An excerpt from a new work that studies the institution of the President of India

The Indian President: An Insider’s Account of the Zail Singh Years

By K.C. Singh

HarperCollins, 312 pages, Rs.699

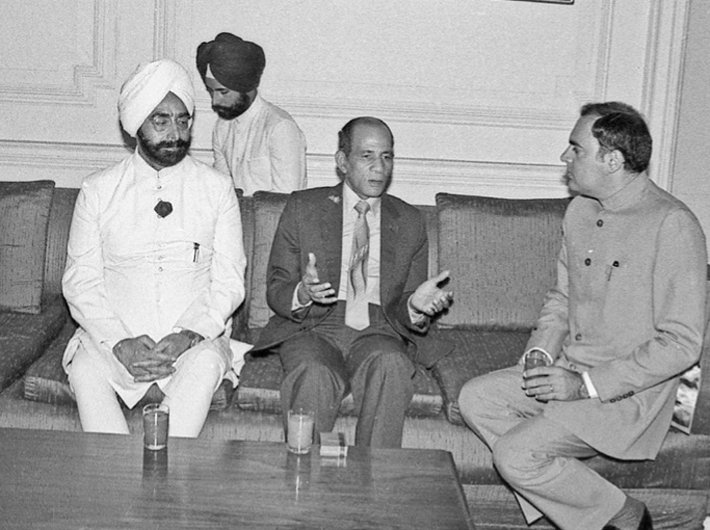

A study of the institution of the top constitutional office of the republic, this book is based on Ambassador K.C. Singh’s term as deputy secretary to the seventh president, Giani Zail Singh. In particular, it examines the president’s role when authoritarian governments are voted in power. Things are all the more challenging for a president with a popular prime minister who has an overwhelming majority, as happened in the case of Zail Singh and Rajiv Gandhi.

A study of the institution of the top constitutional office of the republic, this book is based on Ambassador K.C. Singh’s term as deputy secretary to the seventh president, Giani Zail Singh. In particular, it examines the president’s role when authoritarian governments are voted in power. Things are all the more challenging for a president with a popular prime minister who has an overwhelming majority, as happened in the case of Zail Singh and Rajiv Gandhi.

The book recounts how the guardrails painstakingly created by the first two presidents – Rajendra Prasad and S. Radhakrishnan – were partly resurrected by Zail Singh. Richly anecdotal and incisively observed, ‘The Indian President’ makes a compelling case for why the Zail Singh years are crucial to understanding both the limits and the possibilities of the country’s highest office.

According to the author, “The President of India is constitutionally mandated to play a stabilising role in a maturing democracy with myriad conflicts of interest and views. Office holders swear to protect and defend the constitution. That oath has been historically inconsistently observed. The book deciphers the past to ensure, as the saying goes, that India is not condemned to repeat it.”

Singh joined the Indian diplomatic service in 1974 and retired in May 2008 as secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs. Besides serving in Cairo, New York and Ankara, he was deputy secretary to the president of India (1983–87), and JS(XP) and spokesman for the Ministry of External Affairs (1998–99). He was ambassador to the United Arab Emirates (1999–2003) and to Iran (2003–05). He is now a columnist and strategic analyst for national and international affairs.

Here is an excerpt from the book:

The Endgame (1987)

THE government had passed the Post Office Amendment Bill in 1986. In early 1987, there was already debate on the possibility of the president withholding his assent to the bill. The controversy surrounding it continued to brew in the print media. Realizing that public opinion was turning against the government’s attempt to acquire broad powers to snoop on their mail, the president decided to sit on the bill. Meanwhile, he continued to discuss his constitutional options with select legal experts.

Giani ji realized that if he returned the Postal Bill, the government, with its brute majority, would quickly resubmit it for presidential approval. In that case, it would be mandatory for him to give assent, as per the forty-fourth amendment to the Constitution in 1977. He could seek the views of the Supreme Court, but Justice R.S. Pathak, the new Chief Justice, had just been sworn in on 21 December 1986 and was in the flush of government benediction. He was also the son of a Congress loyalist who had been elevated to vice president. In any case, the president was cynical in his assessment of the holders of constitutional posts, convinced they may buckle under pressure or, worse, cut a deal with the government.

