Consistency is often seen as banal and non-intellectual ever since Karl Marx coined the phrase, “History repeats itself; first as tragedy and then as farce”. Consistency, the cliché goes, is hobgoblin of little minds. But Ralph Waldo Emerson was actually talking about foolish consistency. The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) has not made a fetish of foolish consistency, and it has indeed changed with changing times – but with a consistency of objective, of its broader discourse.

Still, critics fail to notice this consistency, as it has happened again after the RSS organised a three-day conference in mid-September to reach out to critics and non-conformists of Delhi’s elites.

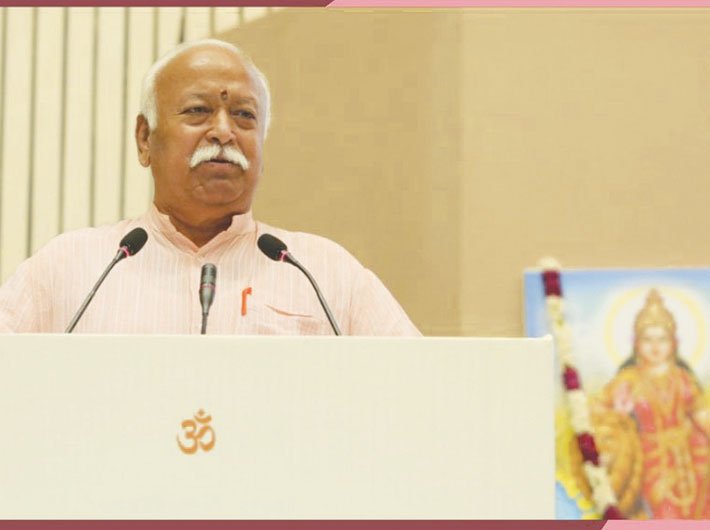

When RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat, in his September 19 address on ‘Bharat of Future: An RSS Perspective’, insisted on his organisation’s inclusive (yukt) approach to society, some have analysed it as a rap on the knuckle of the BJP’ political leadership which is bent upon making India free of the Congress (Congress-mukt Bharat). His praise for the older generation of the Congress leadership is seen as a well-deserved rebuke to an “upstart” BJP leadership that is apparently drunk on the arrogance of power. Some have drawn vicarious pleasure from what they perceive as the emerging dissonance between Bhagwat and the BJP leadership on national issues as they find the opposition led by Rahul Gandhi quite inadequate to weave an effective counter-narrative.

But a glance at the RSS history would be indicative of a canny consistency with which it has been approaching the national issues and changing its views with the changing times. Over the decades, the RSS has adapted itself to the transformations in Indian society and polity, and recalibrated its approach on various issues. The conference at Vigyan Bhavan in Delhi was an important sequel to that change.

Right since the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, the RSS has faced many trials and public scrutiny to establish its credentials as a genuine “socio-cultural organisation” committed to the consolidation of the Hindus. It was proscribed by Jawaharlal Nehru in 1948 after Gandhi’s murder and again by his daughter Indira Gandhi in 1975 after the imposition of the Emergency. On both occasions, the RSS was blamed for carrying out a “secretive and subversive mission” that promoted violence and disaffection in society, a charge that has been levelled quite frequently and liberally but never proven legally. And this formed the basis of a perception about the RSS which continued to be understood from a particular prism.

But the remarkable flexibility that the RSS leadership had often shown to adapt to the times is often ignored to perpetuate a particular narrative that stereotyped the RSS and its constituents. Now let us recall the manner in which the RSS, under Balasahab Deoras (the third Sarsanghachalak during the eventful period between 1973 and 1994), had thrown itself open for Muslims in the post-Emergency phase. This was a transformative event for an organisation committed to the cause of the Hindus.

There is no doubt that Deoras’s move was audacious even as it evoked criticism from within the fold. In an authentic account of that period, Lost Years of the RSS (2011), Sanjeev Kelkar refers to the criticism faced by Deoras and points out that Maharashtra RSS chief KB Limaye wrote a letter expressing his anguish. His letter reads, “You have been given the position of the chief of the RSS of Dr Hedgewar. Kindly run that Sangh and try to foster its growth. Do not try to change it. If you think a change is necessary, start a new RSS. Leave the RSS of Doctorji for Hindu consolidation to us. If you change this RSS, I will not be able to have any relationship with that Sangh.” Of course, Deoras remained unfazed and continued with his experiment.

