The killing of a seven-year-old boy at Ryan International School, Gurgaon, suddenly brought focus on violence by students in school. It was a gruesome case indeed: On September 8 last year, Barun Chandra Thakur dropped his children, including seven-year-old Pradyuman, at school around 8 am. By the time he reached home, his wife had received a call from school: a staffer asked her to call another school employee named Anju Dudeja. When she called Dudeja, she was told her son was bleeding from a cut to the throat and was being taken to hospital.

In the hospital, Thakur and his wife saw their son, whom they fondly call Prince, drenched in blood. Doctors told them he was dead. There was a deep cut extended from the ear to the neck. Doctors who performed the autopsy told police the cut was so deep, the child would have died within one or two minutes.

Comment: Reform rather than punishment should be the driving idea

After an investigative botch-up in which a school bus conductor was accused of sexually assaulting the boy and killing him, a Std XI student – a juvenile, aged 16 – stands accused of the killing to have a PTA meeting and an exam postponed. The initial probe was by Haryana police, but now it’s been taken up by the CBI, after a relentless demand by the victim’s parents.

According to sources close to the investigation, the accused brought a rusty knife to school, attacked the boy in the washroom, washed his hands, and stepped out, wiping his hands with a handkerchief. A Std IX student who knew him from music classes saw him and they shook hands cursorily. As the Std IX student passed the washroom, he saw a bleeding child crawling near the washroom, trying to prop himself up with support from a wall. The Std XI student, meanwhile, had gone and told a school staffer that something had happened to a child in the washroom. Senior staffers arrived, and with the help of a bus conductor, took the child to the hospital.

Since then, several incidents of violence by students in school have been reported and the clamour for harsh punishment for the juvenile has gone up. For some of these cases that came to attention are mind-numbing. On January 20, a Std XII student shot the principal of the Swami Vivekananada Public School in Yamunanagar, Haryana. She later died in hospital. He’d used his father’s licensed Webley-Scott revolver, an expensive and powerful handgun. The principal had apparently scolded him for not doing well in studies. And in Lucknow, a few days before the Yamunanagar incident, a Std VI girl student of the Brightland Inter College School stabbed a Std I boy, apparently to get a PTA meeting postponed or the school closed for the day. After this, there were debates on whether the Ryan assailant should be tried as an adult.

***

Psychologists and those who have worked with juvenile offenders say children absorb values, ideals and behaviour from their environment – from parents, friends, the neighbourhood, society, TV, and of course, the internet. The violence they see often percolates into them. This is as true for a child from a rich family as it is for one from a poor family. Quite often, it lies hidden below the surface.

Take the Gurgaon case. The accused was well-behaved and popular for his skill in music – he was good with the keyboard and would play during routine school assembly meetings and important programmes. Neighbours said he’d daily pray at a temple outside his house. He played with the children living near his house and had a good rapport with them. Investigators, however, said there was continuous pressure to perform well in studies from his parents. Sources in the juvenile justice board said the father, a working professional, and mother, a homemaker, would often quarrel and the boy had witnessed violence at home. “My parents fight a lot,” he is learnt to have told investigators. “When exams came, I used to get really scared. If I scored less, father will scold me a lot and will beat mother.”

According to teachers, the boy had once been hospitalised because he’d taken drugs. He would break the rule against bringing cellphones into the classroom. Investigators have also taken note of his friends saying that he’d been speaking about possible ways to have the PTA meeting or the exam postponed. One of the possibilities he mentioned, which friends probably did not take seriously, was poisoning a student. After the CBI arrested him, experts made a social and psychological review of the accused. A board looked at his case to determine whether he should be tried as an adult or a juvenile, in accordance with the juvenile justice law, which was amended to permit prosecution as adults of juveniles accused of serious crimes after a board evaluates them and the circumstances of the crime. In their report the board found that the juvenile had done pre-planning and they recommended for his trial as an adult. In the end, the board recommended that he be tried as an adult.

