Two books point to the seemingly insurmountable gap between what is and what ought to be as far as the Indian penal system is concerned

One of the most recurring motifs in the legal academy is the potential of travesty inherent in judicial systems. The prison statistic released by the national crime records bureau (NCRB) for 2013 bears solemn testimony to this fact. India is still governed by the Prisons Act of 1894 in which imprisonment seems to be the raison d’etre of the penal system. With a peculiar mix of colonial laws combined with the malaise of rampant corruption and stark economic inequality, India has one of the worst undertrial-prisoner ratios.

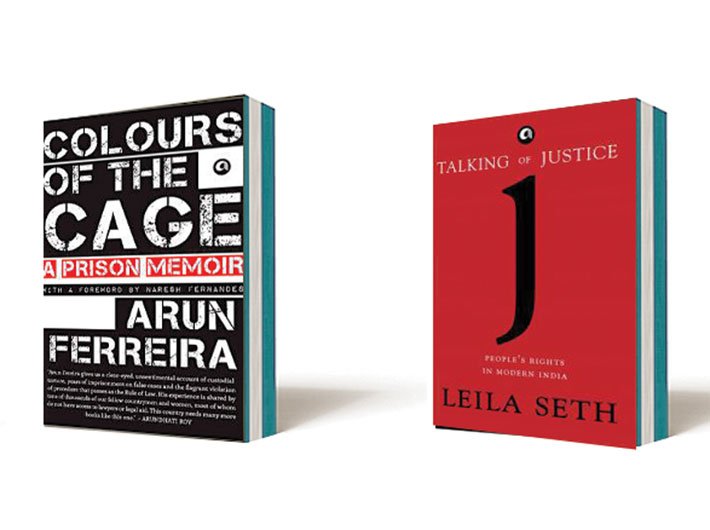

Against the backdrop of the NCRB numbers, two recently published books make for particularly interesting reading, not least for who the authors are. Colours of the Cage—A Prison Memoir is written by Arun Ferreira, an undertrial who was in prison for almost five years before being acquitted of all charges, and Talking of Justice —People’s Rights in Modern India by Leila Seth, the first woman to become the chief justice of a high court in India. Despite the fact that the authors lie at the opposite ends of the legal spectrum, they talk of (in)justice and both agree that something is terribly amiss.

As the title suggests, Colours of the Cage, is an account of four years and eight months that Ferreira spent behind bars. Born and raised in the posh suburb of Bandra in Mumbai, Ferreira was an activist since his student days. With former prime minister Manmohan Singh branding the Naxals as “India’s greatest internal security threat”, there was a crackdown on activists, media and anyone perceived to be sympathetic to the Maoist cause. Ferreira was one of them. He was arrested on May 7, 2007.

Ferreira’s experience in prison is essentially a narration of the economy of suspended rights – from the denial of access to a prisoner’s manual (which is his basic right), to the (illegal) act of forcible narco-analysis and brain mapping tests, the highly risky and callous administration of the truth serum (mind-altering drugs that are said to render a person incapable of lying) to waterboarding and administration of petrol in the prisoner’s rectum – the ‘due process of law’ having been given a long leave of absence. It would be two years before charges could be framed against the accused, including Ferreira. He writes, “Through this protracted process, the judges could, if they chose, allow the accused to be released on bail. But I was denied this luxury in every case in which I was implicated.”

However, the one thing that moved with much alacrity was his identification number in prison—from hauladi (mispronunciation of havalati or detainee) number 3479 in 2007, Ferreira graduated to number 5 in 2011.

The Indian prisons are bursting at the seams in spite of guidelines to the contrary. Ferreira says, “It is normal for three inmates to sleep in a place for one as prescribed by the prison manuals.” This is not surprising though. The author says of the Nagpur prison that “majority of the inmates, whether they were alleged Naxalites or not, did not fit any recognisable definition of criminal.”

The NCRB data of 2013 reveals that Indian prisons have more than 2.5 lakh undertrials that make for 65% of prisoners. The northeastern states of Meghalaya, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh are particularly worse off. For the northern states, Bihar has 4,480 convicts to 26,609 undertrials, Uttar Pradesh has 25,310 convicts and 58,100 undertrials and Delhi has 3,388 convicts against 10,154 undertrials. In 2012-13, the number of convicts rose by 1.4%, but the number of undertrials went up by 9.3%.

