Many rural areas have become open-defecation free thanks to Swachh Bharat Mission (gramin), yet challenges remain

Globally, almost a billion people defecate in the open. There has been a 31 percent reduction in open defecation in India from 1990 to 2015, which alone represents 394 million people, said a UNICEF and WHO report ‘Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: 2015 Update and MDG Assessment’, which described the progress as “moderate”. Census 2011 confirmed that 49.8 percent of Indians defecate in the open. Five states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Odisha – account for nearly 50 percent of open defecation in the country.

On October 2, 2014, prime minister Narendra Modi launched the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) (Clean India Mission). It aims to accelerate the effort to achieve universal sanitation coverage, improve cleanliness and eliminate open defecation (OD) through two sub-missions: Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) for rural areas and Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban) for cities. It aims to achieve Swachh Bharat by 2019 to mark the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi.

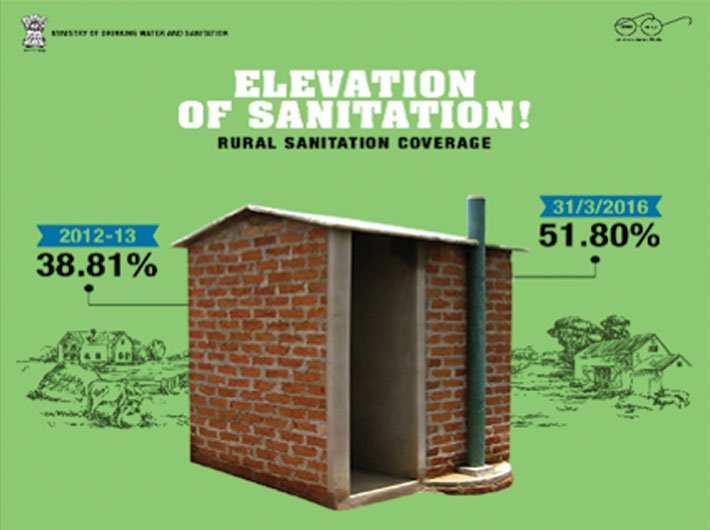

The report also notes that in India, there has been very little change over the last 20 years in reducing open defecation among the poor. According to data provided by the ministry of drinking water and sanitation (MDWS), 60 percent of India’s population in rural areas defecate in the open.

SBM places emphasis on awareness generation, triggering behaviour change and demand generation for sanitation facilities in houses, schools, aanganwadis, and places of community congregation and for solid and liquid waste management (SLWM) activities through community action and peer pressure. The programme focuses on installing people friendly, cost effective and ecologically safe technologies.

On the social front, the programme also seems mindful of the principle of equity and inclusion as emphasis has been placed on providing benefits to the elderly, disabled, women and children.

After more than a year of launching SBM(G), MDWS data on state-wise sanitation coverage shows that as on January 21, 2016, Sikkim and Kerala have more than 95 percent sanitation coverage whereas Bihar, Odisha and Jammu & Kashmir are drifting between 21 percent and 31 percent.

Since sanitation is a state subject, the SBM programme guidelines given by MDWS provide maximum freedom to states. States are free to choose any approach and technology while putting in certain minimum technical safeguards and financial best practices. The states have flexibility in implementation of SBM(G) through panchayati raj institutions (PRIs), civil society organisations (CSOs), community based organisations (CBOs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) etc. The states also have a flexibility to give incentives individually to households or to the village as a whole after the entire village becomes open-defecation free (ODF).

Implementation framework of each state has to include a road-map of activities covering three important phases: planning, implementation and sustainability.

Under the ministry guidelines of SBM(G), implementation is proposed with ‘district’ as the base unit, with the goal of creating ODF gram panchayats (GPs). Furthermore, the district collectors/magistrates or CEOs of zilla panchayats (ZP) are expected to lead the mission themselves so as to facilitate district-wide planning of the mission, optimum utilisation of resources and to give innovative approaches to solve the problem of OD.

Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin): Some best practices

Many success stories have emerged thanks to motivated district collectors/CEOs of zilla panchayats

Bikaner, Rajasthan: In April 2013, ‘Banko Bikano’ campaign was launched in Bikaner, Rajasthan, under the supervision of Arti Dogra, the district collector of Bikaner. The focus was on community-led and community-driven sanitation. The factors included convincing public representatives, engaging a dedicated team, finding a district coordinator and trying to erase memories of the past. The campaign branding used local language and customs. Strategies emphasised on intensive training and capacity building of stakeholders along with dedicated visits, follow-ups and meetings. The strategy was to focus on community-wide behaviour change rather than construction of toilets. The ODF GPs were recognised and rewarded under SLWM. There was also pro-active PRI involvement and different types of toilets were constructed as per the preferences and affordability of the community. Monitoring was done using a mobile app developed by water and sanitation programme (WSP). Twenty-one GPs claimed ODF status in the first month of the campaign.

