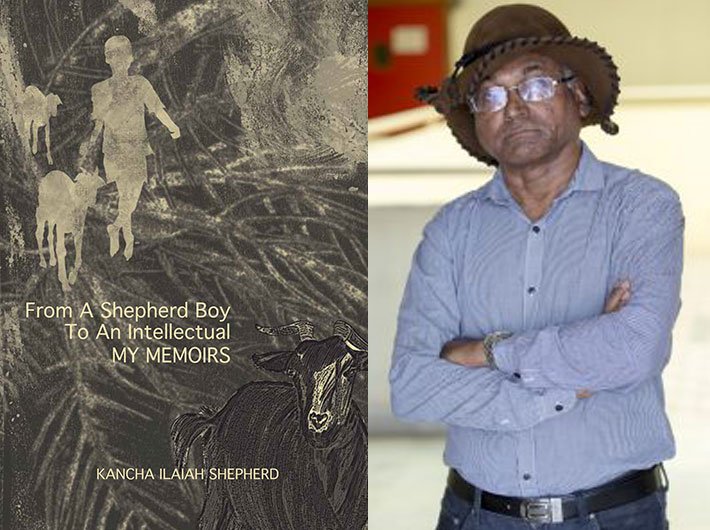

In his autobiography, Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd reminisces his college days and recalls the formative role of books

[Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, scholar and dalit activist, has penned his autobiography which is more than just the life-story of an individual but promises to become a document for a generation and a community. We reproduce below an excerpt, with the permission of the publishers, where he talks about his younger days and readings]

My reading in English of any book that I could get and practise by myself speaking English became a ‘lustful’ act. I had very cooperative roommates, who allowed me to do the dishwashing job early morning and sometimes in the evening too and be busy with my reading work. They used to cook food for me too. I used a simple principle to do that day-long job of reading–never in the nights. If I were unschooled I would have been with our sheep or goat or with agricultural work all day. Why not do that here too? My friends would do no work in the day, except attending classes, but read late in the night. I read quite a lot of books of the college library and also the regional library, which was just opposite the college at Subedari of Hanamkonda all through the day.

My method of speaking English came from two sources; one was my teachers. But some of them were very bad in communication. So emulating the good communicators was my mode. Second, the accent was picked up from the community radio news reading at 9 p.m. My resident room, for quite some time was just opposite the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Welfare Hostel. That hostel had a public radio. Listening to the English news every night was what I did conscientiously every day. Sometimes I used to bunk the class if the teacher was not very good; but not the listening to the evening English news.

Meanwhile, I began to enjoy political science, history and English literature, in that order. I used to dislike Telugu as a subject, which ceased to be there after B.A. second year. My disgust with Telugu was not because of the difficult letters or diction. Its fifty-six letters and other associated problems of sentence formation apart from the subject did not relate to any aspect of my environment. The books we were supposed to study in Telugu literature were from the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Prabhanda kavyas. Studying Telugu literature, however, seriously I learnt it, would confine me only to the Telugu region. I had already developed a universal mode of thinking and wanted to get into the IAS. I thought English literature was the best option and that would be a better way of fulfilling my mother’s dream. However, my love for English but not for Telugu was a peculiar one. At one level mine was a selection between a language that would expose me to universal knowledge and leave out a language that had only a local appeal. At another level my choice was between an unknown future and a known world around me. But I thought the Telugu texts that we were reading were not making much sense also, though it was a subjective feeling.

The so-called best Telugu text, which actually was a translation of Kalidas’ Sanskrit Meghasandesham (in Telugu Megha Sandeshamu) was not only difficult to read but it was around a silly subject of sending a message to a beloved through a cloud. There were texts written by Telugu Brahmin writers like Bommera Pothana, Viswanatha Satyanarayana but most of them would be around some mythological figures or around the Brahmin life, which always appeared meaningless and irrelevant to me. Slowly I was forming a persona. Learning English through The Communist Manifesto, though a translation, was far more relevant. It was talking about workers and exploiters. Their workers were proletariat but our workers were shepherds, farmers, labouring dalits, and so on.

Their exploiters were industrialists and our exploiters were feudal lords, Brahmins, Reddys, Velamas, and so on, and they were all around my life.

As a student of the European history I found out that there was a kind of similar feudalism in Europe. The only difference was that their feudal lords were class feudals who shared the same spiritual and social culture with their working class. The Brahmin feudals of India would have entirely different spiritual, social and even food cultural life. The Reddy feudals had the upper-caste arrogance, apart from their control though landed property. When the feudal class exploitation was compounded with caste hegemony the socio-economic controls got multiplied. If I were not a student of English literature and European history I would have not understood that there is a different world out there. For example, Wordsworth’s poetry was more interesting than any other Indian’s, particularly Telugu writers’ poetry, because I never found any description of nature—forests, animals, birds. Though Wordsworth wrote about the nature as existed in Europe I was familiar from my childhood of the nature of my area. But nature has some common narrative whether of Indian or European.

I liked Shakespeare’s Othello because the characters resembled many of our village characters. I had a sense of comparison. The sense of comparison with what is around made me what I was and what was being told in the book gives a sense of relationship to the text that one reads and the life one is leading. This was my strong point. And that led to my determination to move towards learning English in a rural setting where its day-to-day use was nil.

In a way Marx, other English writers like Wordsworth, taught me English and ‘Indianness’ because it was a question of mapping the description of those texts onto my own location, replacing words like capitalists with feudal lords or working class with working castes. I used to get pictures only of Indian exploitation while reading the European books. What the priest did after my mother’s death. How Epuri Laxma Reddy the Gudur landlord made us fall at his feet. How Narsimha Chary insulted me in class. I used to think whether the British Christian pastors do that to the churchgoers. The 1960s and 1970s were times of transition and some amount of self-respect was germinating among the lower castes of India. I was a product those times. Madhava Rao, a Dalit Collector, gave me an ambition and Marx, a German author, gave me a direction.

Excerpted from

‘From a Shepherd Boy to an Intellectual’

By Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd: Retired, Director, Centre for Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad.

2018 / 372 pages / Paperback: Rs 595 ( 9789381345412)/ SAGE Select Samya