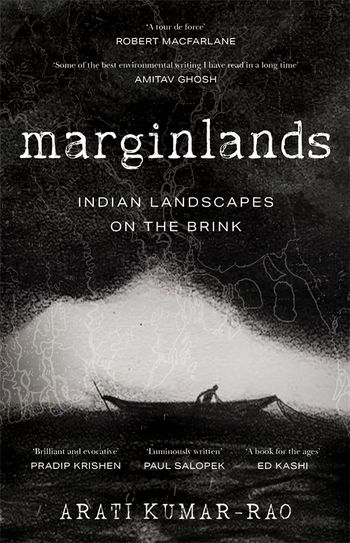

Arati Kumar-Rao’s collection of reportage is essential reading – and a model of nature writing

Marginlands: Indian Landscape on the Brink

By Arati Kumari-Rao

Picador India, 256 pages, Rs 699

This monsoon, Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand witnessed heavy floods. The deluge swept away whole buildings on the riverbanks. As people tried to overcome the shock and get back to life, there was another round of the same, and then once again, in Himachal Pradesh. Delhi has one of the country’s biggest rivers passing through it but depends on Himachal for its water supply, and the floods left a scare even in the national capital.

Around the same time, several places in the West were breaking heat records, or facing floods or wildfires, for the second or third time in the last five years. A week ago, there was an earthquake in Morocco, followed by floods in Libya.

We are, in other words, living in apocalyptic times. Climate change is leading to an increase in extreme weather events (though not every event is necessarily prompted by global warming). We are possibly past the point where effects of industrialisation could have been reversed, and yet India and China – two of the three biggest polluters – have plans to set up coal-based power plants.

Those who believe climate action is not just the biggest issue – bigger than varieties of identities and nationalisms and so on, but an issue of the very existence of humankind are in minority. For some reason, terms like ‘carbon footprint’ and ‘endangered species’ don’t have the same emotive appeal as ‘sanatan dharma’ and ‘Pakistan’. Mother Nature is not as hot-button an issue as Mother Cow is. Green parties have not made a mark in the West either.

What is to be done? Among other things, the facts of the matter can be made to appeal to emotions. Stories can touch more hearts. Stories of destruction, stories of rejuvenation. Leading American novelist Jonathan Franzen, who has also written about nature, puts the same point differently in a New Yorker essay in which he diagnoses “The Problem of Nature Writing”. To succeed—to get people to care about preserving the world—it can't be only about nature, he writes.

Arati Kumari-Rao realised that truth quite some time ago, when she quit her well-paying corporate job and ventured into “the uncertain world of environmental storytelling”. Her stories – stories of lands, stories of men and women who lived with nature – appeared on various platforms. She researched, went to the field for reporting, met people, wrote and also shot. (The book reproduces a few of the photographs, along with evocative sketches.)

‘Marginlands’ is her first book. It has five parts, focusing on The Desert (how Thar manages water), Veins of Our Land (about the Farakka Folly), An Eroding Margin (on the Sundarbans), The Third Pole (about creative attempts to engineer glaciers in Ladakh) and The Sound of Cities.

One indication of Kumari-Rao’s approach to the subject is reflected in the endnotes. That section is quite thin, and then again mostly referring to environmental essayists and poets like Wendell Berry and Barry Lopez. Instead of picking up research and turning an interesting finding into a field story, she has preferred to go to places, spend long months there, live with people who have lived with nature and learn from them how to decipher the changes in it. ‘Marginlands’, thus, harnesses deep, lived wisdom of people who still consider themselves part of nature and not masters of it. Since they form an endangered tribe, with their next generation moving to cities for more secure livelihoods, this wisdom and its vocabulary is disappearing right before our eyes. The ‘Desert’ section, for example, is a tribute to that traditional knowledge – a theme first explored by the inimitable Anupam Mishra.

Elsewhere, she recounts chronicles of disasters foretold, and the suffering of people due to well-intentioned but misguided reliance on ‘engineering’ solutions – precisely what many hope will see us through climate change.

It has been said for Tolstoy that if the world could write itself, it would write like Tolstoy. No comparison, of course, but if nature could tell stories, it would do so somewhat like many of the people in this book do. Kumari-Rao’s well-written reportage is an essential reading and a model for nature writing.