It will be quite instructive to know how this new experiment came about. When Indira Gandhi had put Deoras and many other RSS functionaries in jail during the Emergency, they found themselves in company with leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami. Both took the opportunity to interact with each other and got to know each other better while the tyranny of the Emergency was at its peak. In the post-Emergency phase, Deoras displayed an enormous sagacity not only to let its political affiliate, Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS), merge its identity with the Janata Party but also promised to undertake initiatives to dispel misconceptions about the RSS. He allowed Muslims to examine the RSS from close quarters.

Those who are surprised at Bhagwat’s assertion that Hindutva would be incomplete without Muslims are oblivious of yet another instance which was quite radical in its approach. After the Emergency, a group of Muslim clergy went to meet RSS leaders at its Nagpur headquarters. As the discussion was prolonged, they became anxious as it was time for their namaz. The hosts asked them if they could offer prayers there itself – within the RSS headquarters – and they said, yes. Indeed, that day the group of Muslim clergy said their prayers in the RSS headquarters. Perhaps, against the backdrop of the Emergency, the bonhomie between the RSS and the Muslims was at its peak. If you have any doubt then look at the utterances of Mohamed Ali Currim Chagla, a noted jurist and former union minister, who praised the RSS and described himself as “Muslim by religion and Hindu by race” much to the annoyance of orthodox Muslims and liberal Muslims alike.

The end of the Emergency did not mean an end of the RSS’s travails. The BJS members who were now part of the Janata Party were targeted over the ‘dual membership’ as socialists questioned their allegiance to both the party and the RSS. However, much before the issue of the dual membership was raised as a pretext to break the Janata Party and bring down the anti-Congress coalition, there were several instances when the tallest leaders from the socialist block, like Madhu Limaye and Madhu Dandvate, sang paeans for the RSS and its contribution to nation building. When the wrangling began in the Janata Parivar over the RSS, Deoras promptly issued a letter that freed its workers to follow their discretion in choosing a political course. The implicit message was that the RSS would not influence its volunteers’ political preferences. Once again, Deoras faced sever criticism within the saffron fold for his move.

Now read Bhagwat’s statement on Muslims with the post-Emergency changes brought about in the RSS by his predecessor, you will find a consistency. This clearly flies in the face of argument advanced by intellectual patricians (ironically drawn mainly from the Marxist stream) that the RSS is driven by a pernicious ideology that promotes orthodoxy, dogma and intolerance. Perhaps the RSS leadership has faced more criticism from within for pursuing a course of reform that runs contrary to traditionalists beholden to dogmas. Bhagwat’s exposition in Delhi is perfectly in sync with the organisation’s unique flexibility to adapt to change.

A long history of transformations

In the post-Emergency phase, the RSS was accused of being run by largely Brahmins and other upper castes significantly biased against backward and scheduled castes. This allegation was liberally levelled majorly by socialists who found the Sangh steadfastly refusing to play second fiddle to their politics.

Though the issue of dual membership substantially emanated from a group of socialist leaders’ inability to make the Sangh amenable to their designs, Deoras hit back. He released a list of RSS senior leaders who belonged to various caste groups across the country while pointing out that socialist formations were led largely by Brahmin leaders. In the seventies, the RSS had drafted a large section of socially and economically marginalised sections within its fold.

The emergence of many OBC leaders as icons of Hindutva was not an overnight development. Prime minister Narendra Modi’s emergence as the tallest Hindutva leader belonging to a backward class is consistency of the history of the RSS and not a freak accident. And it will be naïve to drive a caste wedge within the Sangh Parivar on the basis of dalit versus upper caste or OBCs. Far from creating a division, the Sangh Parivar would emerge much stronger should there be a dalit Hindutva icon like Modi. Given the radical transformation of the Sangh Parivar’s cadre base, such a probability is not far-fetched.

