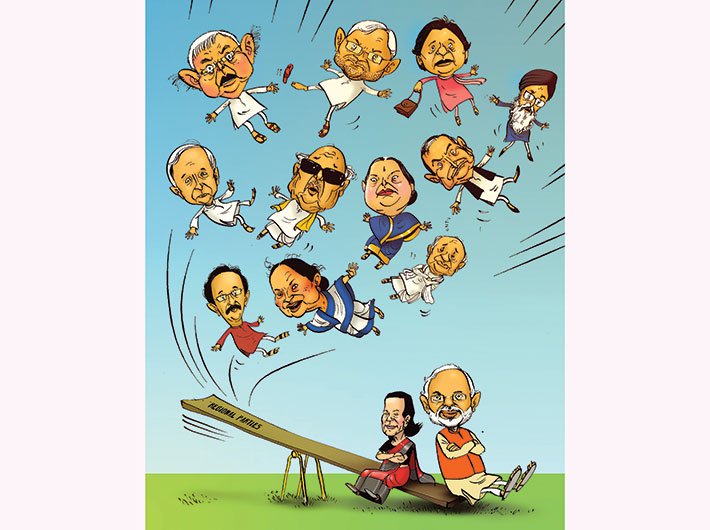

Regional parties have never had it so bad since their ascent beginning the early 1990s. The 2014 nadir is a wake-up call: regroup and re-strategise. Or is it game over?

The general election results are a wake-up call for all regional parties. Though it may be too early to think about the decline of these parties, the poll results indicate the need for a strategic rethink. Their future growth and continued relevance in national politics would require them to reimagine their role and strategy in Indian politics.

Since 1989, the importance of regional parties has consistently increased at the national level, so much so that they emerged as kingmakers. Between 1991 and 2009, for instance, the vote share of state parties increased by 15 percent, while that of national parties declined by 17 percent. Their seat share, too, increased from 51 to 146 in the same period while that of national parties dipped from 478 to 376. Until the results of 2014 elections, regional parties appeared to be indispensable in any process of government formation at the centre.

The elections this year upset this equation.

The changed scenario

Regional parties like Samajwadi Party (SP), Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), National Conference (NC), Janata Dal-United and the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) have been challenged by the BJP, which won 282 seats in the Lok Sabha – a gain of 166. It has emerged as a truly pan-India party with seats from states like Jammu and Kashmir, West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, where it was almost non-existent, while strengthening its position in other states.

In the crucial state of Uttar Pradesh, the BJP won 71 out of 80 seats. Dominant regional players like Mayawati’s BSP and Ajit Singh’s RLD failed to even open their accounts, while SP won only five seats, of which two were won by Mulayam Singh Yadav and one by his daughter-in-law Dimple Yadav.

The BSP had 21 MPs and the SP 23 in the 15th Lok Sabha.

In fact, alliance with the BJP has determined the fate of many regional players. In Bihar, the JD(U) sans the BJP won only two seats as against 22 last time, while Ram Vilas Paswan’s LJP won five seats in alliance with BJP. In Andhra Pradesh, the TDP’s alliance with BJP helped it win 16 seats, though there were other reasons too.

The post-election politics is an indication of things to come. Shiv Sena, the largest ally of BJP with 17 Lok Sabha MPs, could only whimper when it got a lone representation in the union cabinet in Ananth Geete. AIADMK leader J Jayalaithaa, a rival of BJP, did not rule out support to the Narendra Modi government in the Rajya Sabha “if the need arises”. More recently, she praised the centre for its “effective intervention” in the release of 53 Tamil Nadu fishermen from Sri Lanka. Both AIADMK and Biju Janata Dal (BJD), which did reasonably well in Odisha, have declared conditional support to the NDA.

Regional parties are being challenged in the states as well. In 1997, 15 out of 24 states were governed by regional parties. By 2014, 18 out of

28 states are governed by national parties. Although most states have a close competition between one of the state parties and a national party, with the swing in favour of either, the state parties appear to be in troubled waters of late.

Wasted mandate?

There can be little doubt that regional parties have contributed to the process of political mobilisation. However, the more important question is: has their contribution gone beyond mobilisation? Have they made any significant difference to the democratic (not electoral) politics? Have they ensured better representation, social justice or transformation? After all, mobilisation is a means to an end, and the end may range from better representation to social transformation.

Ideologically, most state parties are akin to the Congress. However, their distinctiveness lies not in one or other ‘ism’, but in the mobilisation strategy that they adopted. As is now common knowledge, state parties used caste, linguistic differences and a sense of deprivation to gain ground. They were able to organise hitherto underprivileged groups and convert them into major political forces.

