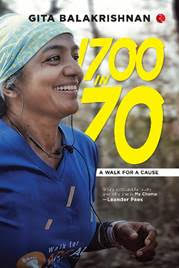

An excerpt from Gita Balakrishnan’s quest to discover India on foot – 1,700 km in 70 days, and explore design sensibilities intrinsic to the fabric of Indian society

1700 in 70: A Walk for a Cause

By Gita Balakrishnan

Rupa Publications, Rs 595, 208 pages

At fifty-three, Gita Balakrishnan, an architect by profession, set out to discover India on foot. Her main aim for going on this journey was to explore design sensibilities intrinsic to the fabric of Indian society and initiate a dialogue on design literacy.

At fifty-three, Gita Balakrishnan, an architect by profession, set out to discover India on foot. Her main aim for going on this journey was to explore design sensibilities intrinsic to the fabric of Indian society and initiate a dialogue on design literacy.

The result is ‘1700 in 70’, which documents her inspiring story of determination, resilience, physical endurance and spiritual growth against the backdrop of India’s diverse landscapes, cultures and architectural heritage.

While traversing 1,700 km in 70 days, from Kolkata to Delhi through cities, towns and rural heartlands, the author highlights the crucial role of design in every facet of our lives. The author engages with local communities, immerses herself in their cultures and finds inspiration from their use of traditional construction practices. In this inspiring book, she delves into the power of design—from creating dwellings and shaping lifestyles to building communities and forging identities.

‘1700 in 70’ is a captivating narrative full of compelling accounts. It urges you to slow down and find purpose in your individual journey.

Here is an excerpt from this book:

The Women of My Country: The Other Half?

The female population in our country in 2020 was 662.9 million against the male population of 717 million. Observing women and drawing inferences from my daily interactions about their position in society became an important pursuit for me on the 1700. I was not looking at producing a factual research paper but was instead getting a first-hand perspective on women’s place in society. Interestingly, these observations threw up insights on a lot of other fronts too. Women hold varied positions—while they seem to wield a lot of influence in determining choices that families make, they are marginalized when making critical choices in their own lives. For instance, they do have a say in the kind of home they would be building, where the kitchen and the toilet should be, the number of rooms, the sizes of the rooms and even financial planning, but they lose their voice when decisions on their daughter’s education, marriage or their own desire to start a business or begin a vocation is in question. There are unsaid norms and rules that are in play all the time that not many dare to confront.

On construction sites, people were surprised when I asked why women were paid lower rates. No one had a response, but no one expected the question either. There were many worksites where there were no women in the construction workforce. I was consoled by friends in Jamshedpur who knew of contractors ensuring parity as they found great value in the sincerity of the women on their sites. I was also happy to hear the verdict that better well-being was ensured on sites where men and women worked together. Women architects too are more likely to be accepted on sites where there are construction workers from both sexes and gender parity is practised.

I saw women on their way to work in fields and construction sites—taking healthcare to doorsteps, running errands, handling shops and much more. I came across many instances of sisterhood through simple actions. A woman rushed to help me thinking I was injured when I sank to the floor in exhaustion. There were many women who wanted me to look at their homes and to have tea with them. One old woman casually asked me to help her with a load of firewood that she was trying to lift onto her back. While it was certainly a photo opportunity that we missed, it is so cleanly etched in my mind. She did not think twice before asking me—almost as if I belonged. I bonded with women around a well; as they were drawing water, they spoke of their miseries about not having a water source near their homes.

There were women who walked together to a neighbouring village to work in the fields and were paid for their labour in the form of the grains harvested from the farms. It was lovely to see them, a group of colourful ladies sitting on the side of the road, chatting happily after having a breakfast that they had brought from their homes. They were waiting for 9 a.m. when they would start toiling in the fields.

They did not think they were being exploited by not being paid any wages. What they got in return for their hard work helped them tide through the period when there was no work on the farms.

The transformation in habits and behaviours across different states and even within regions of the same state was quite drastic. Women in West Bengal and Jharkhand appeared less inhibited; they rode bicycles as a common mode of transport. I even saw a few women carrying men as their pillion riders. Young girls in trousers were not an uncommon sight in the rural areas of these states. While women in most parts of West Bengal were very friendly, I saw a certain reticence in their demeanour as we reached Purulia, possibly reflecting the stress owing to the impending elections. I felt an infectious vibrancy in the young girls in Jharkhand and hoped that they would be able to retain it throughout their lives. Women were garrulous in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, but some of them were camera-shy. The ghungat (veil) was a regular feature I noticed once I left Jharkhand behind. In Madhya Pradesh, an old lady refused to believe that I was walking this whole distance. I gave up trying to convince her that it was true and humoured her.

The girls I walked with at Madla in the Panna district of Madhya Pradesh were special; they had an answer for every question and a question for every answer. While they excitedly told me about their future plans, I heard a young man sniggering in the background. He said, ‘All their future plans will be decided by their better halves.’ While his comment echoed reality, I hoped that seeing me venture out had given them some courage to prove the man wrong.

[…] Women are planners, doers and leaders, all in one, and so transformation in our country is being led by women. Many government schemes, whether it is the ‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’, ‘Kanyashree’ or ‘Ujjwala’, have certainly helped change the lives of quite a few women. These women have, in turn, influenced many more to take decisive steps in improving their own lives and consequently the lives of those around them. I have heard about Ganga Ahirwar, a woman from the Muhalpur village of Guna district, who used the Ajeevika Mission to better her own life and that of her family. She then went on to start the Uma Self-Help Group with eleven women to further the impact. There are many such Gangas in our country making waves quietly. They may be unsung heroes but their voices are loud hymns of change.

[The excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers]