Thousands of kilometres away, in Kyoto, nothing is like Kashi. Back in Kashi, nothing is like Kyoto

Ganga ke jal mein apni ek taang par khada hai yeh shehar

apni duusri taang se bilkul bekhabar

– Hindi critic and essayist Kedarnath Singh in one of his poems

Posted in Varanasi as an assayist at the mint, James Prinsep, the self-taught polymath famed for deciphering the Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts, mapped the ancient holy city and concluded its first census in 1822. He decided that Varanasi, then home to about 1.5 lakh people, needed a sewage system. Over the next two years, the young engineer built an intricate network of drains and underground conduits that are even today praised as a marvel.

The businessmen and priests of Varanasi, settled there from various parts of India (for even then it was a cosmopolitan city) wanted to make a gift to their Banarasi angrez, as they called Prinsep. As a token of affection, they gave him a plot of land. Prinsep, who was in love with the city and made several lithographs of scenes of Banarasi life in those times, designed and built a mandi on the plot and gave it back to the people. Named Visheshwarganj, the marketplace had embankments with a number of porticos lined with shops. Vendors could also set up their wares, and accountants could carry on their trade. The wide road on either side of which the marketplace came up led towards the Machhodari area and also connected the market with the Ganga, on which boats would ferry cargo to nearby cities and towns.

Like his network of sewers, Prinsep’s market is still functional and caters to wholesalers in grain and grocery, spices and textiles from all of eastern Uttar Pradesh and western Bihar. But the city has failed his brilliant planning by not scaling up as it grew in population and square kilometres.

Back in 21st century

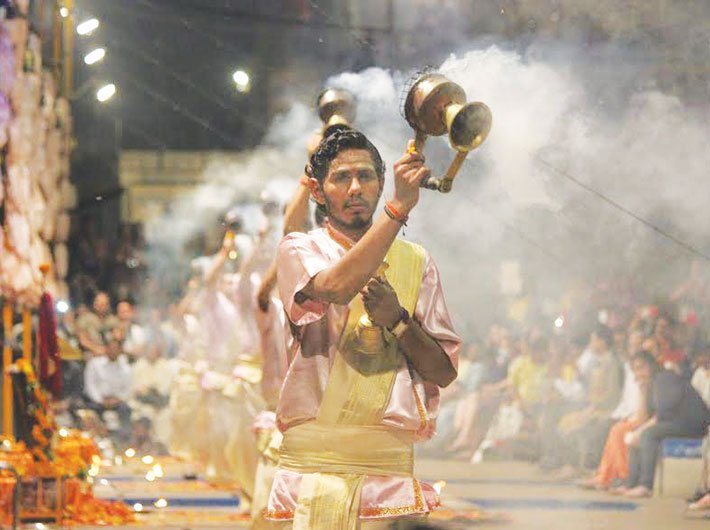

As dawn breaks over the Ganga in Varanasi, sounds of temple bells and the morning azaan spread through the congested lanes. Golden light streaks the river, from the green fields on the eastern banks to the ghats suffused in a gentle warmth on the western bank. Devotees start taking holy dips, priests perform rituals under the bamboo parasols, tea-vendors briskly go from one ghat to the other, offering chai in kulhads (earthenware cups). Everything seems serene. Meanwhile, Visheshwarganj market comes into its own. Shops begin to open. The municipal workers have swept the claustrophobic lanes leading to the northern end of the Ganga, so they look relatively clean. People are seen reading newspapers in groups and bartering political gossip. The early morning delicacy of jalebi and kachauri-sabzi is ready to serve, and the streets are already being littered with donas and pattals (plates and bowls made out of dried leaves). A man in his 40s throws his plates by the wayside, grins as he talks to a shopkeeper, kickstarts his Bullet bike and thunders away. Temple waste, mainly votive offerings of flowers and leaves, lies piled in the street corners. “Municipal workers will take it away and dump on other side of Ganga,” says a man swirling jalebis in a giant kadhai full of oil.

In no time, the market becomes crowded, the traffic flow increases. In the narrow lanes, bicycles, motorcycles and scooters manoeuvre past cars and black-and-yellow autorickshaws, school buses and garbage collection vehicles. Foul emissions burden the air. Resting on medians, bulls, cows and stray dogs contemplate this urban madness, as now and then, followed by mourners, pall-bearers carry the dead on bamboo biers towards Manikarnika ghat for cremation. Even the dead have to clear this chaotic hurdle.

At the Maidagin crossroad from where you enter the market, it seems everyone wants to go everywhere. Flags, flex boards and bills advertising pickles, paints, farm produce, spice mixtures cover up the shop fronts. On one side of this road is an area where vehicles bringing the dead for cremation are parked. There are frequent jams that, if you are lucky, clear in 10-15 minutes, but most often take up to an hour. Men from the shops nearby step in as traffic managers to keep the vehicles moving. All the same, the honking is continuous – enough to make you wish you could go away somewhere, perhaps to a ghat as placid as Prinsep pictured it in his lithographs, to the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) campus, or to the Sarnath stupa, across the river. Long time residents who have read Diana L Eck’s book City of Light wonder what made her call Varanasi the “city of good life”.

This is how Visheshwarganj market, designed by James Prinsep in the 19th century, looks today

During the monsoon, many parts of the city are nothing short of an unholy mess. Unlike the Banarasis of the 19th century, residents have to wade through knee-deep water in the old city areas whenever it rains. The centre and the state government have sponsored many projects to control water-logging and sewage backflow, but the results are yet to be seen. The structures that Prinsep designed are all crumbling – and it’s happening in a constituency represented by prime minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party, who chose to contest from here because of its symbolic significance.

