Authorities failed to use MGNREGA and NFSA provisions meant for relief in difficult times, forcing the supreme court to intervene

For the past two months Ghaneshwar Yadav, a native of Bihar, has been working as a daily wage labourer in New Delhi’s Okhla area. With a few clothes tucked into a tattered plastic bag, Yadav came to Delhi after his crop failed this year due to drought. “Gehun ka daana tak nahi phoota is baar. Puri khadi fasal khatam ho gayi (There was no yield this year. The standing crop got damaged due to water scarcity),” lamented Yadav, a fair-complexioned man in his thirties.

Clad in black pants folded till his knees and a brown shirt drenched in sweat, Yadav tells Governance Now: “We haven’t earned anything from farming this year. I am here to earn money for my family.”

His worry is palpable, for he left his family alone in tough times. “At least I earn Rs 200-500 a day by shifting load from one place to another. In a month I am able to save a few pennies and send it to my family,” he says with a shrug.

Many parts of India have suffered from continued drought or water scarcity during the last two years, leading to crop failures and mounting loan debt. More and more people are forced to migrate out of rural areas.

Social security measures like Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and National Food Security Act (NFSA) have apparently not been effective enough to help stall migration.

Currently, 11 states are in the grip of drought which has affected 33 million people – close to a third of the population.

There are media reports of mass migration in north Karnataka. In Telangana, cases have been cited from Mahbubnagar district. Maharashtra’s drought-hit Marathwada region has seen mass exodus to Mumbai and Surat. From Jharkhand, people are heading to Kerala.

The severely affected villages in Bundelkhand, a central region divided between the states of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, is mostly left with women, children and aged men, said Swaraj Abhiyan founder Yogendra Yadav, who completed his 11-day-long padyatra through Marathwada and Bundelkhand on May 30.

“In villages, if you ask for an able-bodied man, 60 to 80 percent of them have migrated to urban areas to earn their livelihood. They are migrating to Delhi, Faridabad, Gurgaon, Indore and Surat. You meet elderly, children and women, but you don’t meet able-bodied men in the village. It’s an entirely migrant-dependent economy right now,” Yadav told Governance Now.

The acute distress due to crop failure in the last three years in Bundelkhand and Marathwada has either led to mass exodus or suicides. At least 216 farmers have committed suicides in Maharashtra alone.

Due to uneven and inadequate rainfall, many states witnessed a dry spell in the months of cultivation which led to huge farm losses. The yields reduced substantially in several areas due to lack of soil moisture. The investments made by farmers in terms of labour, seeds and other inputs did not give proportionate income, leading to financial distress.

According to an affidavit submitted by Jharkhand in the supreme court in a drought-related case, more than 50 percent crops had failed in the state by November 2015. The expected crop yield of the state was 74.71 lakh metric tonne which is now expected to be 65 lakh metric tonne due to scanty rainfall.

The situation is no different in Bundelkhand. “Farmers in the region lost six crops in last three years. The luckiest farmer has lost four crops while the unlucky one has lost all six,” said Yadav.

The only option left for the vulnerable populace is to migrate. Early June, hundreds of farmers from Bundelkhand huddled under a flyover outside Delhi’s Hazrat Nizamuddin railway station.

The Indian Express quoted a Delhi government spokesperson as saying that there are no specific records of farmers migrating from Bundelkhand because of the informal nature of their travel and work. “We have been getting reports of farmers taking trains to Delhi. It is difficult to keep count because so many people reach Delhi from all over the country. Many of these farmers travel to other parts of NCR as well,” the spokesperson said.

The 2001 census placed the all-India figure of migrants at 307 million.

“There is no systematic study on migration so far,” said professor Ravi Srivastava, Centre for the Study of Regional Development, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). “In a drought- or famine-like situation, migration is the only coping mechanism. Drought has led to a spurt in distress migration as cases of exodus are reported from drought affected regions.

“Currently, there is a decline in foodgrain production in the drought-affected states. Even prices of agricultural commodities are low. The agriculture sector is in the most severe state. Therefore, the vulnerable population prefers to migrate to earn basic livelihood,” said professor Srivastava.

KS James, a professor at Population Research Centre, Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru, said, “The migrant population of India must have increased by 20-30 percent now from the 2001 census figures. The overall figure must be 350-400 million.”

