Historical figures do not need our agreement, approval or sympathy. But we certainly need to understand how they went wrong and what they did right

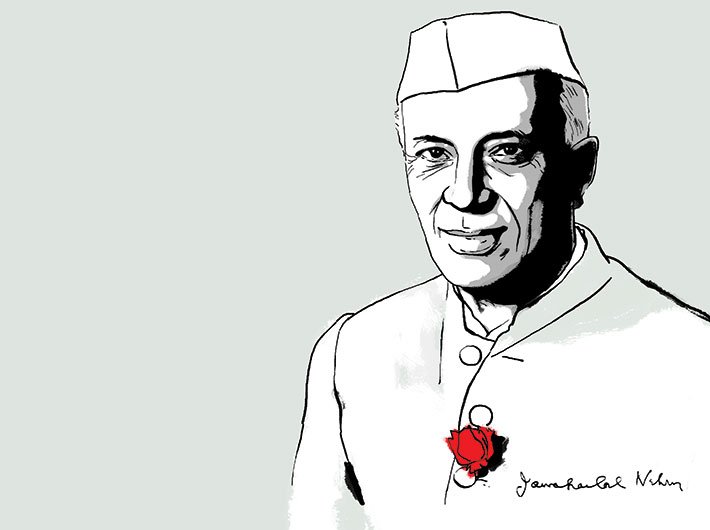

The ‘tryst with destiny’ was Jawaharlal Nehru’s first and most famous speech as prime minister. But the one that has most coloured his historical reputation came towards the end of his long innings. Speaking in parliament after the disastrous war with China, Nehru said: “We have been living in an unreal world of our own creation.” This speech was pounced upon by contemporaries as a confession of his naiveté and idealism. Scholars too have treated this as decisive proof that Nehru’s foreign policy was divorced from the realities of power politics. The defeat at the hands of China is seen as merely the nadir of a larger failure to secure India’s interests in the world.

In fact, Nehru’s mea culpa was aimed at soothing political tempers. In the wake of the China war, the prime minister had come under considerable criticism from the opposition and, more importantly, from within his own party. Even president Radhakrishnan had publicly chided the government for its “credulity and negligence”. Given the context, historians should have approached Nehru’s statement with scepticism. They should also be mindful of AJP Taylor’s observation that all politicians have selective memories – most of all those who originally practised as historians.

“The ambition of the greatest man of our generation has been to wipe every tear from every eye...”

Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom. A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long supressed, finds utterance. It is fitting that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of Inida and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.

At the dawn of history India started on her unending quest, and trackless centuries are filled with her striving and the grandeur of her success and her failures. Through good and ill fortune alike she has never lost sight of that quest or forgotten the ideals which gave her strength. We end today a period of ill fortune and India discovers herself again. The achievement we celebrate today is but a step, an opening of opportunity, to the greater triumphs and achievements that await us. Are we brave enough and wise enough to grasp this opportunity and accept the challenge of the future?

Freedom and power bring responsibility. The responsibility rests upon this Assembly, a sovereign body representing the sovereign people of India. Before the birth of freedom we have endured all the pains of labour and our hearts are heavy with the memory of this sorrow. Some of those pains continue even now. Nevertheless, the past is over and it is the future that beckons to us now.

That future is not one of ease or resting but of incessant striving so that we may fulfil the pledges we have so often taken and the one we shall take today. The service of India means the service of the millions who suffer. It means the ending of poverty and ignorance and disease and inequality of opportunity. The ambition of the greatest man of our generation has been to wipe every tear from every eye. That may be beyond us, but as long as there are tears and suffering, so long our work will not be over. And so we have to labour and to work, and work hard, to give reality to our dreams.

Excerpts from Jawaharlal Nehru’s speech

on 14-15 August, 1947

Nehru’s handling of foreign policy, including towards China, was hardly as naïve as his speech suggested and scholars have assumed. With the benefit of hindsight and access to documents, we can see a very different picture of Nehru’s engagement with the world. This is not to suggest that his foreign policy was hugely successful; merely that we need to see it in the context of its times and identify the right sources of the failures.

Let’s start with the much-maligned notion of non-alignment. This policy is held to have harmed India’s interests by steering it away from an alliance with the eventual winner of the Cold War – the United States – and by chaining it to the loser – the Soviet Union. This widely-held critique is wrong in assuming that Nehru had an ideological aversion to America or affinity to the Soviet Union. Non-alignment was a response to the international context in which India attained independence. In the recently concluded World War II, India had been forced to fight alongside the Allies without any reference to its own wishes. Nehru himself was staunchly opposed to the Axis powers, but India’s lack of choice certainly rankled. More importantly, it pointed to the problems of being a junior partner in any military alliance. At the same time, a new set of such alliances was taking shape with the onset of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union. Nehru was clear from the outset that India should be capable of judging its own interest in the emerging competition between the superpowers.

