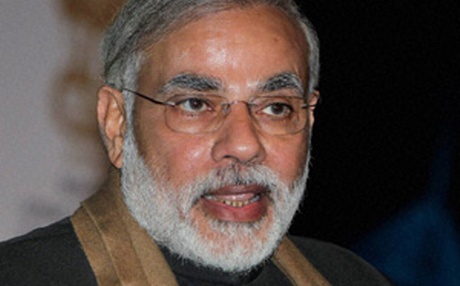

The animal spirit of the economy of Vibrant Gujarat reveals a lot about Narendra Modi’s navigation skills but also hides bits and pieces of reality that the state’s middle class prefers to delete from its daily discourse

In a state used to gambling daily on the number of squares on the coat of R K Laxman’s Common Man, it is hardly surprising to find many wagering on the outcome of the December elections. It is even less surprising that the gambling dens had picked Narendra Modi as the clear winner even before the parties named their candidates.

At the end of the democratic exercise of elections, intended no doubt to empower the people, some will make millions on the sidelines at the cost of the many. Life might be miserable for the latter but there are people who have made human emotions measurable – preferably in money. What else can explain bets on monsoon, the failure of which is a routine tragedy in many parts of the state?

Gujarat has enriched itself manifold over the last two decades of neo-liberalism. After Narendra Modi’s arrival, the pace has only become more furious, unleashing a spirit that has insatiable hunger for wealth. But this new culture of money stands in sharp contrast to the old-world Gujarati tradition, which combined entrepreneurship and moneymaking with thrift, religious philanthropy and even institution-building. Make no mistake, Gandhi’s Gujarat has changed (as has the rest of India). It is unfair to expect anything else 64 years after his death but you could still be in for a rude shock at the extent of change in culture and collective psyche of the state induced by the last decade’s growth and prosperity.

Take, for instance, the delight of the farmers near Vadodara over the spiralling value of their agriculture land. “The price of land has increased manifold in our village. That makes us feel quite rich,” said a father-son duo that supplies tobacco leaves to gutkha manufacturers. Asked if they would sell the land and encash the windfall, they said not immediately.

“But you feel good when your property price escalates,” the two added.

The high price is only in their thought bubble, not in their bank balance, but what they were expressing is the pervasive feeling across the state that Gujarat has never had it so good.

Overall a pretty picture

Driven by this animal spirit of the market economy creating not only personal wealth but also a constant craving for it, the state has been evolving a model which inspires awe and scepticism in the same degree. According to Purushottam Marvania, who teaches economics at Saurashtra University, history bears out the fact that such models are not sustainable. He points out that the drought-prone Saurashtra region posted unprecedented growth in the 1970s, thanks to a boom in the diesel pumping sets industry. This led to bumper yields in agricultural produce but the high growth story came with a cruel twist. Uncontrolled and unregulated pumping of ground water caused the water table to drop so drastically that water turned saline and farming became untenable within a decade.

On the face of it, the current phase of growth seems better founded. In recent years, propitious monsoons have helped Saurashtra recharge its depleted ground water. At the same time, access to irrigation has improved with the availability of Narmada water and far-reaching reforms in the power sector have ensured round-the-clock supply of electricity for irrigation. This has practically eliminated the polluting diesel pumping sets and helped recharge the water table even more. Farmers were persuaded to switch to cash crops leading to more prosperity and the industry was given tax sops to manufacture electric pumping sets (as against diesel pumping sets).

As of now, the industrial estates in and around Rajkot have become ancillary hubs for the growing automobile sector in the state.

But that pretty picture is showing signs of fraying at the edges in this election year. Saurashtra is very critical to Gujarat politics, as it sends nearly one-third of all legislators to the Gujarat assembly (58 out of 182). The monsoon has failed in parts of the state this year and the elections are being held against the spectre of drought and scarcity after many years of a good run. The switch to cash crops has contributed to a mind-boggling growth in agriculture (nearly 30 per cent in some years) and farmer prosperity, but it has set off warning signals elsewhere.