Says OP Kejariwal, a former bureaucrat, historian and author of Benaras Illustrated, based on Prinsep’s illustrations of the town, “There was no modern or planned development before Prinsep’s 10 years’ work in the city. And we can say the city has been left to deteriorate ever since he left. The population has grown from 1.5 lakh in 1824 to 36 lakh in 2017. The maximum deterioration has taken place in the last 60 years. The architecture, urban design, town planning, sewage and garbage management, every aspect of urban development has moved out of gear. With its bad civic sense and lack of any town planning, the city is slowly committing suicide every day.”

Behind the Banarasi masti (joie de vivre) and phakkarpan (nonchalance), runs a Ganga of urban despair.

The JnNURM game

In early May, the Swachh Survekshan survey rankings were announced by the urban development ministry: to the surprise of many, Varanasi was ranked 32nd. In fact, the ranking had leap-frogged ahead from 418th in 2015. Locals sensed a foul smell in the assessment, for garbage remains piled for days, sewages overflow or get blocked, filthy water gathers in many places. The municipal corporation estimates that the city generated some 650 million litres of sewage daily. The treatment plants just can’t handle it, and a large quantity of it flows into the Ganga untreated via open nullahs.

In 2006, the UPA government commissioned several projects under Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM) to deal with many urban problems: sewage management, Ganga pollution, drinking water shortage. Sewage disposal was revamped, and much of the city was dug up for laying new sewers. From 2007 on, roads have been dug up one after another. Many a time a road has been dug up more than once in a span of just a couple of months. Says Reeta Singh, a retired schoolteacher, “We have become used to this. If they dig up a road, they don’t repair it. If one sewer is laid, they dig the road again later to replace it.” This continued for about four years, but the local administrators could not decide where to build the sewage treatment plant. Things just stand there. Several tanks for storing and distributing water have also been built under JnNURM, but they just stand useless: there are apparently technical issues about handing them over to the state government for water supply.

Another JnNURM project was the solid waste management plant on the city outskirts, which ate up Rs 48.67 crore. Varanasi generates 600 tonnes of solid waste daily. In 2009, a Gurgaon-based company, A2Z, was designated to collect garbage door-to-door, segregate and convert organic waste into compost and use the remaining for landfill. While A2Z started collection garbage, the plant was still under construction. Thus, garbage was dumped in nearby villages and the Varuna riverbed. Unhappy with their work, Azam Khan, the then state urban development minister, scrapped the deal with the private company. This increased the pressure on the municipal corporation, which was already inefficient in cleaning the city. From 2014 onwards, two other private agencies have been engaged in garbage collection in the city. The solid waste plant still is not fully functional and the garbage is treated only enough to be used for landfill.

Even as none of the work was undertaken, the Modi government took over and renamed JnNURM as Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT). But the logjam continues.

Transport travails

If you are relying on public transport in Varanasi, you might keep waiting for hours before you reach your destination. The buses purchased under the JnNURM are few, and they connect only some parts of the city. Plus, not many people use them because the buses frequently get stuck in traffic, leading to long delays. So pedal-rickshaws and autorickshaws are the only reliably modes of transport – else you have to use your own vehicles. The centre cleared a Varanasi metro project earlier this year but people are sceptical, given the pace at which JnNURM projects have proceeded.

City for all

Although Varanasi is considered one of the most important Hindu pilgrimage centres, it is equally important to Buddhists and Jains. The Buddha is believed to have given his first sermon in Sarnath, and Parshvanatha (the 23rd thirthankar of Jainism) is believed to have been born in Banaras. Adding to Varanasi’s syncretic charm are Muslims, who constitute 30 percent of the population. Many of the weavers of the famous Banarasi saris, which generally have Mughal motifs in repeating patterns, are Muslims, as are many exponents of Hindustani classical music. The city has Bengali, Gujarati, Marathi, Kannada, Tamilian and Telugu quarters, where people from these parts of India have been living for ages. Of course, it all began with people coming here on pilgrimage from across India over the centuries. There is one locality, near Manikarnika ghat, which has been home to Jews since the 19th century. The ghats themselves have a story to tell: they were built by kings from various parts of India from the 14th to the 19th century, because people from those places would visit Varanasi for pilgrimage or education. “It’s not wrong to say that Varanasi is the oldest cosmopolitan of the world,” says Rajesh Gupta, who runs a 40-year-old shop in the famous Vishwanath gali. Even today, the guesthouses and motels in the serpentine lanes, brimming with backpackers, and offering everything from yoga and music lessons to WiFi connectivity, mark out Varanasi’s cosmopolitan character. The boards advertising them come in Japanese, Chinese, Russian, and even Hebrew.

Despite its many problems, Varanasi attracts tourists from across the globe. After Agra and Jaipur, it is the city most tourists like to visit. Backpackers and spirituality hunters of a certain outlook seem to find serenity in chaos, peace in the cacophony and madness. Many of them come here once and then return again and again, for the study of yoga, music, ancient languages like Sanskrit and Pali, for the peaceable lull of bhang and ganja. Not for nothing is the city listed among the 47 on UNESCO’s creative cities network.

The city is still celebrating its status of one of the oldest cities, its great history and political and religious significance. But it is yet to see achhe din. Thousands of kilometres away, in Kyoto, nothing is like Kashi. Back in Kashi, nothing is like Kyoto. The Kyoto-Kashi pact has been reduced to a sarcastic idiom for use by locals. Even so, this ancient city has the potential to become a good, livable city – without diluting its identity and without being compared to Kyoto.

(The story appears in the June 1-15, 2017 issue of Governance Now)