On migration in Karnataka due to drought, James said, “Drought does not restrict itself to water scarcity. It adversely affects rural population by making them unemployed. Employment opportunities related to agriculture sector or animal husbandry drastically comes down. The mode of earning livelihood gets finished. Therefore, distress migration increases. In such a scenario effective implementation of MGNREGA becomes crucial.”

Distress migration and MGNREGA

MGNREGA is a safety net to reduce migration by poor rural households in the lean agricultural period. It is intended to reduce labour mobility by providing unskilled work.

Highlighting the achievements of UPA’s flagship scheme of rural employment, in 2010, then labour minister Mallikarjun Kharge told the Rajya Sabha that MGNREGA helped in reducing the number of migrant labourers in the country as employment was being provided to them in their own villages.

But the scheme that guarantees 100 days of employment is now grappling with fund crunch, delays in wage payments and violation of workers’ rights and entitlements, leading to less efficacy.

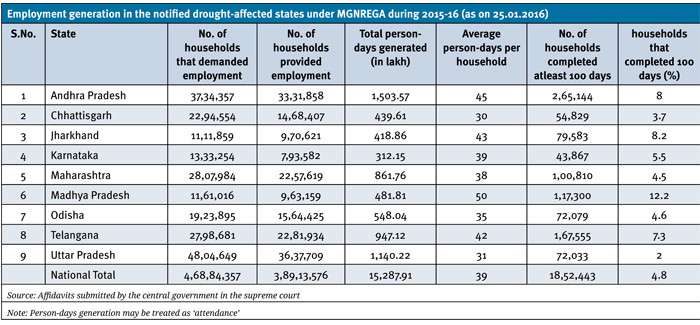

The supreme court on May 11 and May 13 pulled up the central and the state governments for poor implementation of MGNREGA and NFSA after a public interest petition was filed by Swaraj Abhiyan late last year against the backdrop of a declaration of drought in some districts or parts in nine states then – Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra, Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Moreover, the petitioner had then said drought ought to be declared in parts of Gujarat, Bihar and Haryana and essential relief and compensation be provided to the affected people.

The apex court in its order asked the centre to provide adequate financial resources to state governments for MGNREGA and payment of all pending wage liabilities along with compensation for the delay in wages.

Yogendra Yadav claimed that the Madhya Pradesh government seemed blissfully unaware of its legal obligation to comply with the law and the directions of the apex court.

“Virtually no MGNREGA work is happening and less than 30 percent of the state’s own targets have been achieved. No effort to use MGNREGA to offer employment to the impoverished was visible,” he said.

“Bundelkhand region in Uttar Pradesh, especially Mahoba district, was the only place where MGNREGA was visibly being used for drought relief. This part of UP has exceeded its target of man-days employment for April-May,” he added.

In Bundelkhand, a young boy pushes a wooden pulley for drilling purpose to access groundwater

According to him, in most of the villages they visited during the padyatra, almost nobody possessed job cards or received any payments. “It was in sharp contrast with official statistics, which show a large number of job cards in those villages. It is quite evident that this scheme has been captured by the locals who wield power and bureaucrats to siphon off money meant for drought relief,” he claimed.

Initially there was a budget cap on the MGNREGA funds. In 2014-15, the initial allocation was of Rs 34,000 crore. So, by the end of the fiscal year, when several states were reeling under dry spell, shortage of funds under MGNREGA led to people being denied their entitlements. Further delays in fund transfer affected the work in the states.

As per the affidavit submitted by the centre in the supreme court, the budget cap was removed in 2015-16 as it was the second consecutive year of drought. In 2015-16 (till March 23), the central government spent Rs 49,630 crore on the scheme, the highest in the past five years.

“The present government is not looking at it as a sensitive issue towards the vulnerable, [instead] they are treating these major schemes as the ones started by their political opponent. If the centre delayed fund allocation, states too preferred to remain ignorant,” said Dr Himanshu, associate professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, JNU.

Even delayed wage payments forced downtrodden farmers to migrate towards cities. The national average of wages delayed beyond the statutory limit of 15 days is 62 percent of all wage payments for 2015-16, as revealed in response to an RTI on wages and compensation under MGNREGA.

In 2014-15, a compensation of Rs 506.2 crore was to be paid, of which only Rs 7.5 crore was paid in six states – Jharkhand, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Nagaland and Rajasthan.

