Pratapgarh changed Nehru. But Nehru (or his successors) could not change this part of Uttar Pradesh which still awaits its tryst with destiny. Meanwhile, feudal lords like Raja Bhaiya fill up the governance vacuum

At the stroke of the midnight hour on August 14, 1947, when Jawaharlal Nehru spoke of India’s tryst with destiny, Pratapgarh—barely an hour’s drive from his hometown of Allahabad—decided to miss that date with India’s independence. In the 65 years since then, India has evolved into a democracy, warts and all, but Pratapgarh has no warts at all because it has no democracy either. Firmly in the grip of feudal lords, Pratapgarh, thus, has enjoyed true independence: independence from the rest of the socialist secular democratic republic of India.

To trace the roots of Pratapgarh’s missed date with democracy, one can turn to social scientists and their data, or one can just turn to Badri Singh, a master raconteur who is as old as independent India. A resident of Balipur village in Kunda subdivision of Pratapgarh district (Uttar Pradesh), Badri’s stories are a curious mix of myths and legends about the all-pervading feudal families that have kept Pratapgarh out of the purview of silly modern notions of statehood such as democracy and the will of the people.

Take, for instance, Badri’s story about the might and valour of the grandfather of Raghuraj Pratap Singh, alias Raja Bhaiya, the 45-year-old undisputed political leader of Kunda. “The maharaj was seven-foot tall... he had dark complexion. He was so powerful that if he held the rear fender of a car, the driver couldn’t move the vehicle even on full rev.” In Badri’s memory and imagination, the feudal lords have all the attributes of god: they are omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent.

In his total devotion and faith in the feudal lords, Badri is not an exception. Rather, he is the norm; not just for the poor, ordinary, emaciated populace at large but also for the local police and the bureaucracy with all their trappings of state power. Raja Bhaiya is the state because the state as we know has abdicated its responsibility. Officers like deputy superintendent of police (DySP) Zia-ul Haque — who was killed while on duty on March 2 for daring to stand up to Raja Bhaiya — are exceptions who cannot be allowed to remind the erstwhile state of its erstwhile grandeur or responsibility. That Raja Bhaiya had to step down as a minister in the Akhilesh Yadav government after the murder and that the central bureau of investigation (CBI) is now probing it are minor details in an elaborate charade of apparent submission to constitutional democracy because constitutional democracy provides the cover for their lordship without stirring the conscience of the system.