Thus, the Mulayam-Mayawati duo organised and mobilised the ‘Bahujans’ into a formidable force in UP politics. Lalu Prasad consolidated the Yadavs and Muslims into a voice that had been ignored. The expectation was that they would facilitate a gradual transition from electoral democracy to substantive institutional democracy in terms of better representation of both ‘people’ and ‘their interest’.

Who are the representatives of regional parties? A study of Lok Sabha MPs carried out by the Centre for Public Policy, Bangalore, in 2004 and 2009 showed that there is little difference between the leadership of national and regional parties. A majority of the MPs are middle-aged, highly educated, agriculturists or political workers, and have fairly large asset base. State party representatives in Lok Sabha were no different. Sixty-one percent MPs of state parties were in the age group of 46 to 65; three-quarters of them either graduates or postgraduates. In fact, MPs of regional parties were found having slightly higher academic qualifications than their national party counterparts. The asset base of MPs of these parties is also as large.

These figures seem to suggest that their leadership continued to be elite.

What do they do? The legislative performance of regional parties – both in state legislatures and parliament – shows that their participation is similar to national parties. PRS Legislative Research shows that average attendance of MPs of state parties in 15th Lok Sabha was 69 percent – against 70 percent attendance of national parties’ MPs. Issues raised by them, too, were almost similar: demand for grants, infrastructure, better power supply and, occasionally, price rise and unemployment. Even the language, tone and tenor of debate were not substantially different. Most legislative time was spent by MPs in ‘trying to act like a representative’.

Alternative programmes? Regional parties have offered little to the electorate that is different in terms of policies. Interestingly, most state parties made little mention of national issues in their election manifestoes. Their positions on key issues like civil nuclear deal or FDI in retail is determined by politics rather than policies. Even at the state level, successful chief ministers from these parties have not adopted policies and programmes that are vastly different from that of the national parties.

For instance, there is very little to differentiate between the economic policies of the Nitish Kumar-led JD(U) in Bihar and Naveen Patnaik’s BJD in Odisha from that of Sheila Dikshit in Delhi.

Back to the drawing board

Given the significant dip in influence and import of the regional parties – over the last couple of years, though it was hastened by the 2014 Lok Sabha polls – and considering their role in widening the democratic ambit, there is an urgent need for them to re-strategise and provide true alternatives in policies, programmes and strategies. To begin with, these parties must develop independent national and state-level objectives and commensurate strategies.

Given the changing nature of electoral competition, the problem before regional parties would be to differentiate themselves from other parties – national- or state-level – based on concrete programmes. In India’s electoral system, where seats are won with a small margin, fragmentation of votes has resulted in some regional parties crowding out others. Take for instance the impact of the rise of Raj Thackeray’s MNS on cousin Uddhav’s Shiv Sena in Maharashtra, or PMK and MDMK on AIADMK in Tamil Nadu.

State parties have to be more ambitious in their approach with a broader vision for their party. Interestingly, leaders of regional parties with national aspirations – like Jayalalithaa and Lalu Prasad – have limited ambitions for their party and are often happy retaining their existing support base. Widening the party, particularly beyond their respective states, requires organisational thinking and is likely to bring in issues of devolution of authority, which regional leaders are not very comfortable with.

This may also be the reason why they have invested precious little in revamping the organisational structure of party.

These parties have apparently conceded their role as that of ‘influencers of the political processes’ – at least at the national level. They seldom seek or imagine a role for themselves beyond being kingmakers. This has limited their democratic potential. Perhaps regional parties have to develop constructive strategies, where they imagine themselves as alternatives and not also-rans.

With the decimation of Congress, regional parties have both the opportunity and the space to prove their credential as responsible critics of the government. Their future will depend on how well they perform this role. They would also do well to realise that new alternatives – like the Aam Aadmi Party – are waiting to fill the political vacuum, rather than just wishing it away.

Finally, regional parties have to build innovative strategy of mobilisation. The identity-based mobilisation that paid rich dividends has not been deepened to include more groups. If anything, it has been replaced by ‘mobilisation on the basis of development’ – definitely not an innovation. They appear to remain frozen in time and seem to have taken their electoral success for granted. In 2014 elections, for instance, there was only a half-hearted attempt at forming a united non-Congress, non-BJP front.

The success of India’s democracy is attributed to the mobilisation of the electorate. In part, regional parties were the architects of this process. In post-election politics the party system is likely to undergo a process of churning and regional parties may have to jostle for political space. In all likelihood, only those who further the process of democratisation to the institutional and policy level will survive.