The data also reveals that Muslims are overrepresented as undertrials – a fact corroborated by Ferreira in his book. Ironically, however, Muslim festivals in prison are important events. Ferreira writes, “The cries of the azaan and the sharing of iftaar delicacies lend a festive air even to the anda (egg-shaped high-security cell where dreaded criminals are kept).”

The author also effectively brings out the ludicrousness of some laws of the country. He was taken aback when a fellow inmate named Asghar Kadar Shaikh, convicted for blasts on a rail track in Mumbai, explained to him that inmates, whether convicted or on trial, were barred from voting under the Representation of the People Act, 1951, even as it allowed undertrials and those convicted under certain offences with sentences less than two years to contest elections. Shaikh rather astutely observed that the prisoners need to become a vote-bank; “politicians would then value our voice and improve prison conditions”.

The poignancy is interspersed with liberal doses of humour. Since undertrials often spent the hours between 8.30 am and 6.30 pm on their way to court and back, defying all notions of rationality, their meal times ran thus: Tea at 7 am, breakfast at 7.30 am, lunch at 8 am. Since the prison manual lays down exactly what an undertrial must consume, the authorities fulfil their obligation through this creative and most novel arrangement.

Observing the brutality rampant in prison life, Ferreira states that though Maharashtra has the second highest inmate death rate in the country – NCRB recorded 102 deaths in 2010 – not a single one was attributed to negligence or excesses by prison personnel. In the NCRB 2013 data, out of 51,120 complaints received against police personnel, more than half (26,640) were found unsubstantiated. Only 655 judicial inquiries were instituted and 799 police personnel charge-sheeted.

With an unpretentious style, Colours of the Cage is an emotive tale of a wronged person sans the baggage of drama.

Talking of Justice is Leila Seth’s third book after her autobiography On Balance and a book for children, We, The Children of India: The Preamble to Our Constitution. Seth’s book is imbued with her humanity as well as her rectitude of judgment. As a member of the justice Verma committee that was constituted after the infamous Delhi gangrape of December 2012, Seth along with the rest of the panel suggested to the government to make marital rape a crime, a recommendation which was not accepted by the government. She cogently argues: “Is a woman to be bound by the feudal fiction of irrevocable consent the moment she takes the marriage vows?” She is also a vociferous supporter of making the crime of rape gender neutral for both the perpetrator and the victim. This recommendation was also shot down by the government. Given the patriarchal nature of judgments by the lower as well as higher judiciary, it is refreshing to observe such fair logic being employed throughout the text, whether it is for the rights of widows, children or the LGBT community.

The book has a fair amount of interesting data and facts to capture the attention of the reader: the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child has been ratified by all countries except Somalia and the US, studies by UN Population Fund say if the present trend of discrimination against the girl child continues, between 2011 and 2020, more than 140 million girls will become child brides and that most prisoners in Rio de Janeiro are in their cells for 23 hours a day.

The chapters on Prisoners’ Rights and Widows’ Rights are especially well-written. Given her experience from the one-member committee – Justice Leila Seth Commission of Enquiry – to probe the custodial death of the famous cashew baron, Rajan Pillai, Seth has lucidly delineated a brief history of prisons in India, the malignant problems ailing them (as corroborated by Ferreira in his book) and some practical and humane reforms to the prison system in India. Seth rightly argues that “prison is for reformation, not retribution.”

Talking of Justice includes most of the well-known cases of discrimination and cruelty: the Bhanwari Devi rape case, Vishaka vs. the State of Rajasthan, Shah Bano Begum vs Others, the Roop Kanwar case, etc. However, Seth could perhaps have employed as examples some not-so-famous cases, highlighting more subtle but equally grave forms of discrimination. The readers as such could have benefitted much from her breadth of scholarship and legal reasoning.

Her style is direct and accessible – it should in fact be a ‘101 book’ for a wide range of subjects from rights of undertrials to judicial administration to uniform civil code to issues affecting the girl child. One almost wishes that Seth had written this comprehensive book in 2007 so Ferreira could know exactly what his rights were then.

Reading the two books in quick succession, one is left feeling overwhelmed by the seemingly insurmountable gap between what is and what ought to be as far as the Indian penal system is concerned. Ferreira in Colours of the Cage has used pseudonyms for all his abusers thus protecting the identity of those who made him the most vulnerable. He explains that it is the System, not individuals, that is to be blamed. One may or may not agree with such reificatory logic but it is in these acts of humanity where justice still thrives.