Perhaps the understanding about the RSS and its various constituents is marked by a serious intellectual deficit. The saffron family is seen in a typical binary which either valorises or vilifies it. It is not that there were no serious studies on the RSS and its constituents. In a brilliant study of the RSS in 1951, JA Curran Jr., an American scholar, presciently observed, “It is popularly believed that the Sangh will, in the event of gaining power, automatically support vested interests – capitalist, landlords and others. The author considers that, while a number of RSS sympathisers and supporters, particularly those in the group just described, look to the Sangh as potential guardian of their specific interests, there is no pronounced enthusiasm among most swayamsevak[s] for any such role. Despite the lack of formal economic program, there is a strong vein in the Sangh ranks of what might be called Hindu socialism.” This study had been carried out before the RSS’s political arm, BJS, was born.

The subsequent events proved Curran’s prognosis about the Sangh Parivar’s politics right. For instance, the BJS pitched not only for abolition of zamindari and privy purse much against the general impression that the party would side with the liberal and open economy. It suffered electoral setbacks for this stance. In terms of economic agenda, the Swatantra Party offered more cogent response to the Congress than the RSS-BJS combine. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s “integral humanism” was considered to be a muddled-up response to the Congress’ gradual drift towards socialism.

Till 1967 when the BJS forged an alliance with the socialists, Swatantra Party and hardliners like Hindu Mahasabha and Ram Rajya Parishad, it kept on changing its goalposts and adapted itself to changing circumstances. Yet the underlying theme of all these efforts was a larger cause of consolidation of the Hindu society which apparently ran contrary to the dominant Nehruvian political narrative of those times. That was the precise reason why the RSS-BJS earned the tag of being communal. But what is significant is the refusal of the Sangh Parivar to be guided by a doctrinaire approach to Hindutva which was akin to adhering to Brahminism. This flexibility was retained only to accommodate various social groups within the Hindus that follow rituals contradictory to each other.

In this context, the RSS’s evolution as an ideological mentor to the BJP is quite instructive and without precedent in the history of building organisations of its kind. The manner in which the RSS allowed the BJS to merge with the Janata Party in the post-Emergency phase was indicative of its confidence in its swayamsevaks. When Deoras wrote a letter that freed swayamsevaks to follow their discretion in politics, he faced criticism. But an unfazed Deoras said that he was quite confident of his volunteers who would not be guided by a “letter”. Of course, as the socialist groups within the Janata Parivar pressed hard for BJS leaders to give up their allegiance to RSS, all BJS leaders, barring a few, came out of the Janata Party and floated the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) which appeared a seamless transition from the BJS. The BJP under the leadership of Atal Bihari Vajpayee followed “Gandhian socialism” which incorporated features of egalitarianism in sync with dominant political narrative.

What is particularly significant in the evolution of the RSS-BJP is the fact that the leadership of both the organisations was on the same page in using politics as instrument to empower social underdogs, particularly those belonging to most backward classes, scheduled castes and scheduled tribes. In the Sangh Parivar’s concept of Hindu Rashtra (Hindu nation), the inclusion of the marginalised sections of the Hindu society is an essential component of the nation-building project. The Modi government’s decision to overturn the supreme court order that diluted the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act must be seen as a sequel to this project. No doubt, such a project often comes at cross-purposes with the party’s substantial support base. But it would be naïve to undermine the capacity of the Sangh Parivar to navigate through these social landmines.

How Modi and RSS are on the same page

Among the many interpretations of RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s recent address is the supposed divergence between him and prime minister Modi, between the organisation and the government. But, if one looks without ideological blinkers, the opposite is the case – as both are turning out to be extra-sensitive to the dalit cause.

When the government takes the route of parliament to overturn a ruling of the supreme court, it is bound to be a defining moment. There was such a moment in the late 1980s when, in the Shah Bano episode, Rajiv Gandhi leveraged his majority in parliament to restore the sanctity of Muslim personal law which was diluted by the supreme court.