According to teachers, the boy had once been hospitalised because he’d taken drugs. He would break the rule against bringing cellphones into the classroom. Investigators have also taken note of his friends saying that he’d been speaking about possible ways to have the PTA meeting or the exam postponed. One of the possibilities he mentioned, which friends probably did not take seriously, was poisoning a student. After the CBI arrested him, experts made a social and psychological review of the accused. A board looked at his case to determine whether he should be tried as an adult or a juvenile, in accordance with the juvenile justice law, which was amended to permit prosecution as adults of juveniles accused of serious crimes after a board evaluates them and the circumstances of the crime. In their report the board found that the juvenile had done pre-planning and they recommended for his trial as an adult. In the end, the board recommended that he be tried as an adult.

***

If the Ryan case was taken up so hugely by the media, it was because it was a prestigious and expensive school, favoured by the upper middle class, and because it happened in the national capital region (NCR). Even the Yamunanagar case – where a student brought a revolver to school and shot at the principal – and the Lucknow case did not garner so much attention. There’s often so much violence by students in government schools that goes unnoticed. In these schools, violence by teachers and those in authority, too, is common. Lawyers, social activists and teachers say that many of the children landing up at juvenile homes are from poorer families and more likely to be enrolled in government or municipal schools. Some recent cases of violence by students at government schools have left teachers and students troubled, and afraid of what they might end up facing.

Some two months back, a teacher at a government school in east Delhi was locked up inside a washroom by a Std XI student. He demanded sexual intimacy with her and refused to let her go unless she gave in. She kept shouting for help and was eventually rescued. A complaint was lodged against the student. But the teacher remains traumatised.

In another school in southwest Delhi, a teacher was assaulted by a Std XII student while he was teaching. He was punched in the face several times. His glasses broke and he was injured in the eye. The teacher had scolded the student for taking drugs during a school trip a few days before. The student, afraid that he may be expelled from the school, had threatened the teacher before carrying through. The teacher, though hurt and humiliated, has taken it in his stride.

“At his age, it’s very common to want to try alcohol or smoking,” he says. “But if a teacher finds out about it, he has to warn them and take action. It’s a teacher’s responsibility, after all. Especially when the trip was planned by the school. That’s all I did.” According to him, there are lots of children in government schools who want to have nothing to do with education: they either join either as a formality, or because of pressure from their parents. “You’ll get to see the attitude of ‘We’ll take care of our lives. Why is it your business? How is it your problem if we don’t want to learn?’ in a lot of students nowadays,” he says.

“Perhaps they think there are alternative ways of earning and progressing in life. The urge to get ahead fast, without having to do much hard work is getting stronger among teens these days.”

A government school principal from north Delhi says violence against teachers is very common in state-run schools. Last year, he had to accompany a teacher to the police station to register a complaint after some students threw a large stone at him when he was getting out of his car. “It almost hit him on the head,” he says. “Another stone hit the windshield. Imagine what would have happened if the stones had not missed him. What could be the reason? He may have scolded some of them.”

Mukesh Kumar, a teacher at a government school in Nangloi in Delhi, wasn’t as lucky as that. In September 2016, he was stabbed to death by two students. One of them was then a minor, and the other 18 years old. The two had a grudge against the teacher: the minor had been rusticated twice from the school, the other was facing rustication. “The attacks on teachers that get public attention are less than 10 percent of the actual incidents,” says Ajay Veer Yadav, general secretary of the Government School Teachers Association of India. “Teachers do not take issues like threats and beating up forward. Students from families with criminal backgrounds have their family’s backing. Teachers fear violence. Some think their reputation will suffer. Getting beaten up by students can be embarrassing or humiliating.”

Yadav thinks there should be a special cell, committee or body to address such complaints. Speaking of the Nangloi case, he says, “There should be a way of ensuring teachers’ safety. We submitted a list of suggestions to ensure teachers’ safety, but we don’t see any action on the ground,” he says. “Many of the teachers in the Nangloi school sought transfers after the incident – they were so scared. And the students’ families threatened teachers against becoming witnesses, or else they’d be taken care of. We don’t have any witnesses in the case.”

