Tribals come together to curb ecological degradation around Kanha National Park, hoping also to tackle their economic vulnerability

Incense sticks were lit. Ram Sahay Marawi, 70, was ready to break the coconut over the ground – an auspicious ritual before starting anything new. He along with fellow tribal villagers was worshipping grass seed balls that they had prepared mixing grass seeds in the mud. Everyone around waited for Marawi to finish the puja. Once he finished the ritual, everyone picked a few balls and scattered away to throw these balls in eight to nine hectares of the protected forest land of Khalaudi village which at present is barren.

Khalaudi village is 60 kilometres from Mandala in Madhya Pradesh and is dominated largely by the Gond tribe. Tribals are known for their dependence upon forest produce to fulfil their daily needs – be it getting woods, vegetables or medicinal plants – forest is their identity. The Gonds’ proximity to the Kanha National Park was their source of sustenance. But at present these people are dependent on the scarce vegetation in the buffer region, attached to the boundaries of Kanha.

“The situation has changed a lot over the years,” says Sahay. “We cannot go inside the jungle anymore but we need the same atmosphere on lands near our village. Therefore, in the limited land available we are trying to create a forest area to fulfil our requirements of woods, food, etc. Jungle humara phir se hara bhara ho jaaye [We want our forest to be green again],” he says. Khalaudi village is now gearing up to see a change on the forest land in their area. “We have planted only trees which are there inside the core area of the sanctuary and which is no longer available to us,” says Sahay.

“When we were kids, areas around Kanha’s buffer zone were covered with forest. Over the years it has reduced to barren. Now, we are trying to regenerate it growing grass and trees in the buffer zone. Once this is done, each one of us will benefit,” says Sampat Singh Tekam, president of Khalaudi’s village forest committee, under the forest department.

Khalaudi is inspired by Indravan, a forest village which was displaced from the Kanha sanctuary in 1977 and was resettled by the forest department. Gonds and Baigas (who are a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group) were given land for building hamlets and developing agriculture. However, a section of the forest protected land under this village was barren until 2012.

Indravan forest in 2012 (left), and in 2016 (right) (Photo courtesy: FES)

Today, trees like teak, saaj (Terminalia elliptica), dhawa (Anogeissus latifolia), bamboo, amla and baheda are in the growing stage. The grass grown on the land has helped villagers to feed their cattle especially when the vegetation is poor. About 15 hectares of forest land under this village has witnessed afforestation with more than 15,000 trees. Tribals living in adjacent Khalaudi have seen the transformation of Indravan in last five years.

Community ownership

The transformation of Indravan is result of community ownership by its tribals.

In Mandla district, nearly 70 percent of the land comes under the forest department. Out of this certain percentage of forest land is used as a common property resource. These do not fall under individual forest right but as community ownership, where people together manage these forests.

In 1988, the ministry of environment and forests recognised that forest management not only means conservation of the ecology but also meeting the needs of people. Therefore, in 1990 they introduced changes in the National Forest Policy and initiated Joint Forest Management (JFM) programme, involving local people in taking care of the forest.

Under this programme, a village works as a community with the help of the forest department. A non-governmental organisation works between the two. A particular village has to form a village forest committee (VFC) to take charge of the regeneration of forest. In return, they are entitled to consume forest produce and grasses.

However, for all these years tribals were unaware of these entitlements. Thus the village forest committee was inactive. However, in Indravan and Khalaudi, Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), an NGO, started working as an intermediary between tribal and forest department and made the VFC active in 2012.

Disturbances in the system

Since the 1990s, the Mandala region has seen degradation of forest and intensification of agriculture.

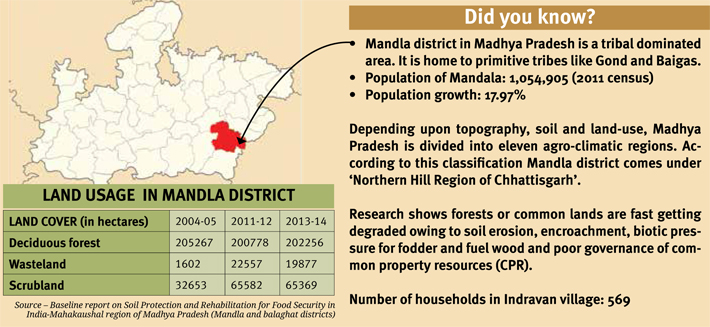

According to a report prepared by the FES in 2015, management of natural resources has been very poor. The deciduous forest has gone down from 2,05,267 hectares in 2004 to 2,02,256 hectares in 2014, while the scrubland (wasteland) has increased from 32,653 hectares to 65,369 hectares.