The move was seen as abject surrender of the Indian state to a section of Muslim clergy beholden to dogmas and obscurantism. It would not be wrong to say that the BJP owed its rise to this exposure of the Congress’s “pseudo-secularism” in the Shah Bano controversy. The then BJP president LK Advani recollects in his memoir, My Country My Life, that he had cautioned Rajiv Gandhi against this political misadventure.

Contrast the Shah Bano case with Modi’s decision to overturn the supreme court order that diluted the SC/ST Act, you will know the difference. There is an attempt to foment trouble on caste lines across the country. Yet, no political party is willing to be seen in the vanguard of the agitation against the apex court’s decision. The reason is not far to seek. On the other hand, the Sangh Parivar has been consistent in its endeavour to win over dalits for years on end. And there is a discernible pattern in these efforts.

On December 6, 1993, a year after the demolition of the Babri mosque, Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) supremo Ashok Singhal held a meeting with Hindu religious leaders of Ayodhya. The meeting assumed significance as for the first time, dalit icon BR Ambedkar was included in the pantheon of the Sangh Parivar’s “revered leaders”. The rise of the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and Samajwadi Party (BSP) as an effective counter to the Hindutva in Uttar Pradesh posed a grave challenge to the Sangh Parivar’s project. Hence the co-option of the assertive OBCs and dalits was the best option. This was followed by RSS-VHP leaders lining up outside the residence of ‘Dom Raja’ (the fabled king of the funeral ghat in Varanasi belonging to a scheduled caste) to have a meal with him. The spectacle was not only symbolic but also a determined move to align Hindutva with the assertion of the scheduled castes.

Modi’s thrust on winning over the scheduled castes is certainly not without design. Except for Uttar Pradesh, where the BSP is representative of the dalit assertion, this social block is still in a state of political flux. In large parts of the country, its political strength is often not channelised in a coherent manner. With the Congress withering away as an important political force, radicalisation of dalits in certain pockets often challenges social peace and harmony. Modi’s decision to overturn the supreme court decision on the SC/ST Act is part of the agenda of “Hindu socialism” which may be radical in its content but not in style.

Those who regard Modi’s pro-dalit stance as a charade would do well to remember that the BJP is the only party with national presence to have had a dalit, Bangaru Laxman, as its chief (not counting the one-off exception of Sitaram Kesri as well as the case of regional parties or parties formed on the basis of dalit identity). The project of elevating Laxman to the party’s top position came a cropper because of different reasons (he was seen accepting money in the Tehelka sting operation). But there is enough possibility of a dalit leader emerging as a Hindutva icon in future.

Given the fact that the RSS-BJP has been focusing substantially to co-opt dalits in its fold, the possibility of the emergence of a strong dalit leadership steeped in the values of the Sangh Parivar and aligned with the Hindutva ideology cannot be discounted. Consider the fact that the BJP has the largest contingent of SC/ST legislators in the country. In the Hindi heartland, the party has been winning the maximum number of seats reserved for SCs and STs. In states like Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand and Gujarat where tribals have significant presence, the party’s contingent of lawmakers includes this section too.

Those aware of Modi’s style of functioning would know that as party general secretary and strategist during his stint in Delhi in the late 1990s, Modi had always insisted on focusing more on non-traditional constituencies in the states under his watch. For instance, he let non-Jat leadership grow in Haryana while focused on tribals in the pre-bifurcation Madhya Pradesh. In Himachal Pradesh, he co-opted social sections falling outside the dominant Brahmin-Thakur leadership of the state. Over the years, his political experiments proved to be more successful than anticipated. In essence, Modi has never relied on a static social base for political support.

As the 2019 elections draw near, Modi’s outreach to scheduled castes and tribes must be seen as a determined plan to expand the party’s support base beyond its traditional social constituency. Needless to say, this effort may have to weather a rough storm given the fact that a section of traditionalists within the Sangh Parivar is still beholden to dogmas and social prejudices. Such resistances would be very feeble in the face of a profound change expected to be unleashed by dalit assertion within the Hindutva fold. If this happens, it would without doubt upend the traditional political leadership in the country and significantly conform to the Sangh Parivar’s idea of India.

ajay@governancenow.com

This essay was earlier published on FirstPost.com in a slightly different version.

(The article was published in October 15, 2018 edition)