He decided to adopt a common-sensical approach to the subject. He asked his legal interlocutors if the Constitution provided any timeframe within which the president was

required to apply his mind. A strict interpretation would be that the application of mind could not be an open-ended process. But these were exceptional times. A young prime minister with an overwhelming majority, rendered captive by the anti-defection law, was steamrolling an anti-people measure through. The president was always insistent that his oath, unlike that of other holders of constitutional positions, was to uphold and defend the Constitution. Therefore, the ends justified the means, if they were not contrary to the letter of the law.

As someone who had read law, I always found it interesting to debate constitutional provisions with Giani ji. He was not a law graduate, but his training had been in the court of the people, and he used common sense to debate and parry. He could discuss it with equal aplomb with constitutional experts, who were often tripped by his logic. He therefore decided to just sit on the Postal Bill. He had public opinion on his side. The only recourses Rajiv Gandhi had was to keep squirming while the issue remained alive or back down and withdraw the bill. Alternatively, he could attempt to impeach the president, for which he did not have the numbers in Rajya Sabha. The president exercised what some have described as a ‘pocket veto’.

The prime minister decided on a strategy of attacking the president. Friendly journalists were shown classified Ministry of Home Affairs files that the president as home minister had supported a similar bill. But times had changed. The press did not take the bait. The president was acting in an entirely different capacity. He was now the custodian of public good, and not a partisan minister.

There was an earlier precedent set by President Prasad, who had aired his objections to the Hindu Code Bill, causing Prime Minister Nehru to eventually back down. President Prasad had

used the argument that a Constituent Assembly, elected to draft the Constitution, cannot legislate on an issue that had not been taken to the people. It is an argument that can be applied to most governments, often enlarging their agenda after winning a mandate. Nehru had two handicaps that Rajiv Gandhi did not. One, he did not have the anti-defection law and thus lacked a legal stranglehold over his party. Also, the Congress then had stalwarts who had been Nehru’s colleagues in the freedom struggle. Rajiv Gandhi had no such constraints or relationships, as his mother had over time reduced the Congress largely to timeservers and sycophants.

Unmindful of the fact that he already had adverse public opinion building up over the Postal Bill, Rajiv Gandhi in a 19 January press conference, where Foreign Secretary Venkateswaran was present, informed the media that they would be getting a new foreign secretary soon. The unprecedented public sacking of any senior civil servant, but certainly one of Venkateswaran’s public standing, was bound to stir a storm. Pandemonium ensued as Venkateswaran promptly put in his papers. Pressure and cajolement were employed to find a face-saver for the prime minister and an honourable exit for the foreign secretary. The IFS Association rose to the occasion. Despite pressure from senior levels, it passed a resolution affirming support to their unfairly targeted boss, emphasizing that it ‘undermined the morale of the service’.

The president sent me to Venkateswaran’s residence in the evening, which is now the designated house for foreign secretaries on Circular Road in Chanakyapuri. Giani ji was keen to see if there might be a compromise in the works. There were just me and the joint secretary (personnel), Ministry of External Affairs, at his residence. Venkateswaran had absorbed the punch and had no desire to withdraw his resignation. He quickly moved out of the official residence. I thought he had positioned himself perfectly for a stint in politics or at least in public life. Some months later, he took up a job with a Hinduja trust.

The Hinduja family is a renowned expatriate group operating out of London, Geneva and India. Their business past is traceable to Iran, where I was to bump into them some three decades later as ambassador to the country. But in 1987, the shadow of a past misunderstanding with the Gandhi family lingered over earlier defence deals. It was also not foreseeable then that the Hindujas themselves would soon be back in another arms-related controversy. At a subsequent meeting, at Venkateswaran’s rented house in Shantiniketan, he conceded that he was compelled by financial insecurity to opt for a corporate sinecure over politics.

[Excerpt reproduced with the permission of the publishers.]