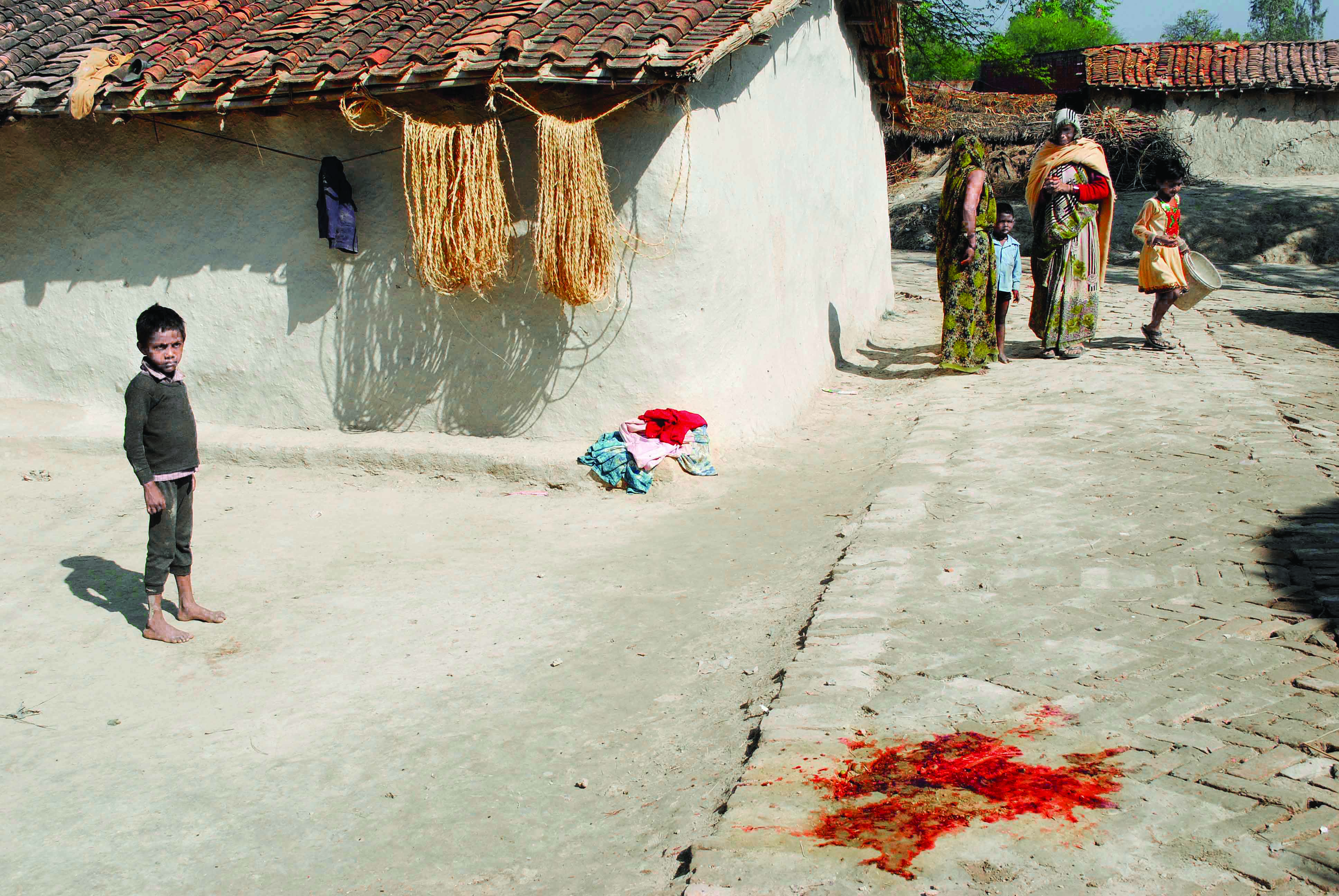

To understand fully the hold of the feudal lords in Pratapgarh district of Uttar Pradesh, Kunda sub-division, Raja Bhaiya’s political theatre and criminal enterprise, is a good place to start and the galling murder of DySP Haque the perfect setting to understand how the feudalists manipulate democracy. So a tour of the crime scene in Balipur village (of Kunda sub-division) is quite in order.

THE CRIME

Just like our storyteller Badri’s umpteen tales that build myths around facts, in Balipur village narratives about the crime are many and mostly based on the uncanny tendency of the people to trust fiction more than reality. What is significant is that all narratives discount outright the role of Raja Bhaiya, who hails from the erstwhile princely state of Bhadri and has been winning the Kunda assembly seat successively since 1993, mostly as an independent.

Yet, what the various aspects of this shocking crime unravel is a more shocking story of Nehru’s next-door neighbour waiting for that tryst with destiny, with democracy and governance that shall never come.

Late evening on March 2, Nanhe Yadav, gram pradhan (village head) of Balipur, was shot dead by two unidentified men at a crossroads near the village. It triggered a violent protest from his extended family. His brothers suspected that a villager named Kamta Prasad Pal was involved in the killing, and set his house ablaze.

When DySP Haque reached the spot two hours after the murder, he faced a hostile crowd of Yadavs. They chased away the police party accompanying Haque and started beating him. In the chaos Nanhe’s brother Suresh was killed by a bullet — fired from a country-made pistol, according to the police. Haque was also shot dead point-blank, again using a firearm not belonging to the police as per the post-mortem report.