Degradation of land due to unsustainable land use has already resulted in the disappearance of about 30 percent of the water bodies in the district in one decade.

Almost 80 percent of the total population is tribal. They are all marginal farmers with small land-holdings. It is only during monsoons when they grow paddy and meet the consumption for the year. The overall income is very miniscule if they are able to sell a few kilos in the open market.

They are also dependent on the Mahatma Gandhi Employment Gurantee Act (MNREGA) to earn money. Many of them even seasonally migrate to earn money.

“We are now trying to live as per the government’s guidance. Do we have any other choice?” asks Sahay. “The amount of wood we used to collect for fuel has decreased now. Even our consumption of specific forest plants has gone down. Due to poor availability of forest resources we are no longer able to sell them in market. We are more dependent on the market. Expenditures are adding up but the source of income is limited,” he says.

In Bichhiya tehsil which has Indravan and Khalaudi villages, 52 percent households have an annual income less than Rs 1,000, 37 percent households fall in the category of Rs 10,000-25,000 while only 2.3 percent are in the Rs 25,000-50,0000 range. Approximately, half of the population here survives on Rs 700 per month, which makes them economically and socially vulnerable.

“No access to forest produce has affected us economically as well as socially. There was a time when we were least dependent on market to fulfil our food requirement. Now, we have to buy basic vegetables from the market. There are families who sell two to three kilos of rice or pulses to buy vegetables,” says Ghansaram Kusram, who in 1977 helped Indravan villagers during the displacement.

The changing ecological and social pattern has affected their life economically. The impact of which is seen on their food security and nutrition level. While children below five years of age are malnourished, 70 percent women suffer from anaemia.

“The forest land which we are trying to regenerate will not impact their income directly; rather it will have an indirect affect,” says Suhas K Hamsagar of FES who is working with villagers for last three years. “Even if they don’t sell grass and other minor forest produce in the market, they will use it personally. It will help in food security. In the long run tribals will also learn to work as a community for sustainable development of these forests.”

Common forest resources are important for food security, suggests a study done by FES in Godipokahri village of Dhenkanal district, Odisha. It is a tribal village dominated by Juang community, one of the primitive tribes of the region. The research shows that out of 60 items like mushrooms, leafy vegetables, fruits, nuts and tubers, which villagers collect from the forest, only five are sold in the open market. The remaining is consumed by families. Calculations reveal each household consumes forest produce worth Rs 2,638 per annum. The study says, in a typical household economy of the village where the household income is Rs 16,000 and the expenditure is Rs 18,000, the availability of forest produce for consumption plays a very significant role in reducing the vulnerability of the community as far as food requirement is concerned and also supplements nutritional requirements.

Indiscriminate use and state acquisition of forest land has resulted in poor availability of resources. Its impact on the local food system is a cause of worry as malnutrition is prevalent in the region. The National Family Health Survey-IV (2015-16) reveals that more than 50 percent children in Mandla are malnourished while 10 percent are severely malnourished. More than 70 percent women and 40 percent men are anemic. In such a situation, an effort to improve usage of community resource can be fruitful in future.

Forest and food security

- There is not enough evidence to prove that improved natural resources offer a long-term economic route out of poverty. But it is known that they provide safety for the poorest and are vital to their health.

- Forests have a significant contribution to food security. Studies shows that during the period of food scarcity, tubers collected from the forest meet the consumption requirements for about a month.

- In a study conducted by FES across 600 tribal households, 55 percent of the people identified a decline in the availability of minor forest produce as the most important reason for weakening the food security.

Taking note of the crisis emerging from the changes, villagers of Indravan, after decades of displacement, are now together ready to protect the land. For one year villagers took the responsibility to prevent it from animals and later Kamal Singh, a native of Indravan, was appointed a caretaker by the VFC.

“Protecting forest land without any fence is a difficult task. People in our village consciously took an effort to protect the land by not allowing their animals to come inside. In the last four years everyone equally played a role in the growth of these trees,” says Kamal Singh.

Villagers are happy that they can now feed their cattle properly. “Last year we got enough grass to feed our cattle. Earlier, as we had not enough fodder for them, we used to leave cattle for grazing. As the cattle are fed properly, there is an increased production of milk. But this is only for a specific season when grass is available. In years to come, our other forest-based requirements will also be fulfilled. Women will not have to go too far to collect wood,” says Shivram Marawi of Indravan.

(The story appears in the August 16-31, 2017 issue of Governance Now)