How NHAI is meeting the enormous challenge of digging long tunnels in mountains to bring Kashmir closer to the rest of India

Last breakfast at the headquarters of the Banihal-Qazigund tunnel project, where engineers are working round the clock to dig through two parallel 8.5-km tunnels, is served early in the morning to ensure that engineers and supervisors are at the site as the shift begins at 8 am.

As the sun comes up behind the mountains, oversize machines enter the tunnel from the two portals at Banihal and Qazigund sides. These ‘boomers’, with computerised controls, are specially designed for the job as it is too risky to deploy tunnel boring machines in the Himalayas. The battery of engineers keeps working at it round the clock, breaking only to change shifts.

“Meeting the engineering challenge is only a part of the difficulties. The tricky terrain makes transportation of the equipment and material to work site difficult and severe winter and snow fall restrict working time,” says P Satyanarayana, general manager of Navayuga Engineering Company that is constructing the tunnel.

To ensure uninterrupted work, the company has provided facilities for lodging and feeding supervisory staff as well as workers at the work site, he adds.

The expenses incurred on high technology and special facilities to the staff and workers have pushed up the productivity at the working site and clear signs of this were visible when this writer visited Banihal in January.

“We have dug through nearly 7.2 km of the 8.5-km tunnel and hope to achieve the breakthrough by blasting the last wall between Banihal and Qazigund by the year-end,” Satyanarayana says.

ALSO READ: "Our development spending has gone up by more than 50 percent" says Raghav Chandra, Chairman, NHAI

The tunnel aims to provide an alternative to the 2.5-km Jawahar tunnel through the Pir Panjal mountains under the Banihal pass that was commissioned in 1956 and remains closed for weeks in winter due to snow avalanches. It was designed for a traffic of 150 vehicles per day in either direction but more than half a century later more than 7,000 vehicles pass through it every day in both directions. Therefore, a wider and longer tunnel has been planned at a lower elevation.

Lower down the hills along the existing Jammu-Srinagar highway, engineers have already dug up a 9-km road tunnel between Chenani and Nashri and are now engaged in finishing the job by putting up supports and installing electrical, mechanical and communication equipment.

“The two-lane tunnel with a parallel intermediate lane escape tunnel will be the country’s first tunnel with an integrated tunnel control system (ITCS) of international standards, where the ventilation, fire control, signals, communication and electrical systems will be automatically actuated,” says SC Mittal, chief executive (implementation) of IL&FS Transportation Networks Ltd (ITNL), which has been engaged by the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI) as the contractor of this project.

(Chenani-Nashri south portal view)

The tunnel will shorten the existing 41-km highway through hilly terrain to an all-weather road of just 10.9 km. It will provide an alternative to the existing two-lane highway, which passes through steep mountain terrains and remains closed for 40 days a year due to bad weather. It will cross through the flyshoid geological formation in the Patnitop range of the Himalayas, skip the Nagroda bypass which truckers find difficult to negotiate due to its sharp and steep bends as well as the treacherous ‘Khooni Nala’ where shooting stones have frequently proved fatal for road users.

The Banihal-Qazigund and Chenani-Nashri tunnels are part of an ambitious plan of the NHAI to realign, restructure and redevelop the existing two-lane Jammu-Srinagar highway and construct a state-of-art four-lane highway between the summer and winter capitals of Jammu and Kashmir. The new four-lane highway will pass through a dozen tunnels, two dozen viaducts and 150 bridges, cutting down the existing distance of around 300 km by 60 km and the travel time by half.

“We are fast-tracking four of the six ongoing projects that were running behind due to the problems of logistics and land acquisition. Work on the two remaining stretches, which initially attracted few bidders due to engineers’ low estimates, has started after new contracts were awarded last September with upwardly revised cost estimates. All the projects are slated for completion by May 2019,” says NHAI chairman Raghav Chandra (see interview). It is not a routine exercise of widening and strengthening a highway – it is about erecting a new roadmap of advanced engineering structures, he is quick to point out.

The present route, which is part of NH-IA (now renumbered NH-44), started as the Banihal cart track by Maharaja Pratap Singh of what was then the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. It opened for traffic on May 1921 with the annual Darbar move from Srinagar to Jammu. Even after construction of the 2.5-km Jawahar tunnel and its development into a two-lane highway at heavy expenditure by the central government, it is treacherous and unreliable. Frequent snowfall during winters and landslides during monsoon and summers keep it blocked for weeks, cutting off the traffic between the Kashmir valley and the rest of India. That is one of the prime reasons for underdevelopment of the landlocked border state. Whenever the highway is blocked, the valley comes to a standstill, with no supplies of even essential commodities. Even at the best of times, it takes 10 to 12 hours of hazardous journey to commute between Jammu and Srinagar.

