Memoirs of the late administrator, known for his exceptional public service, leave the reader asking for more

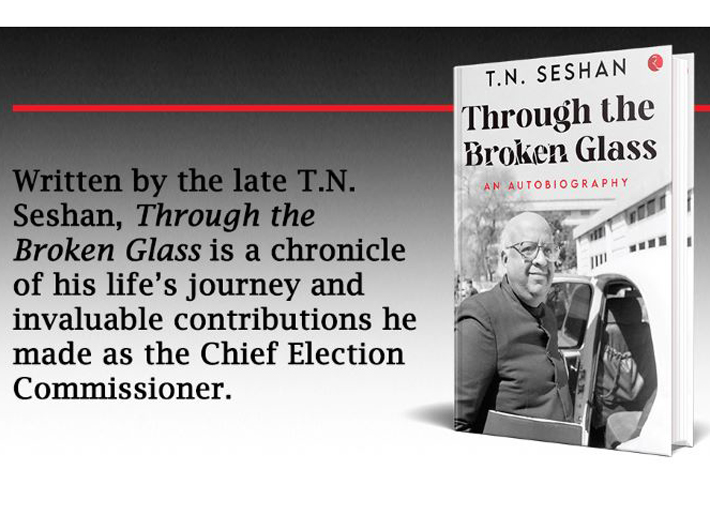

Through the Broken Glass: An Autobiography

By T.N. Seshan

Rupa, 368 pages, Rs 795

Tirunellai Narayana Iyer Seshan was a one-of-a-kind administrator. Nicknamed ‘Alsatian’ for his no-nonsense approach to what is arguably the most sensitive job in the nation, that of the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC), he is widely recogised as the man who raised the bar of integrity and excellence at the Election Commission of India (ECI) by several notches.

Before making headlines as CEC during 1991-1996 – quite a turbulent period in India politics, he had a nearly three-decade service as administrator in the IAS cadre, culminating with the post of cabinet secretary. When prime minister Rajiv Gandhi created a new ministry dedicated to environment, he had been the secretary there too. In recognition of his public service he was honoured with the Ramon Magsaysay award in 1996.

The sixth child of a lawyer father and a homemaker mother, Seshan was born in 1932 in Palghat, Kerala. As a student, he was brilliant at academics and went on to become an Indian Administrative Services (IAS) officer like his elder brother.

Seshan, at the pinnacle of his career, gained unrivalled popularity in India. Over six years as the CEC, he became a household name. Audiences and organizations across the nation were eager to hear him. Fan clubs were formed in his honour and to facilitate his work. His work found admirers across the seven seas, and post his retirement, he was even invited to the US president’s annual prayer event in early 1997.

His service at the Election Commission was tumultuous, but it was single-minded in the pursuit of free and fair elections. He was relentless in innovatively implementing codes through pre-existing laws and in bringing in new reforms, and, finally retiring in December 1996. It is in this last phase of six years that he made a huge and positive impact on the nation as a whole.

Before his death in 2019, he was at work giving finishing touches to this autobiography. Seshan penned two books based on his rich experience, ‘The Degeneration of India’ and ‘A Heart full of Burden’ (both in 1995).

Written with research assistance from Nixon Fernando, ‘Through the Broken Glass’ has a couple of chapters about his life before and after the service, and some also to his pre-ECI service. But, as he states in the Introduction, the trigger for writing this book was the suggestion of many friends who wanted him to “pen down my memories, especially my years spent at working as the CEC”.

Before Seshan came on the scene, the Election Commission was increasingly functioning as an appendage of the government. Over and above that, there was evidence that malpractice and lawlessness in elections were reaching alarming levels. If that trend were to continue then further down that track lay the ignominy of a ‘banana republic’ and the danger of Balkanisation.

Fearless to the core, in his autobiography, Through the Broken Glass, Seshan brings to light his years of struggles to usher in a new era of electoral reforms in India. Not the one to mince words and Seshan’s devil-may-care attitude and righteous self-awareness took even the Union governments by surprise. Written by a person who never cowered to the high and mighty, the book gives a no-holds-barred account of the man who revolutionised the electoral process.

Thought-provoking and inspiring to the core, ‘Through the Broken Glass’ is a testament to the grit and determination of the man who wagered a lone struggle to bring about a colossal change in the Indian electoral system.

This book was written when the author was well into his eighties. Setting the record straight about the numerous controversies during his tenure at the ECI might be his top priority. But there have been other controversies too, on which we would have liked to hear his final views.

For example, Seshan spends a few pages here talking about his post-retirement plans for public service and possible plunge in politics. But he refrains from recollecting two high-profile elections he fought – the 1997 presidential elections when he contested against the Congress-backed candidate, KR Narayanan and the 1999 general elections when he contested (as a Congress candidate) against BJP’s LK Advani from the prestigious Gandhinagar constituency.

His pioneering work at the environment ministry – he notes Rajiv Gandhi’s visionary concern about climate change – too could have been dealt in more detail. His opposition to the large dams, Tehri and Narmada (Sardar Sarovar project) in particular, is well known (not touched upon here). But then, his years at the nascent environment ministry should have merited a separate book.

‘Through the Broken Glass’, however, will remain indispensable reading on the working of the Election Commission and the all too important theme of electoral reforms.