4.83 crore job-seekers registered. Only 3.39 lakh placed. That’s an efficiency rate of 0.7 percent. Is it time to retire our employment exchanges?

Over six decades ago, in 1954, six friends were walking past Agra’s iconic hotel, The Grand Imperial, when they noticed ‘Rojgar ka Daftar’ written in bold letters on a building on the opposite side of the road. This was then a highly regarded government placement agency, bustling with hundreds of job-seekers. All six of them, aged 17-19 years and fresh out of school, decided to enter the building. “It was good to see jobs being offered to people without discrimination or after seeking reference. For us, who were born before independence, this concept was new. Anybody could go and register. We did the same. I remember receiving a call for an interview in less than a month,” recalls 81-year-old Uttam Satsangi, who was one among the six friends.

Showing his faded interview call letter, which he keeps in a file with other important documents, Satsangi narrates how he took an examination, appeared for a personal interview, and had his documents verified – all in a single day. “They handed me the appointment letter at 11.30 in night,” he says. “My friends got placements in the next two or three months.” Satsangi was given the job of setting up a school in a village in Raisen district (Then part of the Bhopal state, created after independence out of the princely state of Bhopal, it was later merged into the new state of Madhya Pradesh.) He later went on to take other jobs, retiring as a senior official with the North Eastern Railway.

Cut to 2017. It is a dull but not an unusual day for 58-year-old Bharat Singh, sitting outside the same regional employment exchange office in Agra. Singh sells examination forms and pamphlets for various government jobs from his makeshift shop. Sitting on a stool behind a wooden platform, Singh is fanning off dust and flies from various forms. Since 1970, he has been the only regular visitor to this office, apart from the officials working inside. He inherited the shop from his father and remembers that, as a kid, he would help his father sell recruitment forms, revenue stamps and postal stamps. They had a typewriter on which his father would type out applications and fill out forms for job-seekers. Business was good then. But over the last week, he has not sold a single form. “It’s mostly like this now,” he says. “There’s no regular recruitment. Anyway, who gets a job from an employment exchange nowadays?”

Regional Employment Exchange office in Agra. Photos by Manoj Aligadi

Regional Employment Exchange office in Agra. Photos by Manoj Aligadi

Inside the main building of the office complex, there are seven-eight rooms. To the left of it stands an independent unit of two classrooms where SC-ST students are trained for taking selection tests for government jobs. The main building has a room occupied by a regional employment officer and a representative of the Uttar Pradesh government. (Employment exchanges are run by the state governments, in coordination with the union ministry of labour and employment.) In other rooms, there are statistical officers, employment officers, clerical staff. There are no files, but it’s not that the office has gone fully digital. For that matter, there’s only one functional computer there. Actually, hardly any work is getting done.

READ: Rebooting employment exchanges

The dullness inside the premises is at a time when 70,000 job seekers (including 8,000 women) have registered on its live register, not only from Agra but also from Mathura, Mainpuri and Firozabad. The live register displays the number of job-seekers on a particular day. In the first six months of this year, jobs have been found only for 111 job-seekers. One reason is that, unlike earlier, there are far fewer government recruitments. Lots of government jobs are being contracted, and young men and women are not interested in government jobs that are not permanent. Unlike earlier, employment exchanges hardly coordinate with the private sector to organise jobs for the jobless. Besides, says regional employment officer Pratibha Tripathi, “We need at least six assistant employment officers, but are managing with only one.” Across Uttar Pradesh, employment exchanges are short of some 100 assistant employment officers. Motivation levels are low; a proactive approach is lacking.