These bare facts of the crime scene scratch just the surface of the complex crime. To get to its root causes, one needs to know the antecedents of the victims and their relations with Raja Bhaiya. Because, though Raja Bhaiya was nowhere in the picture, the curious reality of Kunda is that Raja Bhaiya is nowhere and everywhere at the same time.

Nanhe Yadav and his brother are both history-sheeters involved in many serious crimes. Significantly, both owed allegiance to Raja Bhaiya. During the past five years, as Nanhe developed a close association with Raja Bhaiya, his social, political and financial status grew meteorically. In a village of 1,000-odd people, mostly Kurmis and Pasis, and where the Yadav households count for not more than ten, Nanhe’s rise was thanks to his perceived proximity to Raja Bhaiya and his criminal antecedents. This, however, caused heartburn to a Rajput neighbour, Guddu Singh, who works as Raja Bhaiya’s driver in Lucknow.

Nanhe built a large house for himself and was building two more for his family members. After he was elected as the gram pradhan, he acquired political clout too. He started an intermediate college and also got involved in real estate deals as land prices skyrocketed.

Recently Nanhe bought a piece of land, mired in a court dispute, from a brahmin who had forcibly occupied it, though another villager, Kamta Prasad Pal, claimed to be its owner. Nanhe’s intention obviously was to make a fast buck by intimidating the real owner to give up his claim. Intimidation was not difficult: he had managed to secure licences for three firearms despite his criminal record, thus flaunting his influence with the local police. Pal then would have easily given in, but for the intervention at this point by Guddu Singh — to help Pal, his neighbour, and also to challenge Nanhe Yadav and establish himself as the real power centre because he has a reputation for being as a sort of “mini Raja Bhaiya” who tries to influence village politics in a manner that suits his boss.

Since such disputes are often referred to Raja Bhaiya’s ‘durbar’, which he regularly holds in his palatial house at Benti in Kunda, this case also came up for his hearing there. Normally, Raja Bhaiya dispenses instance justice in his durbar. But given Guddu’s inclination to protect Pal and the fact that two of his acolytes were jostling over this case, Raja Bhaiya is reported to have directed Nanhe to restrain from carrying out any work on the disputed plot and wait for the court’s order, a convenient submission to constitutional norms. In Kunda, Raja Bhaiya’s word is final and defiance entails a heavy price. Significantly, the state has willingly ceded its authority to Raja Bhaiya, whose tyranny is seen as a benevolent substitute for all the institutions of democracy and governance that exist only in name in Kunda (and all of Pratapgarh).

Villagers say that only a few days before March 2, an infuriated Nanhe had roughed up Pal for taking the matter to Raja Bhaiya’s court. Pals are a cattle-rearing sub-caste, forming a somewhat inconsequential segment of the village society. There are only five Pal households in Balipur and their source of livelihood is only land, rearing of animals and manual work in the fields of dominant castes like Yadavs, Patels and Rajputs. On the other side was Nanhe, who gradually emerged as another power-centre in the village with his clout growing further after a Yadav became the chief minister.

Nanhe was thus confident of having his way in dealing with Pal — till he met his nemesis in Guddu, who has cultivated his persona in the image of his employer and wanted it protected at all cost.

Guddu was enraged that Nanhe attacked Pal, his protectee. Though he must have seen it as an open challenge to his authority in the village, for political reasons he portrayed it as defiance of Raja Bhaiya’s call for a moratorium. Nanhe, of course, recognised Raja Bhaiya as his mentor, but was unwilling to take orders from Guddu since he considered himself more influential than this “mini Raja Bhaiya”.

Going by the versions of events given by police and villagers, Nanhe’s murder seems to be a sequel to his defiance of Raja Bhaiya’s reign, which is practically run by the “mini Raja Bhaiyas”. As per the police, Nanhe was shot dead by two motorcycle-borne assailants, presumed to be Pal’s sons. Given their background (the Pals of the village have no criminal record), it seems quite impossible for them to turn into professional criminals overnight and acquire guns and guts to shoot dead a powerful — and criminal — village head.

