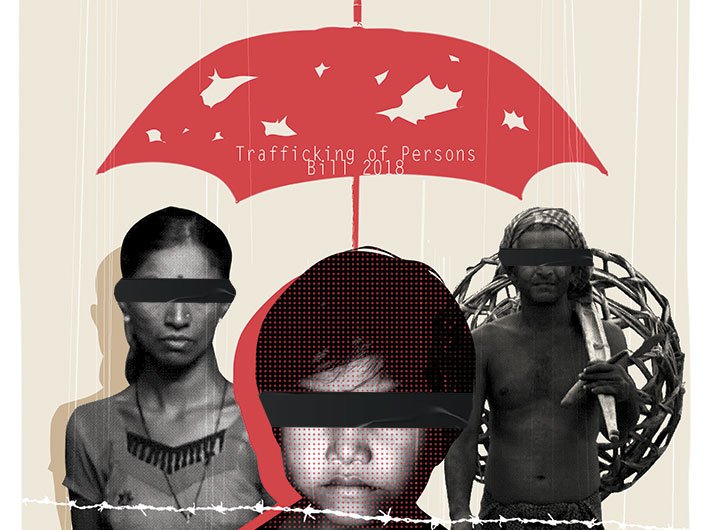

In July, the Lok Sabha passed the Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill, 2018. This umbrella legislation aims to combat all forms of trafficking, whatever the purpose. Minister for women and child development Maneka Gandhi calls it a stringent, comprehensive bill, focussed on rehabilitation of victims. She says it is not intended to harass sex-workers or other victims of trafficking. But the bill has evoked a groundswell of criticism.

First, critics say all that the new law does is create some new institutions: a national anti-trafficking bureau; district-level units and committees; special courts. In addition, it makes punishment more stringent, and questionably includes some ancillary acts – such as allowing a house to be used for trafficking – in the scope of punishable acts. Second, they say it draws on several existing laws for prosecution and penalty, so what is new other than making the penalties and jail terms more severe? Third, the deepest and most trenchant criticism is that the new law does not go into the complexities and several gradations of the trafficking problem. A person trafficked for organ harvesting or as cheap labour, for example, needs to be helped and rehabilitated in other ways than someone trafficked for sex work. There are matters of intra-national and international migration, people smuggling, the economics of labour, agricultural failure, poverty, corrupt police and other law enforcers...the list of factors related to trafficking could go on. Serious ethical questions, such as that of whether prostitution or sale of an organ is out-and-out illegal; questions of choice, such as whether an adult engaged in prostitution wants to be rehabilitated in the manner the state chooses – these go unaddressed, as if they are of no consequence or have been decided with utter finality.

Swati Maliwal, chairperson, Delhi Commission for Women

Swati Maliwal, chairperson, Delhi Commission for Women“The new bill is one step foward. It’s not a bad bill and we support it. The bill proposes attachment and forfeiture of property used for trafficking, which is a great step. However, the main focus should be on implementation. The bill underestimates the role of state commissions for women and doesn’t give them the power to act. It gives more power to anti-human trafficking units (AHTUs). The new bill divides responsibilities between the centre, the state, and district authorities, with AHTUs answerable to both the centre and the state. Actually, more power should be given to the police and the police should be held accountable.

At least the bill talks about rehabilitation, in fact about a holistic and multi-pronged approach to rehabilitation, including economic, psychological and social, which is appreciated. But the government must ensure that victims’ identity never gets revealed. In courts, when required, the government protects the identities of victims, so why not in these cases?

Prostitution is the worst kind of slavery. Will those who support legalisation of prostitution allow their daughters to get into the business? I cannot. And even a sex worker doesn’t want her child to become a sex worker. Women are forced into prostitution. No one chooses prostitution.

A lot needs to be done about our shelter homes, which must be strictly monitored. It’s the government’s job to make sure that victims feel safe at shelter homes. Rescued sex workers often say there’s no difference between live at GB Road (a red-light area in Delhi) and shelter homes.”

Nisha Gulur, activist, member National Network of Sex Workers

Nisha Gulur, activist, member National Network of Sex Workers“Over the past seven months, the National Network of Sex Workers held extensive consultations on the bill with sex workers and transgenders from across eight states. Even before the bill was passed in the Lok Sabha, we requested all MPs to send the bill to the standing committee. We want a discussion with the government and policymakers.

The proposed bill does not account for the consent of the person at the receiving end of its rescue and rehabilitation model. The law gives more power to anti-human trafficking units (AHTUs) to decide about the lives of sex workers picked up in raids. They will be deciding on behalf of the victims. That would be final and not open to appeal in courts.

The bill forces us (sex workers and transgenders) to be repatriated home. I am transgender, I found my support system here in this big town. No one can tag us as immoral and decide on our future on where we should live.”

Tripti Tandon, deputy director, Lawyers Collective

Tripti Tandon, deputy director, Lawyers Collective“The rescue and rehabilitation provisions in the bill are outdated. The bill falls back on outmoded methods of rescuing and detaining victims in the name of rehabilitation. Protection homes and rehabilitation homes remain the mainstay of rehabilitation under the anti-trafficking bill even though institutionalisation of victims in homes, ostensibly for their protection and rehabilitation, is antithetical to fundamental rights and re-integration.