Production of cereal has taken a beating, requiring Gujarat to import nearly 30 per cent of cereal it consumes from other states. In a state battling very high levels of child malnutrition, this could extenuate the nutritional imbalance.

The government has picked child malnutrition as an area of focus and as a precaution against recurrent droughts thousands of check-dams and hundreds of small reservoirs have been constructed over the last decade and more. But Marvania is sceptical. “All these measures are woefully inadequate, as the region is facing a serious economic recession, not only on account of drought but also because of the curbs imposed on cotton imports by China,” he says.

It is too early for such sub-sonic signals of trouble to register in the din over growth and development. So they have done little to dampen the festive spirit of the people. What Raju Dhruva, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) spokesman for Saurashtra, said in a slightly different context sums up the situation: “Gujaratis are in the mood to celebrate now and celebrate they will, even if they have to take a loan to do so.”

And why not? Signs of opulence abound in Rajkot, which is known as the heart of Saurashtra and dominated by the Patel community. Crowds of people outside the city’s shopping malls, long queues outside expensive restaurants and over-booked five-star hotels are obviously not indications of an impending doom by any stretch of imagination. For the Gujarati middle class, display of big spending is the new fad. And this significant social chunk is averse to disturbing the status quo.

The sweet sound of money

So addicted is this section to money-making that it fails to register the social and economic fault lines. Three dalits, including two minors, killed in police firing following a caste clash (on September 22 in Thanagadh, Surendranagar district) is not the kind of news they would like to read in their newspapers. News for this class (like elsewhere in the country) begins with Sensex movements and ends with bullion prices.

This is why Saurashtra’s tallest Patel leader, former chief minister Keshubhai Patel, cuts a sorry figure in his campaign against Narendra Modi. Fulminating against Modi, he has been hurling accusations which only confirm his successor and bête noir’s credentials as an aggressive development campaigner. “He (Modi) is a liar and he has done nothing for Saurashtra,” Patel says while unravelling his own election promises: free electricity, free land for housing to weaker sections and many other sops which if implemented would spell disaster for the fiscal health of the state.

The Patel community, which has been politically marginalised by Modi’s advent, may have many axes to grind with Modi but it is highly unlikely that they will bank on 85-year-old Keshubhai to reclaim their political space. For one, the ground has moved since Keshubhai’s twice truncated stewardship of the state. Besides, farmers have now become used to paying for uninterrupted three-phase electricity, so the grammar of freebies is out of sync with the times.

Even Leuva Patels, Keshubhai’s own sub-caste, do not take his promises seriously.

A similar script, with its regional variations, could be gleaned from the reaction of people in other parts of the state. For Pinakin Desai in Surat, life has never been so smooth in and around his city. “You can see that governance of the district has improved substantially,” he said, and cited an example to qualify his statement. Surat, he said, is prone to dengue because of its proximity to brackish seawater. “Some weeks ago, there were rumours of an outbreak of the dengue. The health department moved in swiftly by collecting random blood samples from peoples’ homes for testing and arresting its spread,” Desai said. “It launched a massive awareness programme and attended to suspected patients immediately.”

As a result, Surat has been able to deal with dengue much more effectively than any other city. Surat has not just buried its old image of a filthy and disease-prone city but has become a model for urban renewal, especially in matters of sanitation. Similar stories of contentment and happiness are found in tribal areas like Dang or in industrial localities like Bilimora.

Undertones of grey reality

Of course, this narrative of Gujarat’s transformation hides the hideous face of other realities. The widening gap between the rich and the poor is ignored with a contempt that characterises the typical middle-class hubris. Take, for example, the publicity blitz that usually accompanies the holding of “Vibrant Gujarat”, a high-profile event to package the state as the ultimate resting place for the global dollar.

The 2011 edition of the conference was held at Mahatma Mandir, a fabulous and ostentatious convention centre in Gandhinagar, named after the saint who set up the Sabarmati ashram to incubate a unique social experiment for evolving a society without boundaries of caste, religion, colour, wealth and poverty. But on the drive to Mahatma Mandir from the airport, a stretch of road lined by slums was effectively fenced out of the global visitors’ view. Out of sight is out of mind.