***

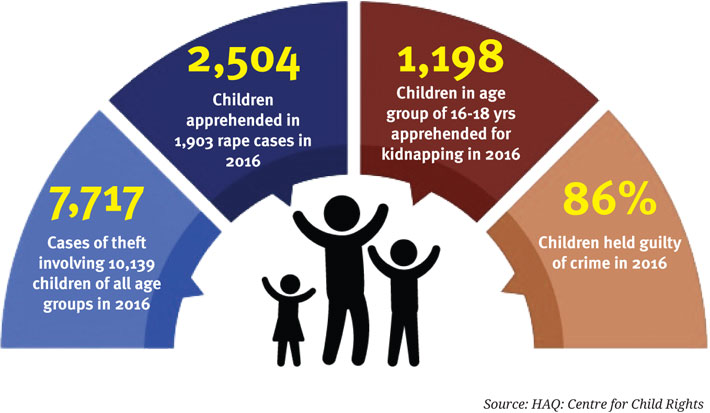

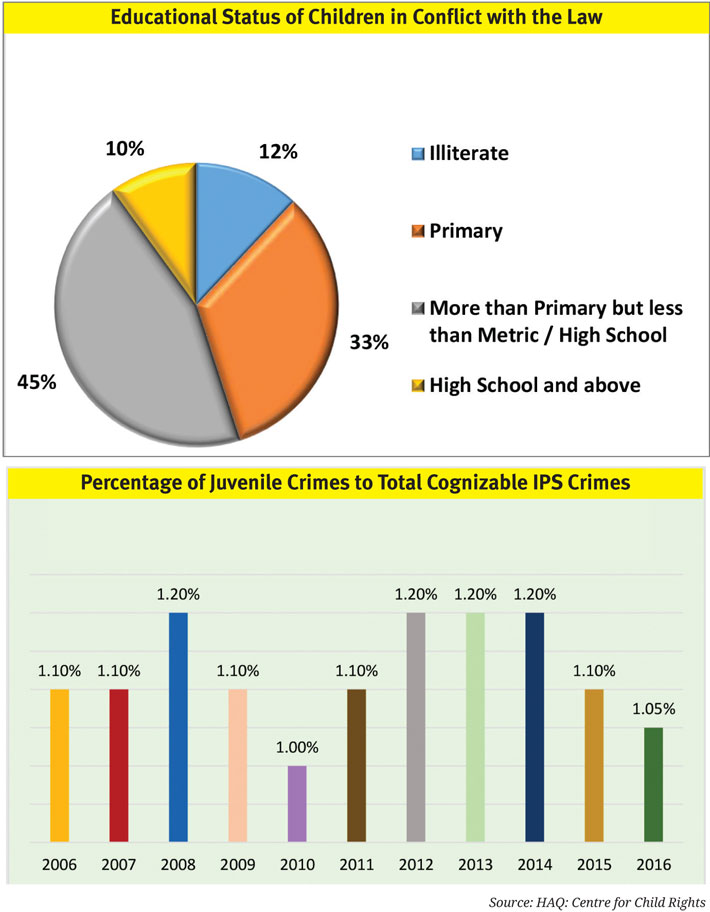

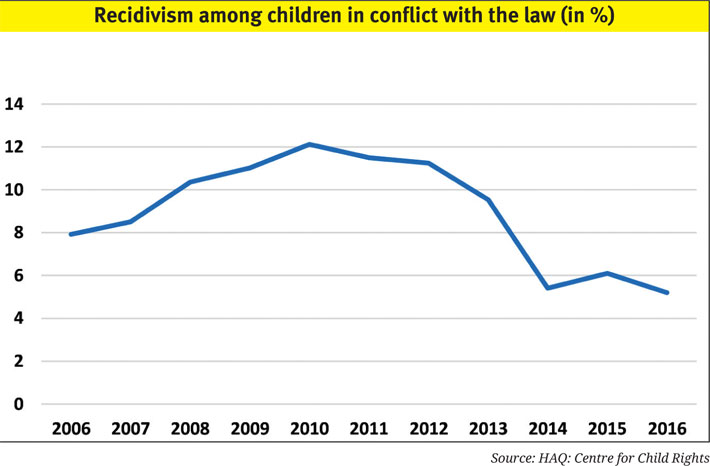

Experts say the figures don’t show a rise in juvenile crime; it’s only that some egregious cases have brought sudden focus on them. Amod Kanth, a former IPS officer who is now a social activist and general secretary of the Prayas Juvenile Aid Centre Society, says, “Children’s crimes are in proportion with adults’ crimes,” he says. “The percentage of heinous crimes constitutes only 0.7 percent of the overall national crime figures. It is, of course, a matter of concern, but it is not as alarming as is being projected.”

Kanth feels that children in government schools are particularly vulnerable to a criminogenic environment, owing to lack of parental control. “In private schools, the teacher-student ratio is relatively better. There is better supervision. The families are more concerned about children, so they are able to exercise better control. The impact of technology can be contained to an extent. Many children who commit crimes, usually from economically weaker sections, are enrolled in government schools, but they are not seriously engaged with the system.” He added that more than 14,000 juveniles have been through the observation home run by Prayas in the past 20 years, and roughly 95 percent of them belonged to lower middle-class or poor families. “They were the products of these schools – dropouts from these schools. The crimes are anyway reported more in the cases of the poor.”

***

It’s no one’s case that all juveniles under pressure commit crimes. But quite often the pressure can force them on to the path of crime, often mindlessly. “The problem is not the child, but the system that creates performance anxiety,” says Bharti Ali, co-founder of HAQ: Centre for Child Rights. “They are told by their parents to perform so that they can get in such and such college so in turn they can get the best job they want.”

As for the violence, Ali says it’s a sociological phenomenon: “They are shown from the beginning that certain kinds of violence are justified. They get the impression that it is justified to be violent to the ‘other’ caste, class, gender, religion or nationality.” Her colleague and HAQ co-founder Enakshi Ganguly concurs. “Why do the parents panic when they themselves teach the kids that it is okay to be violent and disrespectful with the maid?” she asks. “We are only addressing the symptoms. We don’t address the real problems. Why are there no discussions about forgiveness? Hate on television comes down to individual lives.”