Rajnandgaon, Chhattisgarh: The campaign ‘Swayamev Abhiyan’ was started by Priyanka Shukla, CEO, Zila Panchayat, in Rajnandgaon district of Chhattisgarh. The focus was on women. Swachh shapath (oath) was taken. Toilets were constructed and initiatives were taken by stakeholders. A penalty of Rs 500 was imposed for open defecation and the informer was paid Rs 100 as the reward. The CEO ensured that an ODF village gets high level of attention. As on August 2016, 71 villages were declared ODF in Rajnandgaon.

Pali, Rajasthan: The campaign ‘Phutro Pali’ (literally meaning ‘beautiful Pali’) was launched by Rohit Gupta, district collector of Pali district, Rajasthan. The campaign emphasised on team building, capacity building, monitoring and verification by nigrani samitis (monitoring committees) and involvement of PRIs. Households were motivated to make investments for toilets from their own resources and a few households were supported by the community. Payment of incentives was made on a fixed date every month. Within six months of launching the campaign, 23 GPs became ODF and 52,000 toilets were constructed.

Harda, Madhya Pradesh: In May 2014, the ‘Operation Malyudh’ (literally meaning ‘war against impurity’) was launched in Harda district of Madhya Pradesh. The campaign was led by CEO of ZP Shanmuga Mishra. In this campaign, offensive and embarrassing posters of OD were used to create feelings of insult and embarrassment. Workshops were organised, media was used under CLTS, training was given and eight teams of moderators were formed who were to pre-trigger, trigger and follow-up the work. Micro-planning was done for each household. Morning meetings were organised and WhatsApp groups were created. ODF status was celebrated by the villagers. The sparkle in one village led to peer pressure in neighbouring villages. Within three weeks of the launch of the campaign, Bichhapore became the first ODF panchayat. The outcome was seen in the behavioural change and not in the number of toilets constructed.

Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh: The campaign ‘Shahjahanpur ki zid’ was launched by Vijay Kiran Anand, district magistrate of Shahjahanpur district of Uttar Pradesh. Motivators from each block were selected for community approach. They were given whistles, torches, badges etc. with the theme “dabba pheko”. The SLWM model was experimented in 20 GPs with vermicompost units and biogas plants. Regular workshops for all stakeholders like pradhan, accredited social health activist (ASHA), auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) and block preraks were organised. Street plays, video vans and rallies were organised with an aim to mobilise people. Sanitation vans were sent to schools for cleaning, monitoring and campaigning. The campaign resulted in 210 GPs being declared ODF in three districts. And 70,000 individual household latrines (IHHL) were constructed, 450 school toilets were renovated and 3,200 vermicompost units were constructed.

Mandya, Karnataka: The campaign, ‘Mandya Experience’, was organised by Rohini Sindhuni, CEO, ZP of Mandya district of Karnataka. Two workshops were organised in each block and emphasis was on identification of PRI members without toilets. There was focus on exhaustive inclusion of all toilet-less households in the three-week campaign. A target of one lakh toilets was set in 232 GPs and 1,369 villages. Two toilets were to be constructed in each and every village in a time period of one week. 3,300 units were constructed and inaugurated by the elected representatives. Daily sanitation oath was taken in schools, street plays and dramas were organised, 50,000 BSNL mobile phones were given with a pre-recorded message on sanitation, whistle campaign and auto rickshaw campaign were launched with voice notes of the district minister.

Challenges to achieve SBM

The real challenges to achieve SBM in districts are many and some pertinent questions are:

- How are defunct toilets managed?

- How are the issues on SLWM addressed by the district administration?

- Whether the emphasis is both on achieving ODF and SLWM or only achieving ODF?

- Who is doing community-led total sanitation (CLTS)? How effective is it?

- What is done with the subsidy?

- Outreach to the poor for ODF

- Financial assistance to non-BPL (below poverty line) households for wide coverage and usage of toilets

- Issues in liquid waste disposal – drainage and treatment – availability of drainage network and disposal

- Lack of common treatment facility

- Availability of water to be ensured for using the toilets

- Operation and maintenance (O&M) of community toilets

- Attitudinal change necessary for achieving ODF

- Rationalising above poverty line (APL) and BPL status for providing toilets

In all the successful campaigns, there has been an emphasis on behavioural change, involvement of community and a uniform definition of ODF. The components of pre-triggering, triggering and village mapping in rural sanitation have a strong basis of community involvement and leads to a CLTS. It is important to emphasise on the community action plan, school triggering and learning from CLTS and shift in the approach in the Indian context.

Some lessons learnt from the various implementation strategies so far are: multi-pronged strategy – one size does not fit all; DM holds key to downward and upward coordination; elected representatives have permanent stakes; champions have multiplier effect; block as a unit yields faster results; focus on both individual and community toilets; campaign approach for behaviour change; availability of material; peer pressure through nigrani committee/water and sanitation committee and GP; PRI involvement and champions as facilitators; use of finance commission funds now available with panchayats, top-down and bottom-up approach and convergence in the district, district-block GP, team building, monitoring, recognition and facilitation.

This article is based on the inputs from Capacity Building Programme for District Collectors/Deputy Commissioners on Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin), organised by the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), New Delhi and sponsored by Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India.

Tiwari is a faculty member, rural development, Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), New Delhi.

(The article appears in the August 16-31, 2016 issue of Governance Now)