READ: Pronab Sen on jobless growth

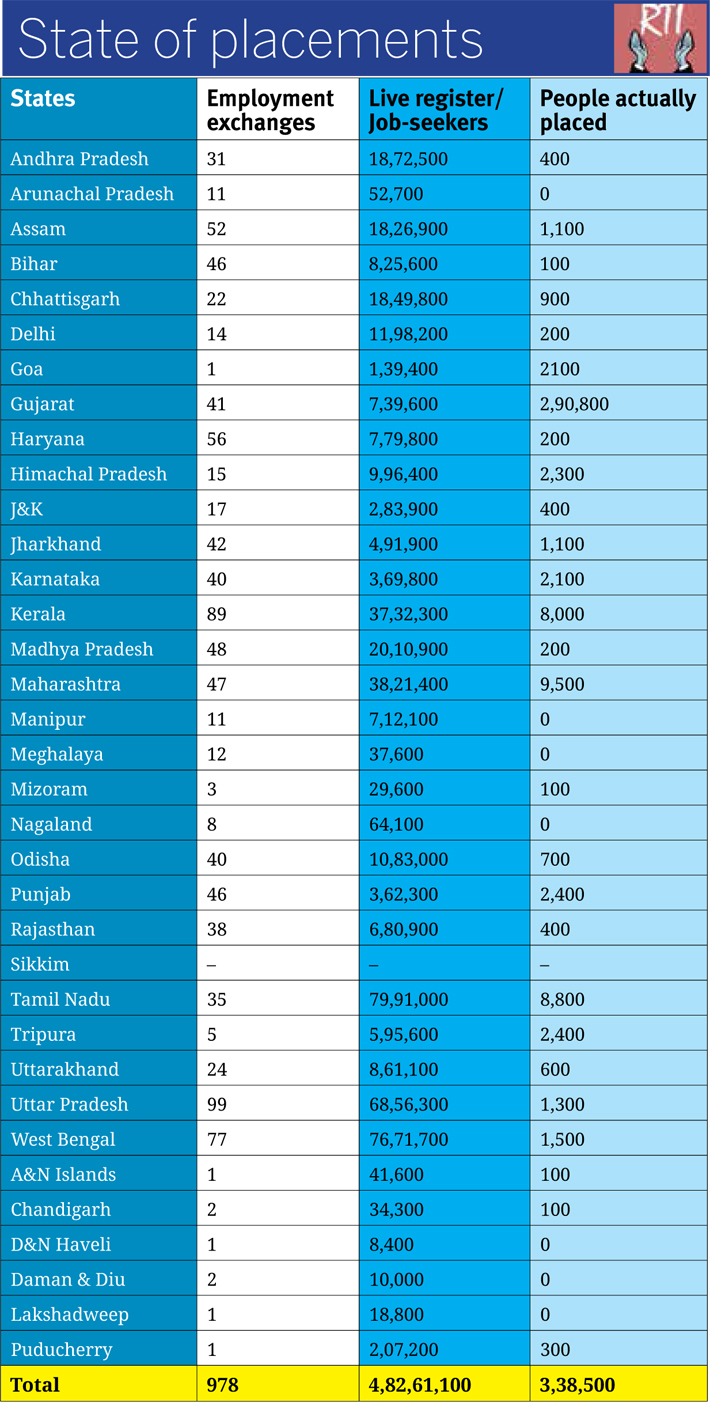

The numbers speak

There are 978 employment exchange offices across the country. But everywhere, it’s more or less the same story as at the Agra exchange. In reply to an RTI query by Governance Now, the union labour ministry stated that 4.83 crore job-seekers are on the live register, of which only 3.39 lakh have been able to find jobs. The placement percentage: 0.7 percent. Which means exployment exchanges, as an institution, are 99 percent inefficient. In his book, The Turn of the Tortoise, senior journalist TN Ninan picks out employment exchanges as an egregious example of government inefficiency: “The overheads per placement are five times the annual pay that the average placement offers. Talk of unproductive activity!”

Employment Exchange Statistics 2015

Number of employment exchanges: 978

Job seekers on live register: 4.8 crore

Placements: 3.39 lakh

Percentage placement: 0.7 percent

Vacancies notified: 7.6 lakh

The ratio of placements to registrations bears out the point he makes: according to replies received to RTI queries filed by Governance Now, in Delhi state, of the 11.98 lakh job seekers enrolled, only 200 have found jobs; in Tamil Nadu, where the registration is the highest, with 79.91 lakh job-seekers, approximately 8,800 people have found placement; in Uttar Pradesh, with registration of 68.56 lakh job-seekers, only 130 got placement. Gujarat stands out: out of 73.96 lakh job-seekers, 2.9 lakh have found placements. That’s only 3.92 percent, but it stands out because, in most other states, the placements run into less than one percent – just a few hundreds placed against the lakhs who have applied.

The labour ministry did not answer Governance Now’s RTI query on vacancies at employment exchanges and the budget for running each placement office and gave no explanation for not replying. When we made another application, the labour ministry directed us to approach the states. Meanwhile, a section of placement officers in different states with whom Governance Now spoke revealed that staff shortages are in the range of 60 percent. While they could not estimate the costs involved in running each exchange, they say it takes Rs 2 lakh to Rs 3 lakh to organise job fairs in tier-two or -three cities.

Down the drain

RTI replies reveal the immense inefficiency of our employment exchanges

We filed Right to Information requests with all states and union territories, seeking to know how much money they are spending on running their employment exchanges, the workforce, the vacancies in their offices, the job fairs organised and the amount spent on them. The figures were shocking. Meghalaya, for instance, said it spends Rs 4.26 crore every year running its 12 employment exchanges, but hasn’t organised any job fair 2014 onwards. There are 37,600 job-seekers registered with it, but the number of placements is zero! Uttar Pradesh, where the placement percentage is less than two percent, spends between Rs 15 lakh and Rs 88 lakh annually in running various employment offices. The state has organised 2,253 job fairs from 2014 onwards for which an amount over Rs 119 crore has been spent. Tripura has organised only one fair in three years. The state spent Rs 2,500. Gujarat, where the placement percentage is highest, has organised 3,984 job fairs. Tamil Nadu was able to organise 19 mega job fairs, but the state did not reveal information about small job fairs. The employment offices at IIT Roorkee and Lansdowne have not spent any amount on job fairs yet. The directorate of employment, New Delhi, has 290 vacant posts out of 357 sanctioned positions. The directorate is functioning with only one joint director, when there is a requirement for two. Also, the positions of deputy director, planning officer, psychologist and welfare officer are vacant. Odisha took the cake in replying. It cited nine reasons for rejecting Governance Now’s application, among them: a) “The information would cause unwarranted invasion of the privacy of any person” and b) “Your identity is not satisfactory [sic].” This when the same queries obtained detailed answers from states like Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Tamil Nadu.