Quite often, it’s a matter of chance – the sheer bad luck of intentions escalating into something larger and more dangerous than foreseen. In February, three minors were brought to a juvenile home in Delhi, accused of killing a fellow student at a private school. They are from middle-class homes, with fathers in private sector jobs and mothers homemakers. “Based on what we know so far, it was a case of bullying or a trivial dispute taking a bad turn,” says the probationary officer at the home. “Four students got into an altercation in the school washroom, the victim was punched in the head, he died. No weapon was used, the three boys did not intend to kill. They are contrite now.”

Arguments or fights sometimes lead to violent revenge that goes wrong. Advocates Chhaya Khosa and Rachit Gupta, legal advisors to the juvenile justice board II, mention in a report how a spat between a class monitor and a student ended in the monitor’s death. A student who was scolded by a teacher on the monitor’s complaint went with his cousin, also a minor, to the monitor’s house and called him out. They beat him with a stick and he succumbed to his injuries. The offenders face charges of murder.

Sometimes it is teenagers’ misguided or misplaced sense of power, says a senior public prosecutor at a district court in Delhi. He has handled cases of juveniles being tried as adults for heinous crimes. “Most of them,” he says, “wanted to have influence, wanted their name to inspire fear. Some would want to be part of bigger gangs that were feared. They crave power.”

In such cases, says Khosa, family background can play a crucial role: if there are family members with a criminal record, it can warp a juvenile’s sense of right and wrong and lower the resistance to using violence or breaking the law. The father of a child whose case Khosa looked at was in judicial custody for the murder of his wife, the child’s mother. The child was declared in need of care and protection and spent a year at a juvenile institution before his maternal uncle and maternal grandmother took charge of him. “He was already disturbed to begin with, and a few bad elements made friends with him,” she says. “Soon he was stealing and committing other serious offences with them.”

