Graphic novel on the Sri Lankan conflict accomplishes sensitive task of bearing witness

Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the new president of Sri Lanka, won the November elections that were held amid continued polarization in the island nation. As defence secretary, he had led the government’s decisive fight against the LTTE rebels in 2009, in which most of the guerrilla leaders were killed. Thus ended the protracted war that began in the early 1980s.

When the British left and the nation became independent in 1948, the new government passed a citizenship law that virtually disenfranchised the minorities. Further, the government made Sinhala, the language of the majority, the official language in 1956, thus keeping near all minorities out of the administration. [For more background, check: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sri_Lankan_Civil_War]

Similar moves kept building a sense of statelessness among the minority Tamils. They formed several protest groups over decades, and by the 1980s only one of them was left – the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The Tigers chose the armed rebellion to right the wrongs. The Sri Lankan Army (SLA) was bound to retaliate in full force. Thus began the civil war, in which common people found themselves sandwiched between the two armed forces. Many Tamils in the north, though sympathetic to the cause of the LTTE, were reduced to being mere pawns, expendable. Over the decades, the international community, especially India, and the UN sought to intervene, but the best intentions don’t translate into efficient ground action in such exceptional circumstances.

The tragedy did not show any signs of ending, and tens of thousands of people in the north had no hope of escaping the theatre of war that their homeland had become and returning to normal life. The man-made disaster was complimented by a natural one in December 2004, when the tsunami hit the coast. Parts of the north, at times, did have a semblance of normal life – but the final phase of 2009 made their plight intolerable by any human standards.

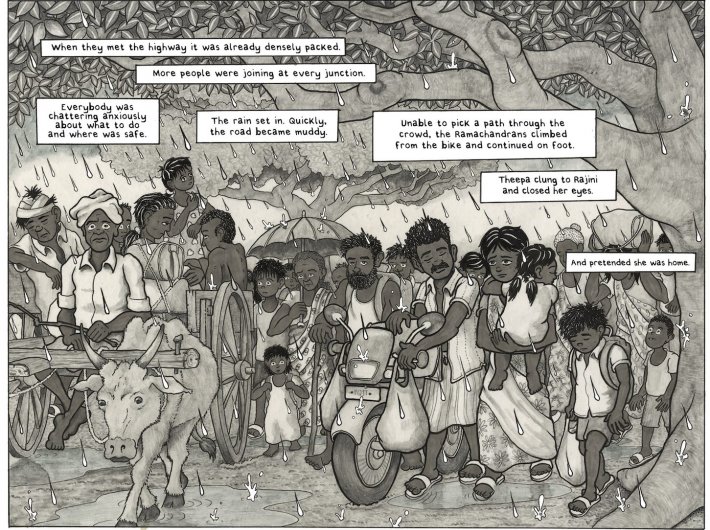

As tens of thousands of families rushed from one no-fire-zone to another at short notice, hordes moved on foot through jungles. The elderly, children or the injured alike forced to run for their life. They rested at night in temporary shelters, and found themselves in crossfires. Teenagers would be forcefully conscripted by one side and anybody could be picked up by the other side on suspicion. What they all went through is beyond words.

Yet words are all we have, and pictures can possibly help. Benjamin Dix, a senior fellow at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, has teamed up with artist Lindsay Pollock to produce an account of the tragedy in the form of a graphic novel. Dix had been there as a UN official, and had an “emotional return” in 2017. He is the founding director of the nonprofit PostiveNegatives, which produces ‘literary comics and animations that explore social and humanitarian issues’. Their latest work, ‘Vanni’ (Penguin, 2019), is an essential reading for our terrible time.

In in, we follow the turbulent life of two families, the Ramachandrans and the Cholagars, as their idyllic days in a coastal village, give way to the worst nightmares that keep going on and on. The fictional characters are composites of several survivors who “graciously entrusted us with their stories”, Dix writes in his afterword.

In the delicate job of bearing witness, Dix and Pollock have shown extraordinary sensitivity and empathy. The heartbreaking saga of the Ramachandrans and the Cholagars is rendered keeping focus on the human tragedy itself. The afterword takes up the job of supplementing the narrative with facts of the catastrophic irresponsibility.

“At the time of writing, independent investigations and justice has yet to be granted for crimes committed and many senior commanders from the SLA have been given international diplomatic positions,” Dix writes. “The international community has not only failed to investigate and hold to account, the crimes committed in Sri Lanka through the war, but instead Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales acting as head of the Commonwealth, celebrated Sri Lanka’s president Mahinda Rajapaksa by awarding him the title of Commonwealth Chairman-in-office on 15 November 2013.”

The war is over, the victors are in power, and there is no way to redress the injustice. The only way to counter the forgetting is keeping the memory alive, as many ‘memory activists’ from Milan Kundera to Masha Gessen have shown. ‘Vanni’ puts the reader face to face with Ramachandran, his life torn beyond recognition, and says: you can still help him, if you acknowledge his ordeal and chip in for justice wherever you may be.