Interview with Roland Adjovi Setondji, vice chair of the UN's Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) that ruled in Julian Assange's favour last week

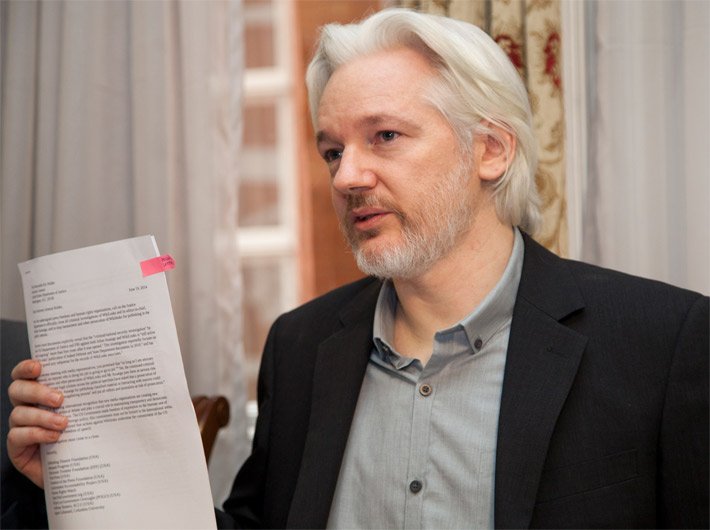

The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD), a United Nations body of independent human rights experts, has adopted its ruling on Julian Assange, founder of WikiLeaks, announcing his deprivation of liberty as arbitrary and asking the governments of Sweden and the UK to ensure his freedom of movement. The WGAD, established in 1991 to investigate and adjudicate whether states are in compliance with their international human rights obligations, had five panelists on the Assange case. Out of them, Vladimir Tochilovsky, a Ukrainian expert, dissented with the majority view and another Australian expert Leigh Toomey recused herself. The rest of the panel comprising Seong-Phil Hong from Korea (Chairman-Rapporteur of the WG), Jose Antonio Guevara Bermudez from Mexico and Roland Adjovi Setondji (Vice-Chair of the WG) from Benin delivered a favourable opinion on Assange’s complaint of arbitrary detention against the UK and Sweden. Roland Adjovi, who is also an assistant professor of historical and political studies at Arcadia University, US, spoke to Shreerupa Mitra-Jha on the panel’s decision:

Why did the WGAD panel rule that Assange is under arbitrary detention?

You have different forms of detention and they are not all physical detention. For instance, a house arrest is still detention for the Working Group. In fact, the concept which better reflects our mandate is deprivation of liberty which includes any situation of restrictions on liberties. In our view, the situation he was in – in prison, house arrest or bail situation before running into the embassy, are all a situation of deprivation of liberty. And it’s a continuity.

You have different forms of detention and they are not all physical detention. For instance, a house arrest is still detention for the Working Group. In fact, the concept which better reflects our mandate is deprivation of liberty which includes any situation of restrictions on liberties. In our view, the situation he was in – in prison, house arrest or bail situation before running into the embassy, are all a situation of deprivation of liberty. And it’s a continuity.

The arbitrariness of that detention comes from two elements: first, the ten days he was in prison in London was in isolation. And there was no ground for that isolation condition. So that is already a violation of his right. We ask ourselves why he has been deprived of liberty over the last five-six years. It has only been on an allegation being investigated. Why over six years they could not conclude on the investigation and go on trial? That length of time is too much, in our view, and violates his right to a fair trial.

Now this outcome has nothing to do with the criminal case he has in Sweden contrary to what the British media are saying and how so many journalists are analysing the opinion. [It] has nothing to do with the seriousness of the crime alleged in Sweden. If they are so serious for the Swedish prosecutor herself, why can’t she make up her mind as to whether to indict Mr Assange or not? We cannot afford a criminal justice which allows or tolerates violation of the rights of the suspect or the accused. It is not the type of system we want to live in for any society to abuse the suspect or accused in the course of doing justice to the victim. The quality of justice delivered for the victim is based on how much you respect the suspect and the accused.

According to the 1951 Refugee Convention, if you are seeking asylum on the basis of non-political crimes then your application may not be respected by the State. What were the deliberations within the panel on that?

In our view, we didn’t have to look into the asylum/refugee law situation. The facts before us were sufficient for us to decide on the key question without getting into that dimension of the case. So I can’t make any comments on this.

To be clear, Sweden has not filed charges against Assange and the US has not asked for extradition…

Right now, Sweden has not indicted him formally. [Regarding] the US we have no idea. All kinds of “rumours” or hearsay we are hearing have no relevance in our case as decided.

The Ukrainian expert who has dissented from the panel’s opinion has said that it is not a deprivation of liberty but rather a restriction of Assange’s liberty…

That was his view. I can’t comment on his view. He has a right to hold a view that we are not in agreement. That’s how we arrived at a majority decision.

As an international law expert, what happens when a country dismisses a UN panel ruling, like the UK has done? Is there any enforceability mechanism?

The WG has no power to enforce its own opinions, like most if not all international judicial or quasi-judicial bodies. We will certainly report to the HRC (human rights council) whether the two States have complied or not. That is the extent of the power granted to us by the States through the HRC. It is then for the HRC and all States interested to take the political measures that they deem necessary. For instance, in some instances, the conditionality of aid given to countries around the world could find its origins in these sort of opinions which demonstrate a violation of human rights. Through the Universal Periodic Review, you can see how States are using these types of decision against each other in their examination. In short, the risk is essentially political.

But there is another dimension: if Sweden and the UK are not complying with that outcome, what would be their credibility in calling on other States to comply with human rights? Especially when while doing so, some of their officials use disparaging language against the WG. All these call in question the stand of States on the right side, on the side of protection of human rights wherever they are violated.