The system has failed to value honesty. Also, the judiciary should discern the distinction between administrative mistakes and outright corruption

The recent conviction of former coal secretary Harish Chandra Gupta and other officers by a CBI court in a case relation to allocation of a coal block in West Bengal has raised many questions relating to governance. The case arose from a CBI investigation following the CAG report that government had suffered a loss of Rs 1.86 lakh crore in allocation of coal blocks to the private parties. Later all the allocations were cancelled. The CBI has filed a number of cases in the court. It is interesting to note that these cases under an old law, Prevention of Corruption Act of 1988, continue despite recent major amendments in it. It is doubtful that CBI will find any corrupt action in this case under the new Act.

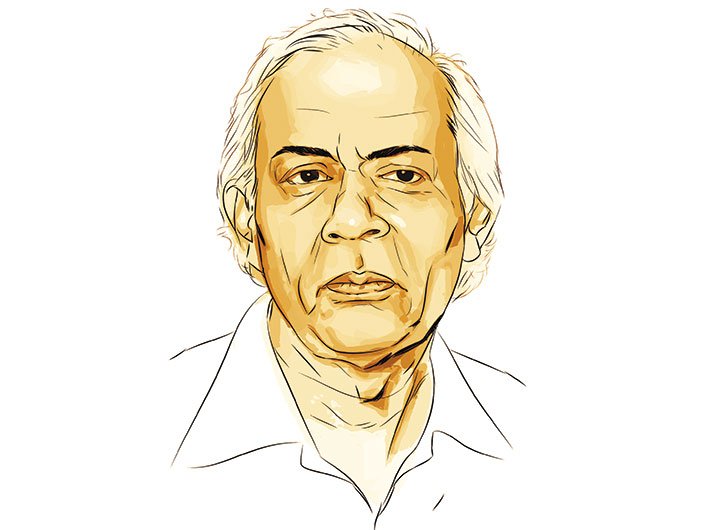

HC Gupta is known for his honesty. Over nearly four decades of his functioning, he is highly respected for his uprightness. I recall how a galaxy of civil servants had emphasised that a civil servant was always respected by the people for honesty. In the National Academy of Administration in Mussoorie I recall how former director, MG Pimputkar, was respected by all for such qualities. I had always maintained that during the long years of service, honesty of civil servants was like a pole star. No harm could come to you if you had this quality. As cabinet secretary I was often invited for lectures. One point I never failed to make was that honest officers would rarely face any problem in the long career. This conviction in the coal case has put a question mark over this view. How can we motivate young officers to be honest if such persons are prosecuted and convicted by the court? Clearly, the system is not valuing honesty.

The decision of the court also raises questions about the method of governance adopted in the country. Most of the decisions in the government and other autonomous bodies are based on discussions in a committee. Decisions about the selection of senior positions in government, like secretaries and additional secretaries, professors of universities, members of the competition commission and by cabinet committees are all discussed across the table. Globally this method is used very widely for decision-taking. In all such meetings all the stakeholders are invited and a decision is arrived at after considering all points of views. Minutes of the committees are generally brief and record the decision of the meeting. A quasi-judicial detailed order is not given for each decision. Even when there are differences in points of views, only a decision of the committee is recorded. For background information on issues involved in the discussion the committees depend upon the stakeholders and field agencies.

It is possible that such decisions may at times go wrong. But one does not send them to jail for this unless there is some malafide or mischievous action which is proved. Such actions have a quid pro quo. There has to be a motive in the form of some benefits to some member for him to take a wrong decision. The court has ignored this approach. It has also failed to realise that there is no way all decisions of any committee can ever be correct but that does not make wrong ones corrupt acts. We must distinguish between wrong administrative decisions and corrupt ones. In the present case, the former coal secretary and other civil servants are being sent to jail despite there being no malafide.

Who is Harish Chandra Gupta?

He is an IAS officer of Uttar Pradesh cadre, 1971 batch. The 70-year old has two postgraduate degrees, in physics and mathematics. He retired as coal secretary in November 2008. He had served as director (coal) in 1987-89.

What is the case against him?

The case in which a CBI court in Delhi found him guilty, is one of the several cases relating to alleged irregularities in coal block allocation in the UPA regime. It pertains to the allocation of Moira and Madhujore (North and South) coal blocks in West Bengal to a company called Vikash Metals and Power Limited (VMPL). Following a CAG report, the CBI had registered an FIR in the case in September 2012. The ‘Patiala House’ court on November 30 convicted Gupta, KS Kropha (former joint secretary in the coal ministry) and KC Samria (the then director, CA-I, in the ministry). It had also convicted the firm. Special judge Bharat Parasar of the ‘Patiala House’ court on November 5 sentenced the three civil servants to three-year imprisonment, though they were also granted bail. The CBI had sought a maximum of seven-year imprisonment.

After the opening up of the Indian economy and abolition of the licence-permit raj, the share of private investments in the economy has gone up. A large number of private players are setting up industries. The share of private power plants has increased rapidly. The telecom sector has seen huge investment. All this has meant a greater number of decisions by the government for award of contracts or issue of licence. When so many decisions are being taken, some will be wrong. I remember a former prime minister, while discussing issues of growth, had mentioned that in the private sector, their managers are happy if 60-70 percent decisions are right. This changed environment in which a modern civil servant works has been completely ignored by the court.

A negative consequence of this decision will be on the approach of other civil servants in taking decisions or undertaking assignments which involve risks in taking decisions. Generally officials are notorious for postponing decision or shuffling files till they are sure that in any future enquiry they will be safe. Government does not punish officials for omission in taking decisions. But it comes down heavily on them, if in retrospect, some decision turns out to be wrong. With the prosecution of such officers like the former coal secretary who worked on resolving the problem of power plants, steel industry and cement plants in a rapidly expanding economy, government is sending a negative signal. Officers will now avoid taking decisions on such crucial economic matters. When they do, it will be fully hedged. We are promoting a culture of ‘no risk taking’ in civil servants. For a growing economy like India, this is very harmful.

The court’s decision also raises a question about the approach of the higher judiciary to the issues of governance. In a democracy and a rapidly growing economy, courts have to take decisions which impinge positively on governance with a very constructive interpretation of our laws. The process of judicial review by the supreme court has led to some major reliefs to the common man. In 1992 justices RM Sahai and Kuldeep Singh interpreted Article 21 of the constitution dealing with the right to life. This they expanded to include the right to education as a fundamental right. The actual constitutional amendment was done in 2002. The scope of the article was further expanded in other landmark judgments to include the right to pollution free water, policies to prevent sexual harassment and rights of tribal women.

The UN Convention against Corruption, to which India is a signatory (2011), has included corruption to necessarily involve some undue benefits flowing to the decision-taker. Recently, government amended the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 and made large changes in section 13 under which the former coal secretary and others have been convicted. The approach now is that corruption must involve mens rea [‘the intention or knowledge of wrongdoing, rather than mere action or conduct of the accused’]. It is now time that the highest court of our country has a fresh look at the old Act and reinterpret its provisions in the light of above facts. It must clarify the distinction between corruption and wrong administrative decisions. That will be consistent with the norm of a civilized society. It will help develop a civil service not shy away from taking tough decisions. That is what the country needs.

(The article appears in December 31, 2018 edition)