Re-enter, our master raconteur Badri: “The Pals are incapable of killing even a mosquito, let alone a powerful man like Nanhe.” He stops short of saying anything about who he thinks the real culprits might be, and to whom they may owe their allegiance. As for the royal leader, he says, “Raja Bhaiya is too big to get involved in such small things.”

On the other hand, inspector general (IG) of police (Allahabad zone) Alok Sharma points out that the manner in which Guddu prepared his alibi — by withdrawing money from an ATM in Lucknow and making phone calls exactly at the time these murders took place — was unusual to say the least. “His rivalry with Nanhe was known in the village,” Sharma says.

He, however, adds that it would not be appropriate to make guesses since the case was referred to the CBI.

Raja Bhaiya and his associates were far away from the village at the time of the crime but that could also be a carefully prepared alibi. Sources close to Raja Bhaiya pointed out that soon after the killings, he himself drove to the residence of chief minister Akhilesh Yadav and informed him about the incident. “The CM came to know about it from Raja Bhaiya and not from the police,” a source said, adding that had Raja Bhaiya been involved, he would not have done so.

However, a senior police official pointed out that the fact that the news of the killing of a DySP was first transmitted to Raja Bhaiya was an indication of the involvement of people close to him. It is ironical that Raja Bhaiya’s godlike attributes — he knows everything and nothing happens in Kunda without his wish (“patta bhi nahi hilta hai”) — raise suspicions about him in this instant case.

OFFICER OF LAW IN LAWLESS LAND

While Nanhe’s murder appears to be the direct fallout of village rivalry, the other two murders have all the elements of a sordid tale of thorough criminalisation of governance at the ground level. Zia-ul Haque then comes across as a dutiful and conscientious officer who rubbed Raja Bhaiya the wrong way by booking some of his acolytes for carrying out illegal sand mining near Kunda. Sand mining, a lucrative business here, is monopolised by petty contractors close to Raja Bhaiya. They emulate their mentor and conduct themselves as “mini Raja Bhaiyas” in their own domains.

Haque’s overzealousness to establish the rule of law was deemed to be an indiscretion that defied the “hegemony” of Raja Bhaiya and his associates.

Moreover, Haque was also investigating a bout of communal violence in neighbouring Asthawan village following the rape of a dalit girl. The idealist officer was doing his job diligently without fear or favour. The investigation obviously caused discomfiture to those involved in stoking communal trouble. Most of them owed allegiance to Raja Bhaiya.

In the collective psyche of the people of Kunda, such indiscretions are not only unacceptable but also to be met squarely with quick retribution in order to perpetuate Raja Bhaiya’s dominance. Haque was aware of what he was up against and refused to relent and pay obeisance to Raja Bhaiya at his “durbar”, a ritual which has been formalised almost as a constitutional obligation after Raja Bhaiya took over as a minister in the Akhilesh Yadav government. But Haque’s obstinacy to avoid this ritual, apparently to uphold the majesty of rule of law, was seen as impudence not only by his seniors in the force but also by the junior staff who are forced to accept the reign of Raja Bhaiya for one reason or another, but mostly because while senior officers like Haque come and go, they have to contend with him for all times to come.

Haque’s presence at the melee following Nanhe’s murder provided the ideal, unplanned opportunity for Raja Bhaiya’s minions to please their boss.

IG Alok Sharma gives a glimpse of this trend when he says, “Raja Bhaiya never contacted me on the issues related to police or crime. He called me only two or three times to ask about the food and civil supplies for the kumbh mela (he held the portfolio of food and civil supply).”

He, however, admits that since Raja Bhaiya was a minister, he could have easily thrown his weight around in Lucknow to get his things done. Obviously, there is a general impression of Raja Bhaiya among top bureaucrats that he is a good friend and a bad enemy to have.