The new bill is in interplay with existing laws. The last legislation defines trafficking under Indian Penal Code (IPC) sections 370 and 370A. Section 371 of the penal code criminalises slavery. Sections 372 and 373 of the penal code criminalise buying and selling of underage girls for prostitution. We already have the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, 1956, which criminalises activities related to prostitution and provides rescue, rehabilitation and correction of sex workers, albeit through a moral lens. The Juvenile Justice Act, 2015, provides a framework for protection of children who are missing or at risk of being trafficked. The Bonded Labour System Act, the Contract Labour Act, 1970, the Inter-state Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979, Children (Pledging of Labour) Act, 1933, and the Child Labour (Regulation and Prohibition) Act, 1986, which deal with forced labour, child labour, primarily through regulation and welfare-oriented measures.

The government has not abolished these Acts, but is creating a new law. The new bill fails to define trans sex workers and sex workers, creating more hassles for victims. In such a scenario, it only creates more and more confusion for police and the legal system. It creates extra paperwork for the administration. Much of what is proposed already existed in the law. The bill, in the name of rehabilitation, is only imposing surveillance and restricts victims’ freedom.”

Amod K Kanth, former IPS officer, founder of Prayas, an NGO

Amod K Kanth, former IPS officer, founder of Prayas, an NGO“The new bill brings in accountability of agencies in matters of rehabilitation. It’s not only the victim who will benefit from the new law, but the entire justice delivery mechanism. The Section 370 amendment (to the Indian Penal Code) defined human trafficking, but many ascpects remained uncovered. In the previous law, it was the duty of the police to rescue the victims and there was no accountability of the agencies in providing rehabilitation.

As for legalising prostitution, no woman voluntarily chooses to be a sex worker. Do you know any woman who willingly chooses to be a sex worker? Women in dire need of money will choose to be sex workers. We are in the bigger fight to save the country’s children and women. Victims are grappling with problems, including poor health, poverty, depression and lack of awareness about their rights and future. And this bill offers rescue, rehabilitation, time-bound trial of accused and repatriation of the victims. The bill provides for confidentiality of victims, witnesses and complainants. This bill offers hope for victims’ future so that nobody can push them to be sex workers.”

Arunendra Pandey, of Arz, a Goa-based NGO working to rehabilitate sex workers

Arunendra Pandey, of Arz, a Goa-based NGO working to rehabilitate sex workers“The bill fails on rehabilitation and creation of alternative livelihoods. It talks about shelter-based rehabilitation in two kinds of homes – protection homes and rehabilitation homes. However, both are generally rejected by victims of commercial sexual exploitation. These homes can be fine as temporary shelters but not in the long run. What we have been demanding is community-based, non-shelter home-based rehabilitation.

My 15 years’ experience says that many of these women, when they come out, do not want to be caged. Their freedom is curtailed in the name of being provided services. They want to live a life like you and me, with freedom. We need to talk about their livelihood separately. The government fails to do this. Moreover, the bill fails to give protection to victims. All these reasons could result in re-trafficking. Eighty percent of the rescued women want to come out from the dark world of trafficking, but we need better rehabilitation measures and alternatives.

The government cannot rehabilitate a bonded labourer in the same manner as someone who has been sexually exploited. Are they going to give the same kind of services to all victims? The kind of abuse victims received is different. They cannot be treated in the same manner. Both need a different kind of counselling and emotional support. The bill is fine on paper, but it lacks the moral will.

Instead of introducing this bill in the present form in the Rajya Sabha, it should be sent to the parliament select committee for further discussion.”

Ranjana Kumari, director, Centre for Social Research

Ranjana Kumari, director, Centre for Social Research“The bill introduces rehabilitation as victims’ right. It is a very positive step, and I appreciate it. So far neither rehabilitation nor prevention or protection has been introduced by any government. This bill gives teeth for protection and prevention legislature.

But I do not agree with the idea of community-based shelter homes. Let the shelter homes be the responsibility of the centre or state governments, not some NGO. Community-based shelter homes run with political connections and lead to incidents like those in Muzaffarpur and Deoria.”

PM Nair, chair professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

PM Nair, chair professor, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai“This bill with a zero-tolerance motto is a bold step. It’s for the first time that a bill or legislation makes relief and rehabilitation of the rescued person a matter of right. The bill makes it clear that rehabilitation is not contingent on the prosecution. There would not be any pressure on the victim to speak for the state or depose in any particular manner. The bill brings in accountability of the rehabilitation agencies of the government. Under the existing laws, a duty was cast upon the police to rescue and, yet no accountability existed on the agencies of the government regarding rehabilitation.

The bill has given a specific character, shape and method to the rehabilitation process. The functions and roles of middle agencies have been delineated. The creation of national, state and district level committees on rehabilitation provides a single-window approach to the entire process.

The freezing and confiscation of illicit assets born of trafficking crimes is indeed an important and landmark addition to the anti-trafficking law. Neither section 370 IPC or ITPA has any such provision. It is well known that traffickers make huge profits out of the sale and purchase of human beings.”

Roop Sen, activist, founder of Sanjog

Roop Sen, activist, founder of Sanjog“The current approach to rehabilitate victims of sex trafficking is to institutionalise them in closed institutions, which the NGOs call shelter homes. But for survivors, the vocational training does not lead to employment and takes away vital years of childhood and youth from them. What is required in the context is for services to be provided to them once they return to their families and communities. That is where they need anti-poverty services, legal services, health services and social workers’ assistance to ensure that families and communities do not stigmatise them. The new bill defines rehabilitation and makes the state commit to services to be provided for victims’ recovery and rehabilitation, both economic and social. The district magistrate is named as the responsible authority to ensure rehabilitation and prevention. This can help in mainstreaming services through panchayats, rural health care centres and hospitals, and block development offices instead of funnelling services through the social welfare department and NGOs. All of these granular issues and processes will need to be illustrated when states draw up implementation rules.”

deexa@governancenow.com

(The article appears in September 15, 2018 edition)