“Antisocial peer groups can mean people living in a juvenile’s neighbourhood with whom he or she has come in contact,” says Gupta. “Often, they begin to enjoy petty crime committed in their company.” He mentions a juvenile held for attempt to murder. Within days of being bailed out, he was entangled in a robbery and murder case. It wasn’t committed for the money; it was for the thrill of operating with his gang.

Says Gupta, “There was a case in which a minor boy aged about 10 years committed theft of some jewellery at a wedding function. Later, it turned out that he worked for an organised gang that hires children from Rajgarh district of Madhya Pradesh. It is hard to crack these children to speak about the people who trafficked them to Delhi-NCR and trained them to commit such offences.”

Seasoned criminals often get juveniles hooked on drugs to compel them into a life of crime. “Drugs are an important link between juveniles and crime,” says Gupta. “Drugs of all kinds are easily available and it’s very easy for children to get the drugs, and it can be some kind of fun for them. Easy access to drugs is a huge problem in a city like Delhi.” He speaks of gangs that traffic children and train them for picking pockets, burglary and so on. The gangs support the children financially and legally. Quite often, they are chained to these gangs by their addiction.

There’s no focus on the suppliers, says Bharti Ali. “There is an organised mafia running it. It is a full-fledged business. However, no one wants to touch them because it’s a tougher call,” she says. “I interacted with a cop who told me he knew the people behind the drug mafia – including politicians – supplying drugs to a school but felt helpless in taking action. ‘I’m small fry against them,’ he said.”

***

Protecting children from a descent into crime is a different story altogether. Psychologists say juveniles in conflict with the law are shaped by their environment. “If they have stolen something, there would be a background to it. They have an understanding of how aggression needs to be expressed – they pick it from their environment. Moreover, there is no self-check, as it doesn’t exist in their environment,” says a psychologist who has counselled juveniles held for crimes.

Child rights experts say children brought to juvenile care are not given enough attention. They are just treated as cases. Reformation takes a back seat.

Child rights experts say children brought to juvenile care are not given enough attention. They are just treated as cases. Reformation takes a back seat.

Nicole Menezes of Leher, a voluntary group, speaks of a juvenile who has been shuttling between a care home and the juvenile justice board for seven years. He is addicted to marijuana and alcohol since childhood. “He works at a shop, and the day he gets his salary, he returns home intoxicated,” she says. “He’d steal when his body cried out for drugs. When we were called to handle him, he’d broken into a compound looking for a meter box to steal. When he was nabbed by cops, he’d get away by paying a bribe.”

She says that for a long time, no one was able to pinpoint the root cause of his problems. He’s 17-plus now and works at a furniture store, where his father has got him a job. “The clock is ticking for him,” she says. “There’s been no comprehensive assessment in seven years. If there had been a comprehensive assessment when he was nine or 10, he’d have been different.”

***

Experienced handlers of juveniles in crime say there isn’t enough money allocated for counselling and hence preventing juveniles committing crimes from carrying on into adulthood. “That’s why we need Nicoles,” says Nicole, referring to the role played by voluntary groups and individuals like her.

According to an analysis by HAQ, the share of budget for children has seen a decline since 2012-13. While this decline was steep and sharp in 2015-16, there has been little attempt to make up for it in the following years. In 2014-15, when the NDA came to power, the share of the budget allocated for children was only 4.52 percent. In 2018-19, in the last full-fledged budget of this term before the election, it has fallen to 3.24 percent. This despite the government adopting the National Plan of Action for Children in 2016, with specific goals and strategies to meet its commitment to India’s children.

The amount approved for child protection services from 2017-18 was Rs 1,083 crore. If you distribute it across 710 districts, it comes around Rs 1.5 crore per district! This amount goes into paying salaries and other administrative expenses. Little is left for those it’s meant for.

feedback@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the March 31, 2018 issue)