Maya Jasanoff’s biography of Conrad revisits his terrifying visions of the tragedy power and capital unleash on hapless indigenous people in pristine forests

When Jozef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski – who became the writer Joseph Conrad – was christened, his father Apollo Korzeniowski wrote him a poem that is in retrospect chillingly poignant.

To my son, born in the 85th year of

Muscovite oppression

Baby son, sleep without fear.

Lullaby, the world is dark,

You have no home, no country...

Baby son, tell yourself,

You are without land, without love,

Without country, without people,

While Poland – your Mother – is in her grave.

The first notes were struck of what would play out as a dark symphony brooding over his life. The sailing ships and steamers he worked on wore foreign flags, and the language he hitched his fictional imagination to was to him equally foreign. As he navigated the world and the contradictions of his life, Conrad was forever striving for an acceptance he felt he deserved but was never accorded. A slow and measured burden of rootlessness floated through his life-song and fiction, making him an acute logger of the global winds and imperial currents of commerce of his time. The map he left traces prescient, ironic courses to a future that is the sombre now of 21st century globalisation.

Likewise, Maya Jasanoff sets off with “the compass of a historian, the chart of a biographer, and the navigational sextant of a fiction reader” through Conrad’s life and four novels in particular – The Secret Agent, Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness, and Nostromo.

Likewise, Maya Jasanoff sets off with “the compass of a historian, the chart of a biographer, and the navigational sextant of a fiction reader” through Conrad’s life and four novels in particular – The Secret Agent, Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness, and Nostromo.

She throws grapnel lines, or in the language of the internet, creates hyperlinks as it were, to the personal and historical events of the landscapes, seascapes and inscapes of Conrad’s life and his fiction. From their joining up in the reader’s mind, Conrad emerges as a grim silhouette on the ratlines, keeping an endless dawn watch on a human horizon that never glows with morning light.

Jasanoff points up many coincidences. Berdychiv, the town Conrad was born in, was synonymous in Polish adage with ‘nowhere’: in effect, he was born nowhere, its penumbra cast from a distance in time over his lifelong outsider status. In 1857, the year of his birth, the world was already witnessing telling effects of the colonial ‘globalisation’ of that time: Chinese settlers rebelled in Borneo, in a Malay state ruled by a white rajah; a bank failure in Ohio bankrupted businesses in Hamburg; a mutiny of Indian troops swelled into rebellion against the British. By the time Conrad was 57, and visiting his native land with his English wife and children for the first time since he left it to be a sailor, the assassination of an archduke of the Austro-Hungarian throne by a Serbian nationalist was enough to march half the world into the muddy trenches of the Great War of 1914-18. The Conrads had arrived in Krakow, now under the Austro-Hungarian empire, on the very day it declared war on Serbia and spent all of that looked-forward-to trip working a passage back to England.

Without sentiment, she uncovers life facts that Conrad either did not dwell on or rationalised or romanticised away. His shooting himself in the chest at age 20 was almost certainly a parasuicide, driven by the need to get his uncle and guardian Tadeusz Bobrowski to release the money that would clear his debts. Conrad was a middling mariner, passing the exam for his master’s certificate only in the second attempt. In the nearly 20 years since going to be a sailor to deciding to quit seafaring, he had spent only eight years at sea, the rest a wait for assignments, often below his rank. And for all his railing against the steamship and his worship of the sailing ship and the craft that brought sailors into subtle communion with the wind and tide and current, Conrad did take assignments on steamers. Indeed his trip on the Congo, that became Heart of Darkness, was on a steamboat.

The core of the book addresses itself to locating the events Conrad witnessed or heard about, the people he knew or heard seamen talk about, making an appearance in his works either as direct transplants or transmuted by his fictional imagination.

Tippu Tib, a Swahili-Zanzibari slave trader, and others like him who supplied the Belgians with ivory, turn into the composite figure of ‘Mistah Kurtz’ of Heart of Darkness. The abandonment of the S.S. Jeddah by its crew reappears as the albatross around the neck of Lord Jim. The Secret Agent, ironically subtitled ‘A Simple Tale’, builds a chilling family drama of amorality around a failed attempt to blow up the Greenwich observatory in 1894.