Now, as Gujarat heads into an election on the twin plank of growth and development, it does not even need physical barriers to hide poverty. It has been so firmly knocked out of people’s mind that it is just not there in popular or political discourse. This unwillingness to acknowledge the existence of poverty has attained a certain social acceptance. Any attempt to allude to it is seen by the vocal and dominant middle-class as a conspiracy to unsettle the status quo and thereby undermine the Gujarati pride. The government’s social programme to provide affordable housing for the urban poor has effectively stimulated the wealth-accumulation instincts of even the weaker sections, thus completing the code of silence on poverty.

The “all is well” consensus is pervasive and striking. Such homogeneity of thought, desires and dreams is not in evidence anywhere else in the country.

Here, the intensity and diversity of the development debate has had an impact quite to the contrary, that of creating a craving for a modicum of consensus on the nation’s development agenda. Corruption, the bugbear of all political parties and governments across the country for the last two years, crops up in this election year only as an apology for development; easily dwarfed by the larger-than life stories of Modi’s decisive leadership and decision-taking that are now the stuff of legend.

Is this sense of well being, this consensus, for real or has it been forced? Why are there no discordant notes from Gujarat? Modi had addressed similar concerns two years ago in an interview to Governance Now and his responses are worth recalling because they are still as relevant:

GN: Your detractors say that you stifle voices of dissent. They also say that there is a contrived or manufactured social consensus in Gujarat, that is, you are manufacturing this consensus...

Modi: Let them come out with something new. Have you seen opposition leaders being jailed or silenced in Gujarat?....Then what is this manufactured consensus? What is wrong if everybody agrees on development? Do you mean to say that if we have 60/40 or 80/20 consensus/dissent, it is fine, but when you have 100/0, it is wrong? This is strange logic!

GN: Your detractors also talk about the authoritarian streak in your administration...

Modi: As I told you earlier, they have nothing new to say. When the voices of dissent have something new to say, they will be heard….

During the same visit, a respected Gujarat academic and an unabashed Modi-baiter had told Governance Now candidly and presciently: “We have lost the argument…. You will soon see the US and other countries courting Modi (he had become sort of pariah for the West post-2002 riots).”

How infallible is the God of Growth?

Two years later, that’s exactly what has happened. The envoys of UK and the US have made their first trip to Gandhinagar in 10 years to restart the conversation with Modi. And, obviously, in these two years, the voices of dissent have not discovered anything new to say because they have only been further marginalised.

It would be as unfair to deny Modi credit for decisive leadership as it would be naive to believe that poverty does not exist in Gujarat. What doesn’t exist is popular and political discourse on poverty, and issues related to the marginal sections of society. Any discussion on the alarming levels of child malnutrition, or the poor quality of education in primary and intermediate classes, is seen as representation of a counter-culture inimical to the state’s interests. Gujarat’s voices of dissent have been shushed into silence by a people unwilling to entertain any discourse other than the most pleasant.

That is perhaps why issues relating to the environment and ecology have found new interpretation in Gujarat’s relentless pursuit of growth, as is evident in the popular distaste for any protest against the furious pace of industrialisation along the coast or the industrial corridors that have come up across the state. These issues are not even on the periphery of the electoral discourse of any political party. In such a setting, friends and foes alike have only been idolising the existing Gujarat model.

In so doing, they have only been strengthening Modi inadvertently and making him into Gujarat’s infallible God of Growth. And Modi himself loves to explore the realms of Godliness thrust upon him by inventing new ways of being everywhere. If in 2007 the Modi masks did the trick, he is using technology to present himself in a whole new avatar by “appearing” in four public meetings in four corners of Gujarat at the same time, all the while sitting in his office in Gandhinagar!

No wonder that in Gujarat, Modi is all-pervasive. And Gujarat is in a deep trance. The development trance.