“When all the six projects are finished they will not only provide an alternative, safer, smoother and more fuel-efficient route of communication in this strategically important state but also reinforce the lifelines of economic growth in a region which is plagued by an acute infrastructure deficit, growing unemployment and stagnant agrarian economy,” Chandra points out.

The task is not easy as more than ten percent of the new road will pass through two big and ten small tunnels. As the world’s youngest mountain chains that are rising faster than any other, the Himalayas pose the most challenging ground conditions for construction engineers. They underline the famous words of the legendry pioneer of geological engineering, Josef Stini: “Nature is different everywhere and she does not follow the textbooks.”

With its complex geology, tunnelling in the Himalayas confronts engineers with diverse geological problems such as difficult terrain conditions, thrust zones, shear zones, folded rock sequence, in-situ stresses, rock cover, ingress of water, geothermal gradient, ingress of gases and a high level of seismicity. All these result in increased cost and extended completion period.

Indian engineers have demonstrated that they are capable of rising up to the challenge. After initially looking up to foreign experts they have learnt how to do it on their own. For the 9-km Chenani-Nashri tunnel, for instance, ITNL had initially contracted Leighton India – a subsidiary of Australia-based CIMIC Group, previously known as Leighton Holdings – for design and execution in 2010. However, following a financial dispute, it decided to undertake the project itself mid-way and its engineers finished excavation in a record time of 33 months.

Navayuga Engineering Company is constructing the Banihal tunnel with SMEC India, subsidiary of an Australian engineering and development company, as its independent consultant. Originally it was envisaged as a bi-directional, single-tube tunnel with two lanes. Later, it was revised to a uni-directional twin-tube tunnel design, which NHAI found better on technical and safety considerations.

“Tunneling through the mountains of Jammu and Kashmir is full of surprises and this project is more complex due to poor rock conditions that vary continuously through mudstone, siltstone and soft sandstone,” says Malcolm Rankin, SMEC’s project manager for underground works.

Using the new Austrian tunnel method (NATM) of sequential excavation and support system – considered the most advanced tunnelling technology available in the world – Indian engineers have shown that they can beat the clock despite restrictive working conditions.

In the completed Jammu-Udhampur section of the stretch, for instance, four tube tunnels have been opened for traffic in January this year. The old road passing through the Nandini wildlife sanctuary had sharp curves, hairpin bends and steep grades. The new alignment through a series of bridges and tunnels bypasses the curvy road and cuts the distance to 3.6 km.

While the full impact of the ongoing works will be visible only after completion of all the six projects, evidence of how this will transform road journey can be seen as one travels through these ‘Nandini tunnels’. Interconnected through a series of bridges and viaducts, they not only cut the travel time and fuel waste but also minimise disturbance to the flora and fauna of the Nandini wildlife sanctuary, a tranquil haven that is also home to several endangered species.

Earlier it took two-and-a-half hours to travel between Jammu and Udhampur, and the two-lane highway over the distance of 64 km passed through the lofty mountain terrain and was wrought with blind curves. It now takes 64 minutes to cover the distance. The earlier speed limits were in the region of 25 to 30 kmph. Engineered to have fewer curves, the new highway allows speeds of up to 60 kmph.

Clear signs of feverish activity are visible as one drives through the NHAI projects on the highway. Engineers and workers are working 24x7 to meet deadlines in the four ongoing projects (Jammu-Udhampur, Chenai-Nashri, Qazigund-Banihal and Banihal-Srinagar) that are running behind the schedule. Meanwhile, work on the two new projects on four-laning of Udhampur-Ramban and Ramban-Banihal stretches of the highway that were approved by the cabinet committee on economic affairs headed by the prime minister last September as the government-funded projects has started in record time.

Meeting the engineering challenges to push up infrastructure deficit in Jammu and Kashmir is no doubt significant. But the real significance of the government’s ambitious plan lies in deploying roads as tools for socio-economic development in a state whose people feel that they have been a getting a raw deal in the national development agenda of the successive union governments. Filling this infrastructure in sectors like road can prove to be the beginning of a larger political project for emotional integration of people and their mainstreaming in the national political ethos.