Sharma acknowledges that when Haque was trapped in Balipur, his team of inspectors and constables ran away and made no effort to save him. “What is really surprising for me is why Haque did not try to fight back and fire at the assailants from his weapon,” Sharma says while making it clear that it was not unusual for police colleagues to run away to safety even if their seniors are trapped. “Have you not heard of IGs, SPs and senior officials getting killed in such a scenario?” he asks.

In the same breath, he admits that in Kunda, police and the state machinery are usually hesitant to act. “I came across such a situation when I reached Asthawan village. Hutments of the minority community were set on fire by an irate mob and hundreds of policemen were watching helplessly till the time I reached the spot.” he says, alluding to the prevailing perception among local police of the risk in going against Raja Bhaiya’s diktats.

This perception jells with the popular belief in Pratapgarh that Raja Bhaiya and other feudal lords are exempt from the law of the land. According to our story-teller Badri, “Raja Bhaiya’s ancestors and the rajas of Kalakankar were legally allowed by the British to murder at will — as they say, ‘saat khoon maaf’.” Most state functionaries today seem to see in Raja Bhaiya a continuation of this tradition. That India got rid of the British some 65 years ago is a minor detail that Kunda chooses not to acknowledge.

Also, the fact that Haque was trapped and killed while his team deserted him has its genesis in the prevailing political culture which has evolved its own code of jurisprudence. The manner in which evidence related to the crime was obliterated clearly indicates involvement of professionals. “Even the bullet that pierced Haque and his service revolver are untraceable,” says IG Alok Sharma who carried out an intense search with scanning machines all around the village to trace the weapons used in the crime. “It is not the job of an amateur,” he concludes from his preliminary investigation.

Given Raja Bhaiya’s godlike presence in the area, it is unimaginable for professional criminals to operate here without his consent.

NEHRU’S TRYST WITH PRATAPGARH

Raja Bhaiya and Kunda are just a part of the Pratapgarh story. History bears out the fact that the feudal lords of Pratapgarh were not only oppressive but also averse to the nationalist movement. In his autobiography, Nehru describes his visit to Pratapgarh in June 1920 as an event that changed the course of his life. He writes, “A new picture of India seemed to rise before me, naked, starving, crushed, utterly miserable. And their faith in us, casual visitors from the distant city, embarrassed me and filled me with a new responsibility that frightened me.” The acute poverty of the landless peasants and their exploitation by their feudal masters moved Nehru so much that he gave up his expensive lifestyle and adopted the district as his political nursery.

Nehru might have changed, but Pratapgarh has stubbornly refused to. Today, close to a century after Nehru’s visit, a casual visitor to the district would only see the enormous clout of money and muscle wielded by feudal lords and politicians across the district. For instance, the local MP, Ratna Singh of the Congress, is known as “Rajkumari Sahiba” as she belongs to the Kalakankar estate. Her father Dinesh Singh was a close associate of Indira Gandhi and had served as foreign minister in successive governments.

People’s interaction with their feudal masters is minimal. This lack of personal contact is adequately compensated by building myths around the rulers. One myth has it that these feudal masters never set foot on the soil: they fly all the world and land in and take off from their palatial houses! Be it Ratna Singh, Raja Bhaiya or Akshaya Pratap Singh, the Samajwadi Party leader from Raibareli who is a member of the legislative council, people see a royal halo around them.

What strengthens their larger-than-life image is the legitimacy they have gained by winning elections and retaining their stranglehold on people and all the apparatus of the state and governance. This is why Pratapgarh remains one of the most backward districts on the development indices (see box). There are hardly any industrial units in the district and agriculture remains the economic mainstay. Of late, the district has made progress on the farm front, promoting orchards of mango and amla (Indian gooseberry). Yet these resources remain confined to the handful elites. All owners of big orchards are from either feudal families or powerful political families. The local political economy revolves around agricultural land, real estate and government contracts which are completely monopolised by the likes of Raja Bhaiya.

