Gujarat was passing through a turbulent phase in the 1980s. The decade began middle class agitations against new reservation policies, and the caste friction turned communal under the watch of chief minister Madhavsinh Solanki, alienating majority of urban population on both counts. The ground was ripe for the BJP, but channelizing people’s aspirations into votes was difficult for the party. In the 1984 elections it managed to win only one seat from Gujarat.

That was when the RSS deputed a pracharak, barely in his mid-thirties, to the party. His first task: the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) elections of 1987. The party’s first electoral victory had come in the Rajkot civic body in 1982, and now it was the turn of the principal city of the state. The mood was in favour of the BJP, as the atmosphere of polarisation became pronounced. Amarsinh Chaudhary, who had replaced Solanki as chief minister after a long spell of rioting, did not help matters when he banned the Lord Jagannath Yatra, an annual ritual for over a century, supposedly to avoid any untoward incident.

Against the background of communal violence, this gave the impression that the state’s Congress government was bent on pandering to Muslims. The issue had been snowballing into a confrontation between Hindus and the government. The Sangh Parivar had thrown in its lot with the Hindus who were irate at the state’s decree. In peaceful years, the yatra gets a welcome in Muslim-dominated localities too. But things were different this time after a series of riots and emergence of a powerful Muslim underworld reigned over by the gangster Abdul Latif (who was to win from five AMC wards despite being jailed). This syndicate was seen as enjoying the patronage of successive Congress regimes.

In 1986, Modi was active in the functioning of the RSS-BJP and their affiliates, though he was still working behind the scenes. Tensions were mounting in the walled city as the yatra day approached. Policemen were posted all around the temple to prevent any move to take out the procession. Among the people, however, there was determination to defy the ban – even if it was not clear how.

When morning came, one of the elephants of the temple that lead the procession suddenly came out, surprising the security personnel. The chariots followed, and the rath yatra was on. Police personnel had little choice but to provide security to the yatra. There were, predictably, clashes as the procession passed through localities of mixed populations, but the ‘swayambhu yatra’, showed the majority a way to defy the Congress’s tendencies.

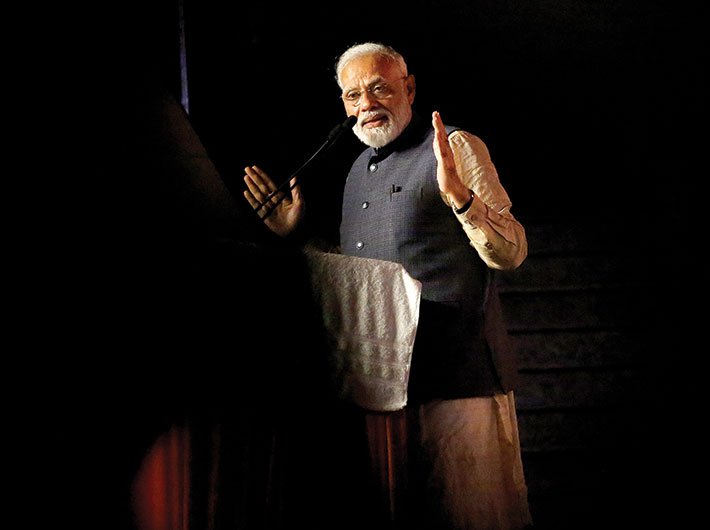

Few know that the planning behind this move came from Modi, though there has never been a credible acknowledgment. Soon, Chaudhary reportedly made inquiries, asking veteran BJP leader Keshubhai Patel, “Who is this Narendra Modi? I want to meet him.”

By the time he took charge of the AMC election in 1987, his first assignment after moving to the BJP, his name was becoming familiar to many in Ahmedabad and elsewhere in Gujarat though he confined himself to the backroom. The AMC poll victory is part of walled city folklore.

Like one of his heroes, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the AMC provided Modi the platform for learning the ways of administration and organization building that he was to replicate at the state and at the national level.

Modi’s methods of expanding the organisation was went beyond textbooks. As veteran BJP leader Harin Pathak recalls, the party knew only the traditional ways of holding rallies, making speeches, and mobilising people for an occasional event. The BJP was then seen as a party of Brahmin-Bania, the upper castes who do not have a substantial numerical strength in Gujarat. Modi’s strategy of co-opting marginalised social groups and what he termed as ‘neo-middle class’ in urban areas is unparalleled. This has formed the bedrock of the party’s unprecedented growth at the national level in recent times.

When he began, Modi was up against Madhavsinh Solanki’s formula of KHAM (Kshatriya, Harijan, Adivasi and Muslim). The Congress had won huge majority thanks to these four communities. Modi not only challenged KHAM but also replaced it with a rainbow alliance with a Hindutva hue. Initially, Patidars were the vanguard of this amalgam, but it later expanded to include tribals in large numbers. His strategic brilliance came to the fore soon after when he took over as the chief minister in 2001.