Early signs of this potential are visible during the process of road building itself. Over 90 percent of the workforce engaged by the NHAI concessionaires and contractors tasked with the job is from Jammu and Kashmir and this has substantially contributed to boost the local economy of the area.

While engaging local youth, the engineering companies involved have also taken special care to upgrade their skills by organising specialised training to BTech students from NIT Srinagar and other polytechnic institutes in the state. Local drivers have been provided specialised training on Volvo vehicles in Bengaluru and provided employment thereafter.

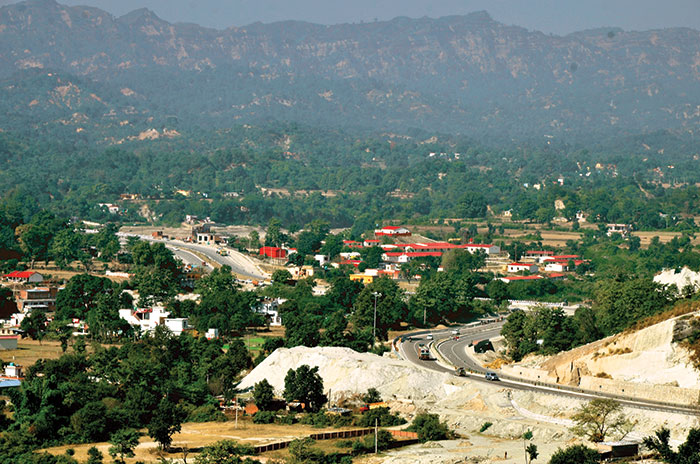

(Four-lane highway passing through Panjgrain village)

“Already over 10,000 local workers are engaged in ongoing projects and some of them are being given special training to upgrade their skill,” points out RP Singh, who heads NHAI’s regional office in Jammu and Kashmir. “They have not only gained valuable work experience but a rare opportunity to acquire new skills to improve their future prospects.”

However, one of the problems experienced by construction companies that worked on the Jammu-Srinagar highway was shortage of skilled manpower in the region. This forced them to recruit engineers and specialists from other parts of the country. The union and state governments could work out short- and long-term plans for training and education of local youth who can fulfil these tasks.

Apart from upgrading skills of local workforce, the construction companies engaged in road building have also undertaken many corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives in the areas of public health and sanitation, education and skill development, such as improving road works in neighbouring villages, boring wells and constructing toilets and installing water pipes. During winters, they provide power supply from their own generation to villagers.

The ongoing projects facilitating faster, safer and more economic all-weather connectivity between Jammu and Srinagar are bound to have a catalytic impact on integration of the backward economy of Jammu and Kashmir with the rest of India by spurring trade and commerce.

In Jammu and Kashmir, 49 percent of the workforce is employed in agriculture. The economy is also dependent on tourism. The state has export earnings from sale of handicraft items and food products. Road connectivity, therefore, plays a vital role in trade and commerce in this state.

The restructuring, realignment and four-laning of the Jammu-Srinagar highway have already spurred hectic road construction in the mountainous region. Roads form a critical component of the '80,000 crore development package for the state which prime minister Narendra Modi announced in November. In fact, more than half the amount, '42,611 crore, is dedicated to road and highway projects, including construction of the Zojila tunnel, semi-ring roads in Jammu and Srinagar, projects under Bharat Mala for better connectivity and upgradation of important highways.

Speedy implementation, however, is critical to translating these promises on the ground and, apart from facing engineering challenges, this will test the political will of the central and state governments. As the experience of ongoing projects on the Jammu-Srinagar highway shows, land acquisition remains a critical issue. Then there are social issues such as labour unrest, complaints about not enough local people being employed by construction firms and parity in their wages. These will have to be sorted out without waste of time and needless political meddling.

Fortunately, the current political environment is fortuitous. The party that rules at the centre also shares power in Jammu and Kashmir and few stakeholders in the state, including separatists, have openly opposed or obstructed development activities like road construction in region.

The remodelling of a new route between Jammu and Srinagar was conceived during the second innings of the UPA government but faced inordinate delays due to various reasons. There are indications that the Narendra Modi government and the Mehbooba Mufti government are serious about the project this time. The prime minister’s office is directly monitoring time-bound implementation of the projects and the state chief secretary is holding regular meetings of the state’s various agencies and NHAI officials to remove snags.

“We are committed to time-bound implementation of the projects,” the state’s minister for public works and parliamentary affairs Abdul Rehman Veeri has said.

Vajpeyi is a veteran journalist

(This article appears in the May 16-31, 2016 issue of Governance Now)