Sitapati’s new book on Vajpayee-Advani partnership is also an invaluable guide to understand BJP, Hindu nationalism

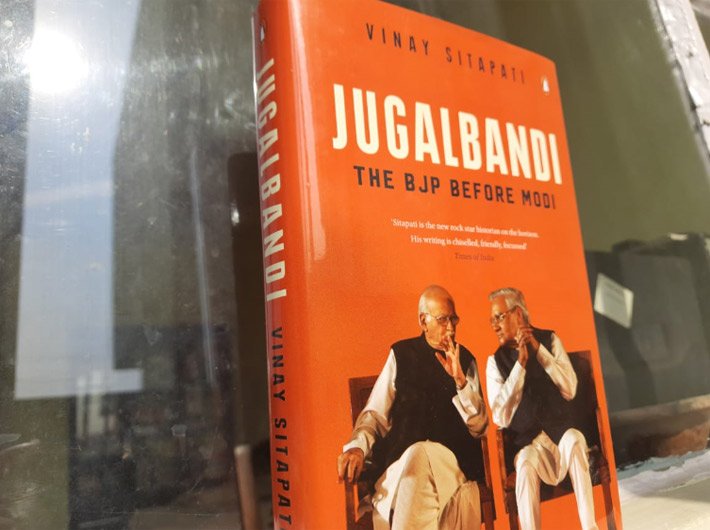

Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi

By Vinay Sitapati

Penguin Random House, xiv+410 pages, Rs 799

The love and respect India has for the first prime minister, Pandit Jawahlal Nehru, had largely remained undiminished for long decades, thanks to his role both in the freedom movement and in deepening the roots of democracy in the nascent republic. It was then surprising that the Hindu right-wing started targeting him for virulent attacks a few years ago. The Wikipedia page on Nehru was edited by some elements to alter his biography and add ludicrous misinformation. Much worse stuff continues to proliferate on social media. This is rather surprising, since in targeting the rival political party, digital warriors of Hindutva could have aimed better at Indira Gandhi (apart from the current face of the Congress, Rahul Gandhi). Why Nehru?

Vinay Sitapati’s marvellous new book, ‘Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi’, helps you make sense of many riddles like that one.

“Vajpayee and Advani came of age in the Delhi of the 1950s. It was a time in which the Nehruvian consensus was shared even by the non-Congress opposition,” he writes. In the aftermath of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination, the duo’s task was to make Hindutva acceptable to voters. “This context made them both realize that Hindu nationalism had to ‘moderate’ itself, i.e., reconcile itself to the mores of Nehruvian India. Even at the height of the rath yatra—with Hindus radicalized like never before—Advani pulled back from the edge. There was a line he would not cross.” Narendra Modi and Amit Shah, on the other hand, grew up in the 1970s Gujarat, and did not have to mould their politics in Nehruvian framework. If anything, they would succeed only by overthrowing that framework which had continued to guide the party. A reader can then conjecture that the attacks on Nehru were actually targeted at the “Nehruvian consensus”, signalling its end and the advent of a new grammar of politics. It can also explain the irrelevance of Advani, whom the BJP voter of today would find far less radical than himself or herself.

With his 2016 biography of PV Narasimha Rao, Sitapati (who was then completing his PhD from Princeton and now teaches at Ashoka University) had emerged as a leading chronicler of the contemporary politics. With ‘Jugalbandi’, he only raises expectations, as his narratives bring out the drama and colour, the odour of political lives. His works are of course informed by scholarly studies but eventually the former can enrich the latter more, rather than the other way round. (‘Jugalbandi’ has a small section at the end, titled ‘Scholarly contribution’ to mark out the author’s stand in relation to the growing academic literature on Hindu nationalism.)

Also read: But for Rao, India would be a different country today: Vinay Sitapati

‘Jugalbandi’ is, on the face of it, about the two inimitable leaders, their unique partnership (in which, the author underlines repeatedly, they swapped roles twice) and how it shaped what is now claimed to be the world’s largest party. In focusing on the duet, it does not ignore the chorus in the background, and thus becomes a partial portrait of India in the middle phase – between Nehru and Modi. Like a true history, it helps us understand the present – and make sense of the nation’s ruling party. Indeed, ‘Jugalbandi’, with its easy flowing narrative and rich anecdotes, is a better introductory guide to Hindu nationalism than several scholarly titles, as it deals with the human actors and how they put their ideology into practice while negotiating the vicissitudes of day-to-day democratic politics.

This has been achieved by the multitude of sources Sitapati has consulted: from archival news reports to interviews with scores of personalities who have witnessed the jugalbandi performance from close quarters. Many of the personalities that would first come to mind for this topic, however, seem to have refrained from sharing their insights.

There is one more lacuna that this otherwise excellent book will have to live with. Towards the end of ‘Jugalbandi’, Sitapati recounts a poignant vignette from Vajpayee’s last days. “One of the few people Vajpayee seemed to recognize was Advani, but one could not be sure. With both out of power, the warmth in the relationship seemed to have come back somewhat. Advani would visit once a month, and sit by Vajpayee’s bed. He would be silent. They would be silent. And then he would leave.” Over the more-than-half-century-long relationship, like any old couple, they too must have reached a stage where words are superfluous. Silence too can make music – in this case, a rare jugalbandi. What they communicated without words is bound to remain beyond words.