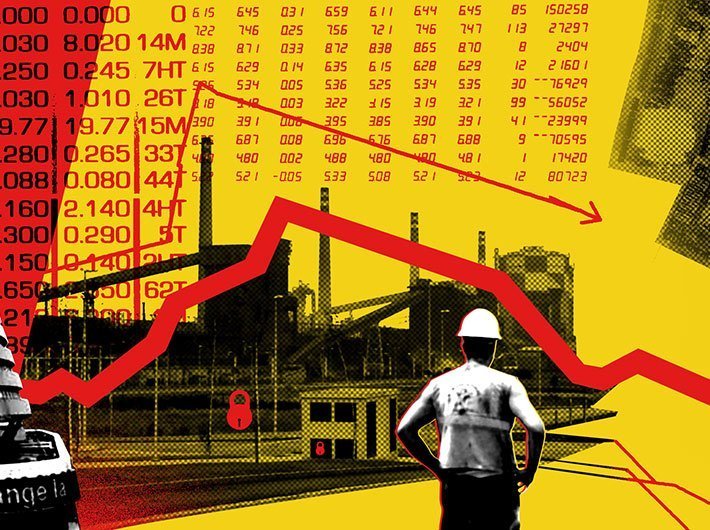

Distilling his learnings from this rich and varied experience, Lahiri has now penned ‘India in Search of Glory’ (to be published by Penguin this month).

India and Indians have made some progress over the last seventy-five years since Independence. The literacy rate has gone up. The Indians have become healthier, and their life expectancy at birth has also gone up. The proportion of people below the poverty line has halved in number. But the shine from the story fades when development in India is compared with that in the Four Asian Tigers and China. It looks good, but not good enough. India looks far away from the glory it seeks. This is the core subject matter of India in Search of Glory.

Here is an excerpt from the new work:

Political Calculus in a Maturing Democracy and Rapid Development

Evidently, political fortunes of incumbent governments continued to be determined not by their economic performance alone; the interplay of politics and economic policy was a variegated one, with multiple layers. Democratic politics in India was, and still is, constrained by its social cleavages in terms of ascriptive group identities such as language, caste and tribe. These cleavages have not disappeared but, with the spread of literacy, higher incomes and urbanization, only blurred. People are increasingly casting their votes and not voting their castes, but the salience of regional parties based on caste, for example, has not vanished.

In-group loyalties can bias electoral responses to not only inappropriate policies but also to corruption of elected representatives. People’s changing attitude to corruption at high places illustrates the changing in-group loyalties as well. Corruption had plagued India right from the early 1950s and 1960s, but allegations of corruption did not affect electoral results significantly in the beginning. A perceptible change in people’s tolerance of corruption came from the late 1980s. Alleged corruption is likely to have contributed to the defeat of the Congress under Rajiv Gandhi in 1989 and under Narasimha Rao in 1996, and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) under Jayalalitha in Tamil Nadu in 1996. After the Bihar fodder scam, Chief Minister Lalu Prasad Yadav had to resign and hand over the post to his wife Rabri Devi. 4 The fodder scam may have effectively ended Lalu’s political career, including, by his own admission, his dream of becoming the Prime Minister. Corruption issues are likely to have contributed to the defeat of the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) in the 2014 Lok Sabha election. People have become less forgiving of corruption, irrespective of the perpetrator’s caste, tribe, religion, region or group, and information about alleged corruption has become easier to obtain with the RTI Act. Proving such allegations and getting the perpetrators convicted, however, continue to be problematic.

Admittedly, communal riots break out at times and raise questions about how far India has succeeded in its nation-building endeavour. This book argues that with caste consolidation among the Hindus—which is a welcome development on its own—religion-based conflicts and

politics may increase for some time before starting to decline. Managing the religious cleavages in India will continue to be a challenge for Indian democracy in the short to medium run until caste consolidation nears completion among Hindus. The good news is also that communal

conflicts are likely to go down as caste consolidation nears completion.

It argues that the process of establishing communal harmony is a work in progress. While there are ups and downs, with economic growth, the spread of education and urbanization, the prospect of communal amity in the long term looks bright.

At the root of the lack of emphasis on collecting enough revenues and spending enough on, and implementing schemes of, social and physical infrastructure is the compulsion of democratic politics. In a democracy, to mobilize votes and win elections, politicians respond to what people

demand, and politics through promise of subsidies has not disappeared.

The iconic populist All-India Trinamool Congress (AITC) leader and chief minister of West Bengal, Mamata Banerjee, had resolutely rallied against rationalization of petroleum prices in 2000 and of railway passenger fares in 2012. As a UPA ally, in 2012, she had also demanded that the number of subsidized 14.2 kg liquid petroleum gas (LPG) cylinders be raised to twenty-four. She swept the 2021 Vidhan Sabha polls in West Bengal on the promise of free food, housing and monetary allowance for all. Ahead of the Vidhan Sabha polls in Uttar Pradesh, which he swept, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath (from BJP) slashed the power rate for farmers by half.

Social fragmentation is known to result in higher subsidies and lower demand for public goods such as education, health and physical infrastructure. Such fragmentation is getting blurred with economic development and migration. Furthermore, slowly and surely, the fact that subsidies are not manna from heaven and any subsidy to a particular group has to be paid for or financed by the others have become clearer to people.

There are already indications of democracy and democratic norms taking root, people asking not for doles and subsidies for their special groups but for education, health, and physical infrastructure such as uninterrupted quality power supply, roads, and supply of safe drinking water. The demand for ‘roti, kapda, makaan’ (bread, clothing and shelter) has slowly been replaced by the demand for ‘bijli, sadak, paani’ (electricity, roads and water). Electoral politics is moving away from identity politics and into debates about serious economic and policy reforms.

This book argues that Indian democracy will start delivering better outcomes as ethnic identities lose their relevance. The many-faceted Arun Shourie, economist, journalist, author and politician, famously said, ‘Governance is not golf: that we are a democracy does not entitle us to a handicap.’ We may appear to be dangerously close to justifying India’s painfully slow pace of economic progress by adducing her democratic system as an excuse. But we are not. The economic development of a poor country is not a 100-metre race but a 42-km marathon. What we argue is that democracy may have led to a slow start, but it is premature to pass a final judgement on the likely outcome in India. India lacks the strong physical infrastructure, such as roads, power and water supply, that authoritarian China has built up, but what it has developed and sustained is a strong institutional infrastructure in terms of separation of powers

among legislature, executive and judiciary, rule of law, and freedom of press. Policies in India will increasingly reflect the progress of the average Indian in terms of education, health and awareness about the effectiveness of policies, not only in India but in other countries as well.

When the Voting Rights Act of 1965, to give black Americans in the USA the ‘weapon—the vote’, was passed after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, an elated President Lyndon Johnson said this would give the power to the African Americans to ‘do the rest for themselves’. Did it solve all the problems for the African Americans in the USA overnight? No. But, ‘Forty-three years later, a mere blink of history’s eye, a black American, Barack Obama, was sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office.’ Similarly, pluralist politics and adult franchise has not only reinforced Indian nationhood, but gradually ushering in progressive policies also irrevocably changed Indians themselves, allowing democracy to work better and deliver appropriate development outcomes.

In India, while democracy has served well in building the nation, socio-economic development has been somewhat tepid in the first seven decades after Independence. But, as Indian democracy matures and people benefit from higher incomes, less poverty, more education and urbanization, such development is likely to accelerate. This book argues that as democracy matures in India, the political calculus of attracting electoral support from these changed Indians is likely to help the country in its search for glory.

[The excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.]