If anything, in the early years after independence, Nehru leaned more towards America and Britain. This was due to internal as well as external considerations. The Communist Party of India had denounced independence as sham and chosen the route of a revolution to overthrow the government. Its position naturally mirrored that of Stalinist Russia. In these circumstances, Nehru could hardly hope for a cosy relationship with Moscow. India’s external strategic interests also pulled it towards the Western world. Much of the military equipment held by the Indian armed forces was of American make – thanks to the Lend-Lease arrangement during World War II. So, India was dependent on the US for supplies and spares after independence. The extent of the dependence became clear during the first Kashmir war of 1947-48, when the US imposed an arms embargo on both India and Pakistan.

The experience of the Kashmir war, in turn, influenced India’s decision to remain in the British Commonwealth. This was a controversial decision, not least because it cut against the Congress party’s long-standing position on the matter. Yet, Nehru and his colleagues went ahead because it was perceived that a special relationship with Britain would serve as a counter-weight against excessive dependence on the United States. More generally, the Kashmir war underscored the importance of developing an indigenous defence and industrial base. Indeed, the foundations of India’s strategic autonomy were laid in the Nehru years.

India’s ties with the Soviet Union developed only after 1953. Two events spurred the relationship. First, there was a reorientation of Soviet policy towards newly independent countries like India after the advent of Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev. Second, the United States pulled Pakistan into a military alliance – a move that was rightly seen by Nehru as inimical to India’s interests. Then too, it is wrong to assume that India was closer to the Soviet Union. The United States remained the largest provider of economic assistance to India. Even the second five-year plan, which is seen as the epitome of the ‘socialistic’ approach of Nehru, owed more to American economists than Soviet ones. In strategic terms too, US-India relations were on the mend by the end of the 1950s. Throughout this period, the relationship with the Soviet Union was built on the consideration of India’s interests – not ideology. The decision to purchase the Mig-21 fighter planes – the beginning of the Indo-Russian strategic relationship – was taken because Moscow was willing to allow licensed-production of the aircraft in India. This was expected to bolster India’s own defence industrial base.

What about China? Nehru was certainly keen to establish a working relationship with communist China. With Japan lying prostrate after the war, China and India were the two major Asian powers. There was, of course, the United States. Nehru, however, felt that US policy of containing China would fail. More importantly, he believed that China’s own foreign policy was driven by its nationalism rather than the diktats of the Soviet Union. Indeed, Nehru was perhaps the first statesman to have foreseen the split between Moscow and Beijing. Owing to all these considerations, Nehru held that China should not be isolated from but socialised into the international system.

This did not, however, mean that Nehru was unmindful of the problematic aspects of India’s relations with China. As far back as 1954, soon after signing the Panchsheel agreement with China, Nehru wrote to a colleague, “In the final analysis, no country has any deep faith in the policies of another country, more especially in regard to a country that tends to expand.” In October 1959, following a stand-off with Chinese troops along the border, Nehru wrote that India had to face “a powerful country bent on spreading out to what they consider their old frontiers, and possibly beyond”.

Why, then, was India caught out by the Chinese attack four years later? Why did Nehru embark on a “forward policy” that sought to plant puny military posts on the border without backing them with an adequate defensive posture? The short answer is that Nehru and his colleagues believed that China would not engage in anything more than the kind of skirmishes that had already taken place. This belief stemmed from two sources. One, a Chinese attack on India would carry the risk of American intervention. Two, the Soviet Union would not back such an attack either.

Nehru’s assumptions were not off the mark. We now know that until the summer of 1962, the Chinese were indeed mindful of the risks involved in attacking India. Mao Zedong knew that the military balance strongly favoured China and yet thought that they could not “blindly” take on Indians. Yet, in a curious turn of events, they were assured by the Americans that they would not support any attack on China. A week before the war began, Khrushchev gave a nod-and-a-wink to China on the grounds of socialist solidarity – only to reverse his position swiftly. Nehru’s principal failure lay in his inability to anticipate these changes. They were not entirely unforeseeable, but nor were they easily predictable. Coupled with this was the military failure to backstop forward troops with adequate reinforcements.

As prime minister, the buck stopped with Nehru; even if other agencies, especially the Indian army, cannot be absolved of their failings in 1962. Yet, the defeat against China should not obscure other aspects of his foreign policy. Nor should the mere fact of the failure become an excuse for lazy condemnation. Historical figures do not need our agreement, approval or sympathy. But we certainly need to understand how they went wrong and what they did right.