That the same few influential families are owners of vast tracts of land and palatial houses built over hundreds of acres speaks eloquently about the complicity of successive democratic governments in perpetuating their hegemony. They seem to be singularly exempted from the Land Ceiling Act. The family of legendary Congress leader Neyaz Hasan who represented the Kunda constituency for three decades till the 1990s owns one of the biggest mango orchards in UP. The palaces of the erstwhile feudal families of Bhadri, Benti, Pratapgarh and Kalakankar mock the laws pertaining to jamindari abolition and land ceiling.

The only serious uprising against the feudal lords by the landless peasantry of Pratapgarh, which was a part of the then Oudh region, took place in 1920. The movement led by Baba Ram Chandra petered out without any radical impact. Nehru was quite moved by the deep religiosity of the peasants who raised the banner of revolt against the feudal lords with a full-throated invocation of “Sita Ram”. People of this region, not far from Ayodhya, are deeply devoted to Ram and Sita, and the influence of the Bhakti tradition makes these social underdogs easy prey for feudal myths.

The innocent faith that impressed Nehru attained a perverse form with the emergence of various shadowy ashrams in the area. In March 2010, 63 people died when Kripalu Maharaj, a dubious saint with immense financial and political clout, organised a fair to distribute freebies to the poor in Pratapgarh. The power and pelf of the feudal lords and influential political leaders is matched only by the capacity of such ashrams to distribute doles to the gullible poor. These feudal lords and dubious god-men complement each other in keeping the masses in their thrall perpetually.

Post independence, Ram Manohar Lohia made a determined effort to lead the landless people against their feudal masters but could make only marginal impact in little pockets as most of these erstwhile ‘princelings’ tactically aligned with the Congress. Given the legends of Dinesh Singh’s proximity with Indira Gandhi, Pratapgarh became out of bounds for any administrative or social reform by successive chief ministers. Even the Left has been unable to penetrate the district and surprisingly, there is not even a trace of Maoist presence here though the feudal lords of Pratapgarh would make for natural enemies of the left wing extremists. Such is the control of the feudal lords.

There are enough reasons to believe that the cult of the Raja Bhaiyas in the entire region has been promoted and sustained by none other than the state itself. It will be naïve to believe that Raja Bhaiya is an exception in Oudh region or Poorvanchal where many bahubalis (musclemen) continue to occupy social, political and economic space and run democracy according to their own vision of it. If Raja Bhaiya runs a parallel state in Kunda and has found acceptance among the people, his archrival Pramod Tiwari runs a rather sophisticated model of the same genre by winning elections from Rampur Khas for three decades without a break. Ratna Singh alias “Rajkumari” can claim to have her own model of winning people’s support. In an adjacent constituency, Akhilesh Singh with criminal antecedents, is the lord of all he surveys.

Pratapgarh represents a unique model of political consensus where the opposition is almost non-existent. Given the fact such pockets are enlarging their influence, the possibility of the Pratapgarh model extending to the entire state cannot be ruled out. In neighbouring Allahabad, for example, Atique Ahmed with an arm’s length of crime records, is a popular leader in his own right.

That these leaders are embraced by all political leaders is an index of their increasing utility in the country’s electoral democracy. Raja Bhaiya is as much acceptable to Rajnath Singh and the RSS as to secular Mulayam Singh Yadav or chief minister Akhilesh Yadav. If Rajnath Singh patronised him when he was the chief minister, Akhilesh Yadav’s first direction after assuming the post was to erase the criminal cases against Raja Bhaiya. That would not have surprised Badri Singh, who thinks that such leaders belong to a lineage that stands exempt from paying for crimes (“saat khoon maaf”).

The district that brought about a significant change in Nehru’s political life obstinately refuses to conform to his vision of India’s “tryst with destiny”. It in fact demonstrates that in not just tolerating but allowing it to thrive, India itself has defaulted on its date with destiny. Because, as a top IPS officer from Uttar Pradesh put it succinctly, Pratapgarh is but just a microcosm of all that has gone wrong with India’s democracy.

This reportage first appeared in the March 16-31 issue of Governance Now.