You Must Know Your Constitution

By Fali S. Nariman

500 pages, Rs 799

Published by Hay House Publishers India

(Distributed by Penguin Random House India)

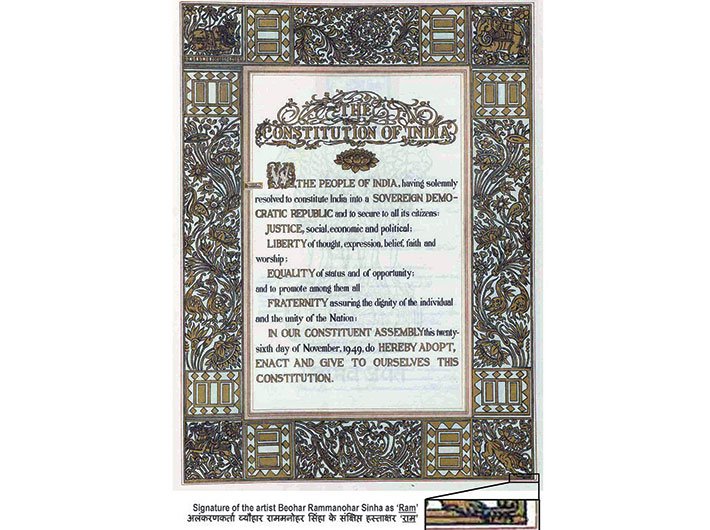

26 November 1949 marks the date when the longest constitution in the world was formally adopted to guide the largest democracy in the world. It effectively transformed the British Dominion of India into one nation―the independent Republic of India. The supreme law of the land set forth the workings of Indian democracy and polity, and its provisions aimed to secure justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity for the people of India. As drafted and as conceived, the constitution makes provision for a functioning democracy and not an electoral autocracy, and this is how it has to be worked. It is therefore imperative for all citizens to familiarise themselves with its provisions.

In this definitive work, renowned legal luminary Fali Nariman (who, incidentally, commenced his legal practice in the year the constitution was enacted) presents his comments in a style that is comprehensive, lucid, and systematic. The book traces the history and the origins of India’s document of governance and explains its provisions.

Here, the reader will find an educative and informative exposition of the different parts of the Constitution, including a bird’s-eye view of―and with comments on―all the 395 articles and additions made by constitutional amendments.

The book also provides references of critical cases and prominent constitutional developments up to July 2023. It insightfully describes the structure, powers, and directive principles of government institutions as well as updated judicial pronouncements and legislative and constitutional amendments.

In essence, You Must Know Your Constitution is an immensely readable and insightful compendium for judiciary aspirants, academicians, legal and administrative authorities, policymakers, research scholars, and students as well as for general readers who are interested in exploring the manifold facets of India’s core document of governance.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

‘EQUALITY of status and opportunity’ follows next in the Preamble—reflected in (and elaborated) by Articles 14 to 18 (as well as Article 29(2))60 in the Fundamental Rights Chapter (Part-III of the Constitution).

General

The principle of equality before the law is universally recognised. It has become an integral part of the constitutions of most of the civilised countries in the world. Peaslee’s classic work (in four volumes) mentions that nearly 75 per cent of the constitutions of the nation states in the world contain clauses about equality. The principle of equality is recognised as one of the fundamental principles of modern democracies, and governments based on the rule of law. In a book published in 1945 (then the first of its kind), Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, renowned jurist and president of the International Court of Justice wrote about the pre-eminence of equality in the governance of states:

“The claim to equality before the law is in a substantial sense the most fundamental of the rights of man. It occupies the first place in most written constitutions. It is the starting point of all other liberties.”

It is easy to be passionate about inequality which has increased dramatically in many parts of the world over the past two generations. Thomas Piketty, professor at the Paris School of Economics and co-director of the World Inequality Lab, has recently written about it in Capital in the 21st Century, with a shorter version published in 2021 titled, A Brief History of Equality (published by the Harvard University Press). In it (at pages 190-192), he has described ‘the case of India, which is the country that has gone the furthest in the use of quotas’ and has tentatively concluded: ‘If the balance-sheet on Indian quotas is on the whole positive, this experiment also illustrates the limits of such a policy . . .’

Though the principle of equality is universally recognised, its precise content is not clear.

Article 14

The first part of Article 14 of India’s Constitution (the State shall not deny to any person Equality before the Law) has been modelled on the concept of the Rule of Law and the second part (the equal protection of the laws) is a concept imported from the Constitution of the United States.

Article 14 has contributed a vast body of case-law:

The article had raised problems for the Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s. In State of West Bengal vs. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952) (AIR 1952 SC 123) (decision of a full court of seven judges when the strength of the court at the time was seven judges along with the Chief Justice of India), and in the companion case, Kathi Raning Rawat vs. State of Saurashtra (1952) (AIR 1952 SC 75) heard along with Anwar Ali Sarkar, a majority of the court (6:1) held that whilst Article 14 forbade class legislation, it did not forbid reasonable classification. But one of the judges— Justice Vivian Bose—did not agree. The classification test, he said, was not the only test. He then went on to expound his view that laws of liberty, of freedom, and of protection under the Constitution must be left to assume shape slowly as decision is added to decision. ‘They cannot be enunciated in static form by hidebound rules and arbitrarily applied standards or tests.’ However, Justice Bose’s ‘judicial-conscience test’ was a cry in the wilderness. His colleagues—and those who succeeded him— preferred the objective tests of reasonable classification, which in a later decision in Ram Krishna Dalmia vs. Shri Justice S. R. Tendolkar (AIR 1958 SC 538 (5J)) the tests were formalised in a series of six propositions. Since then it became a classic statement of the law on Article 14. There were several other cases as well. And by the end of the first two decades of the working of the Constitution, it was assumed that the problems raised by the Equality Clause had been judicially settled.

But a few years later came a concurring judgement of two justices in a bench of five justices in Royappa (1974) (AIR 1974 SC 555) where what is sometimes (disparagingly) called the ‘New Doctrine’ was first enunciated. This enunciation was by only two of the judges on the bench (Justice Bhagwati and Justice Krishna Iyer), who have left their mark on the decisions of the court. In Royappa, it was these two judges who expressed the ‘New Doctrine’ in the following terms:

(Quote) The basic principle which, therefore, informs both Articles 14 and 16 is equality and inhibition against discrimination. Now, what is the content and reach of this great equalising principle? It is a founding faith, to use the words of Bose, J., ‘a way of life’, and it must not be subjected to a narrow pedantic or lexicographic approach. We cannot countenance any attempt to truncate its all-embracing scope and meaning, for to do so would be to violate its activist magnitude. Equality is a dynamic concept with many aspects and dimensions and it cannot be ‘cribbed, cabined, and confined’ within traditional and doctrinaire limits. From a positivistic point of view, equality is antithetic to arbitrariness. In fact, equality and arbitrariness are sworn enemies; one belongs to the rule of law in a republic while the other, to the whim and caprice of an absolute monarch. Where an act is arbitrary, it is political logic and constitutional law and is therefore violative of Article 14, and if it affects any matter relating to public employment, it is also violative of Article 16. Articles 14 and 16 strike at arbitrariness in State action and ensure fairness and equality of treatment. (Unquote)

The excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.

‘You Must Know Your Constitution’ is published by Hay House Publishers India and distributed by Penguin Random House India.