“The employment exchange is an old industrial concept. In places like Delhi and Mumbai, there are private placement agencies and consultancies. The government has miserably failed. Manually-driven employment exchanges are a complete disaster. Labour market studies have shown that the role of the employment exchange is minimal,” says KR Shyam Sundar, a professor at Xavier’s Labour Research Institute, Jamshedpur. “Even I enrolled myself in an employment exchange some 20 years back. But I never received a single communication about vacancies or interviews.”

Going digital

Registration services in employment exchanges have gone online, but these portals are a far cry from private portals like Naukri.com and Monster India. There’s no employment exchange website in which you can browse through job openings by yourself. So job seekers are at the mercy of employment officers, who match up openings with candidates as they deem fit.

Even basic registration can be problematic. At the Agra exchange, for instance, Bindu Kumar, a job-seeker, was complaining that he’d paid a cybercafe owner to have his registration renewed, but it wasn’t showing up on the website. “This is our daily struggle,” says regional employment officer Pratibha Tripathi. “Job-seekers have very little knowledge about online processes, and we can’t always help everyone register.”

A training centre for SC/ST students on the Agra employment exchange campus

A training centre for SC/ST students on the Agra employment exchange campus

The labour ministry hopes to impove things by centralising employment exchanges across the country through the National Career Service (NCS) portal, launched in 2015. But it’s not linked to existing employment exchanges. Registration databases of all 978 exchanges should automatically have been made part of the NCS portal, but that has not happened. Job-seekers have to either register themselves afresh or register themselves using the registration number provided by the exchange with which they were originally registered. So far, there are 3.8 crore job-seekers registered on the NCS portal.

“The government has initiated NCS to support demand and supply. But an online platform like this has also failed as there is low internet penetration and most people who use affordable public platform for jobs don’t know how to use internet or make use of portals like NCS. That’s where the low-cost employment search mechanism fails,” says Sundar. The NCS, for instance, has opened its registration for local service providers like drivers, cooks, housemaids, gardeners, electricians and plumbers, much in the way apps like Urban Clap do. But it has received only about 4,500 applications.

The mela initiative

Job fairs are among the most hyped initiatives of employment exchanges. These events are aimed at bringing together job-seekers and recruiters from different sectors (public and private) on a single platform. While individual employment exchange offices organise job fairs in their own capacity, the centralised NCS has organised 552 job fairs, including four mega job fairs, during 2016-17. But they are doing little, if the placement figures are any indication.

READ: Inside a job fair

In July 2016, Arpit Mishra, who is from eastern Uttar Pradesh, attended a mega job fair in Noida. He was among the 2,000 aspirants who turned up. “Nearly half of the companies did not turn up. Most recruiters were not core companies but recruitment agencies and consultancies. Some even demanded money from candidates for training. Only two-three companies were directly recruiting, but that too for sales jobs,” says Mishra, an MBA. “I cleared the written and aptitude test and was told to receive communication about the interview in a week’s time. I never heard from them.”

Says Prof Sundar, “Sometimes, there are no job-seekers and sometimes no job providers. India is facing serious issue of job-search function and jobless growth as our labour market systems are not even well-tailored, forget about structuring.”

The way forward

Some experts claim that employment exchanges have huge potential but they need to be remodelled. “Employment exchanges need to become career centres that offer assessment, counselling, training, apprenticeships and jobs. They need to be brought into the 21st century with motivated staff, technology, and employer connectivity. The mobile phone revolution and Aadhaar offer opportunities for restructuring. But the most important change will come from performance management. Change will come only when punishment and reward are linked to the output of number of people placed and number of employers engaged,” says Manish Sabharwal, chairman, Teamlease Services, a staffing solutions company.

Prof Sundar agrees, “The important things for an employment exchange to function are good visibility, modernised system and high placement range. All three parameters are missing from our employment exchange offices. The government-run employment offices need serious restructuring. The government is paying a lot of attention to real estate but nothing on labour markets.”

Freebie effect

In 2012, there was a sudden jump in the number of registrations at employment exchange offices across Uttar Pradesh. As soon as the exit polls predicted a win for Samajwadi Party, people in huge numbers started thronging outside the employment offices. On an average, over 10,000 people registered at each office in Uttar Pradesh in one week. The reason: Akhilesh Yadav’s poll promise of distributing free laptops and employment doles to people registered at employment exchanges. According to the handbook of employment exchange statistics, the numbers of registration in the state increased to 4,409.8 thousands registrations from 466.5 thousand registrations previous year. Only three years after this, news reports said that 23 lakh people have applied for 368 posts of office peon in the UP secretariat. Among the applicants more than 200 hold doctorate degrees and over 22,000 have master’s degree in various disciplines. Over 1 lakh applicants have BTech and other professional qualifications.

swati@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the November 30, 2017 issue)