In Gandhinagar, Modi found himself in a tight spot after the Godhra carnage and ensuing riots, but he recovered quickly to take firm control of the perceptions. With the December 2002 assembly victory, he emerged as a popular leader in his own right. The win was largely attributed to communal polarization, but that was only one side of the story. In his ‘gaurav yatra’ across the state, he engendered hope among the people of restoring peace and Gujarati pride.

Right from day one of the second term, Modi wanted to go beyond the image of the ‘Hindu Hriday Samrat’. He had more to offer than Hindutva, especially in Gujarat. The formula he hit upon, later labelled as Moditva, was to champion development – which would include good governance with efficient administration, market-oriented reforms with welfare initiatives. Launching the Vibrant Gujarat investor summit in 2003 was the first concrete attempt in this direction, as it aimed to attract investments into Gujarat and perk up the image of the state.

Over the next five years, Modi worked to a plan. On one hand, there was no recurrence of riots. On the other hand, there were a plethora of initiatives that promised to scale up development work in Gujarat. He also started correcting the malaise that had beset the administration. For instance, he ensured 24x7 power supply all over the state by separating feeders for domestic and agricultural consumption. Since farmers were used to getting subsidised electricity, they rose up in revolt. Modi found a serious challenge to his authority from the farmers, led by vocal Patels. He used his persuasive and coercive skills as an administrator to force farmers to fall in line but not without a political cost. In the 2007 state assembly polls, a strong section of the Patels, egged on by a political lobby headed by a sulking Keshubhai Patel, opposed him with all its might.

The deft political manager that he is, Modi could foresee the problem and strategised in time to co-opt scheduled castes and tribes along with new-middle class voters. He tapped into the angst of the burgeoning new-middle class, which aspires for a better life. For this section, the assurance of round-the-clock electricity and supply of clean water was nothing short of a boon. This accretion of new social groups to the BJP’s fold significantly added to the party’s support base and offset the drifting away of the Patels. A senior officer told me that he had once tried to persuade Modi to shelve power sector reforms as it could affect his political prospects, but Modi had told him: “Go ahead and implement it. Don’t bother about the elections.”

In 2007, Modi won the polls, against all odds. He thus learnt that tough decisions are not always bad politics. A day after the Vibrant Gujarat Summit in 2011, Modi gave me a lengthy interview for Governance Now while driving to participate in the annual kite festival. Just after leaving Gandhinagar, he pointed towards some houses that had been demolished in order to widen the road. “This is our model of development which evokes support,” he said.

For Modi, the 2012 state assembly election was a cakewalk, as the Congress had since long given up any pretense of being in serious consideration at all in Gujarat.

There is a discernible pattern in Modi’s politics right from the AMC polls to the national level today. He has aligned his development work to popular approbation. At the same time, he is the first Indian politician – perhaps after Mahatma Gandhi – who has honed the skill of persuading people to face hardships brought on by his tough decisions. In 2014, he rode a popular wave of optimism against the backdrop of a government beset with corruption scandals. Unlike previous experiments of non-Congress governments at the national level, he focused on consolidating and rearranging his social support by taking up innovative initiatives.

It was not without reason that his first address to the nation from the ramparts of the Red Fort was touched upon cleanliness and changing social habits in rural India. He launched a massive drive to build toilets across the country, ignoring commentators who criticized the project. When he was asked if one needed to create infrastructure first before building toilets, Modi is said to have replied: “Let us not get into the chicken-and-egg dilemma. First build the toilet, the rest of the infrastructure would follow.” There is little doubt that there is deep social transformation in areas declared open-defecation free in rural India. Similarly, his insistence on opening a bank account for every Indian has profoundly impacted people’s attitudes towards personal economy. Also, the assured supply of electricity and gas in rural areas has significantly changed people’s lives and made them stakeholders in the continuance of the government.

While launching initiatives to reform the mindset at the larger level, Modi’s sustained spending on infrastructure projects across the country is intended to give fillip to economic growth and create jobs. He knows it better than most that the construction of highways, shopping malls and promise to build smart cities are not mere political assurances but also instruments to bring about a radical transformation in society.

People have continuously reposed faith in Modi’s vision, which explains his invincibility in every single major election he has faced since 2002. In the process, Modi is taking people along in his momentous experiment of changing the grammar of Indian politics: to him solely goes the credit for doing away with the old terminology of caste, community and poverty and introducing the new lexicon of good governance and development-for-all.

This metamorphosis is upsetting several old equations – and old mindsets. But for Modi, not much has changed since that civic body election way back in 1987.

(This article appears in the June 15, 2019 edition)