In 2015-16, the compensation amount was Rs 216.5 crore, of which only Rs 3.4 crore was paid. The states that paid the compensation were Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Odisha, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Jharkhand, Himachal Pradesh and Bihar. Nearly 90 percent of the compensation payable was rejected by the programme officers on account of insufficient funds available at the time of implementation.

Poor NFSA implementation

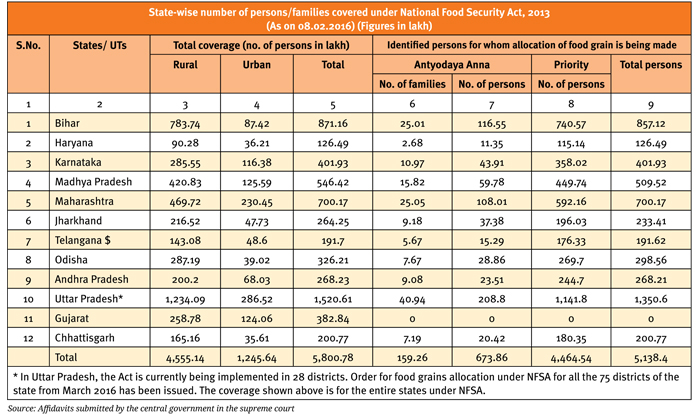

NFSA aims to provide subsidised food grain to the people living below the poverty line. Since its inception in 2013, it has floundered with delayed and flawed identification of households.

During a two-day conference on Right to Food by National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in April, many participants pointed out that villagers are failing to get their entitlements and migrants are failing to avail the benefits in the state they are working in, despite having a ration card of their native village.

Former chief justice HL Dattu said, “There is no dearth of government policies and programmes for ensuring food for all in the country. Questions can be raised only about their effective implementation.”

NFSA ensures monthly entitlement of five kg of food grain per person for eligible households under priority category and 35 kg per family for Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) household at Rs 3 for rice, Rs 2 for wheat and Rs 1 for coarse grain.

Harsh Mander, a human rights activist, said, “MGNREGA and NFSA cannot be looked at separately. Basic focus of the drought relief is the creation of employment. Thereafter, the wage earned can be used to avail benefits under NFSA – buying food grain at a subsidised price. But owing to the government response in the state of crisis, the vulnerable are getting least of the benefits.”

The SC order said that drought-hit areas are to be supplied with heavily subsidised foodgrain under NFSA. It also said that no household in a

drought-affected area shall be denied food grain if it does not possess a ration card, with any proof of residence or identity being sufficient. The ground reality is, however, presenting a contrasting picture.

Drought has led to migration of able-bodied men from villages, leaving behind women, children and the elderly

“People have not heard about the SC judgment. There is no one talking about the entitlements,” said Yogendra Yadav. “In some villages of UP, people are being charged for NFSA slips. We caught hold of a person charging Rs 40 to Rs 60 per slip. The person admitted [to it], saying money has to be given to the computer operator. We spoke to the local inspector and the money was returned.

“As expected, all the powerful [people] in rural areas have managed to get into the priority categories. It is similar to classical cases of classification of beneficiaries in above and below poverty lines. Also, people are not aware of their entitlements and the ration shop owner is the boss, he decides whom to give and how much to give,” Yadav said.

On the other hand, according to the central government figures, the average food grain offtake by eight of the 11 drought-affected states implementing NFSA is much higher than the erstwhile targeted public distribution system (TPDS). Extra food grain was not allocated by the centre in 2014-15.

During the current year, Maharashtra requested for additional food grain, based on which the centre has made allocation of 1.63 lakh tonnes of rice and 2.44 lakh tonnes of wheat.

Overall, the estimated financial implication of implementation of NFSA, at 2014-15 costs is Rs 1,31,086 crore per annum, which is about Rs 27,300 crore more than the TPDS requirement.

Passing the buck

Amid all this, the central and state governments are not ready to take responsibility of dealing with the crisis of drought and its implications. The centre has been sticking to ‘federalism’ saying it could provide financial or any other assistance if it is sought by the state. A declaration of the drought and its management is the concern of states, but many are cannot bear the extra financial burden.

The forecast of above-normal rainfall gives a ray of hope to farmers. But a team of scientists has predicted more frequent and severe droughts in India after 2020 – and that is something that policymakers need to worry about.

[email protected]

(The story appears in the June 16-30, 2016 issue of Governance Now)