The story was paramount to Conrad, not the themes that arise like vapours around it. And yet, by working on the story and its telling alone, he allowed universal themes to emerge, all in the grimmest twilight tones: man’s, and hence civilisation’s, insatiable capacity for depravity; the mindlessness that drives anarchist and terrorist groups; the relentless march of power and material interests through jungle villages of innocence.

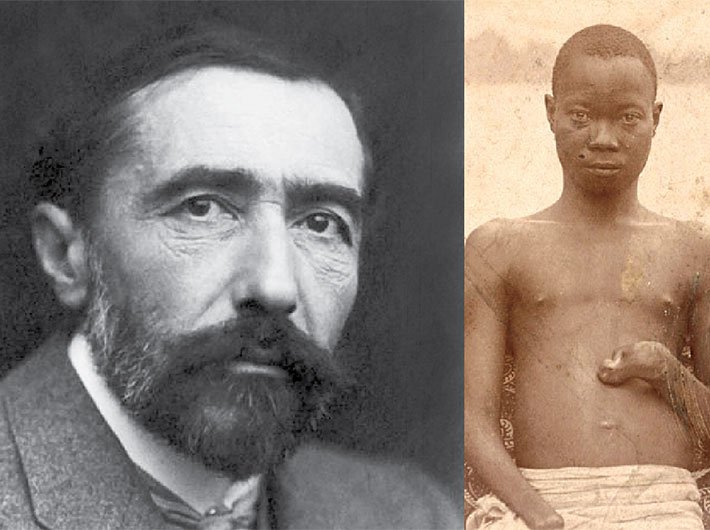

Conrad’s indifference to politics may have stemmed from viewing his father’s patriotism as ineffective. In the Congo, he had made friends with Roger Casement, whose report on the atrocities perpetrated by the African International Association (the enterprise King Leopold II of Belgium created to take over the Congo) in its quest for ivory and rubber shocked the world as much as Heart of Darkness did. Like the missionaries, he had documented the cutting off of the hands of tribespeople: native soldiers of the Force Publique, serving under Belgian officers, were told to account for the bullets they used, so they would just get hold of natives and cut off their hands. Later, when Casement was sentenced to death for his activities as an Irish nationalist, his friends petitioned for reprieve. Conrad was among those who did not put his signature to the appeal.

Jasanoff mentions this without much comment, as she does Chinua Achebe’s indictment of Conrad as a racist who only used Africa as a setting for a white man’s degeneration, as “the antithesis of Europe and therefore of civilisation, a place where man’s vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality”. It is as if she absolves Conrad of those allegations for the strength of his storytelling, his evocation of human themes larger than and beyond the particularities of race or culture.

The portentous lines Conrad drew thread their way into a 21st century in which the internet has taken the place of the transoceanic telegraph cables of his time; online chatrooms buzz with anarchy and religious terror like the dingy rooms in which his comically dangerous idealisers of the bomb-concealed-within-the-overcoat conferred; and, like in Nostromo, superpowers and governments in symbiotic bondage with corporate interests rampage through hapless nations and peoples.

The immediacy of that was brought home to India when the supreme court, in a judgment of 2011, compared Chhattisgarh’s police and militia actions against tribespeople to what happened in the Congo of Heart of Darkness: a “warped world-view that parades itself as pragmatic and inevitable” trampling people as it scours the earth in an “unquenchable thirst for natural resources”. All around us, we see those forces unleashed.

The epigraph to Jasanoff’s book is a chilling line from Victory, in which the mercenary Jones, on visiting Axel Heyst, says, “I am the world itself, come to pay you a visit.” It was, for Heyst, a visit with tragic consequences. Conrad wrote that his artistic aim was “by the power of the written word to make you hear, to make you feel – it is, before all, to make you see”. The Dawn Watch makes us see again, through the grey fog of our complacence, the tragedy set into motion when a world riding on commerce visits indigenous communities anywhere.

For Conrad fans like this reviewer, the work is more than literary biography, more than research, more than a good read. Like Conrad’s archetypal storyteller Marlow, who appears in Chance, Youth, Lord Jim, and of course Heart of Darkness, it builds meaning as the haze of a glow around Conrad’s works and his life rather than offering it as a shelled kernel.

(The book review appears in the April 15, 2018 issue)