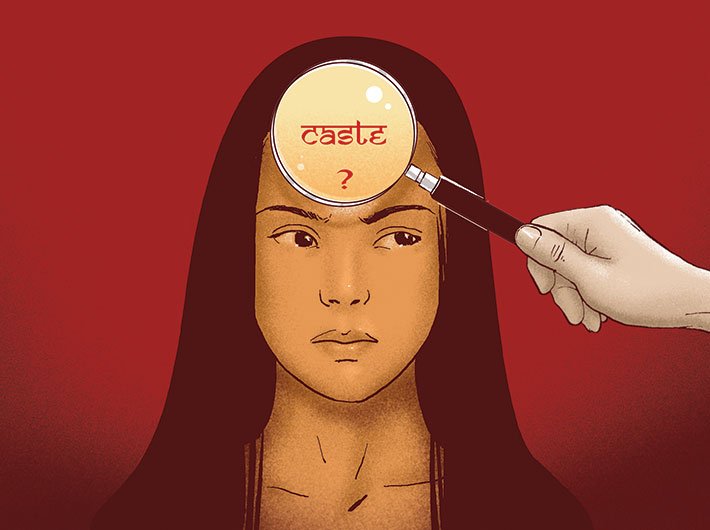

When Hima Das won gold in the 400 metres sprint at the IAAF World U-20 Championship in Tampere, Indians demonstrated once again what’s on their minds the most – caste. On her day of glory, the top Google prompt for her name was “Hima Das caste”. The same had happened with wrestler Sakshi Malik and badminton player PV Sindhu on the days they won their Olympic medals. People seemed hardly interested in what might directly contribute to these sportspersons’ prowess, such as their height. Or how Das’s timing compares with the world record. And the most searches about their caste, not surprisingly, came from the regions to which they belonged: Assam and Bengal for Das, Haryana, Delhi and Rajasthan for Malik, and Andhra Pradesh and Telangana for Sindhu.

We might think such prurient curiosity about caste is shocking, but as Indians, we all know there is nothing surprising. Caste is a complex sub-continental phenomenon, and it can be exasperating to explain it to a westerner. For there are castes within castes, sub-castes within sub-castes, and even among the savarnas, there are regional and linguistic divisions and sub-divisions. Add to that the long and appalling history of the oppression of dalits, which continues to this day, fed by a reactionary aggression against the quota benefits created by law for their empowerment, and we have a situation in which any debate is fraught and any argument open to accusations of bias. While caste and consciousness of caste is a fact of life in India, there can be no accepting it in the way we can accept regional or linguistic pride. It isn’t as if casteism in India is confined to Hinduism; casteism is known to operate even in other religions on the basis of which Hindu caste a family belonged to before it converted, even if that may have happened generations ago.

Reservation in professional and other courses and job quotas have not helped improve the lot of the ‘ground down’ dalits. In schools and colleges, they find themselves unable to cope, isolated and sometimes ignored. Studies have shown that as first-time job applicants, they lack confidence right from the beginning for reasons ranging from how they look or dress to their inability to speak English. While they do have a presence in government jobs, it’s not too often that they rise to the top echelons. In the private or corporate sector, they hardly have a presence. Even in the media, they are rarely seen in middle- or high-level positions. Clearly, biases have been at work that have prevented them from even getting an education that turns them into confident professionals.

Dr BR Ambedkar put it this way: “Turn in any direction you like, caste is the monster that crosses your path. You cannot have political reform, you cannot have economic reform, unless you kill this monster.” For casteism to fade away, caste consciousness must fade away. This is unlikely to happen soon. For what have we really done to nudge people to un-think caste? On the contrary, at every street corner we can find caste-based organisations, matrimonial ads are micro-classified on the basis of region, language, and caste, and we have political parties named after high socialist ideals but in fact predominantly representing a caste.

So how does one slay the monster, especially one that has thrived more than 70 years after independence, in a country that promises, at least in theory, equal opportunities for all? In his famous undelivered speech on the annihilation of caste, Ambedkar – while averring that he was going to have nothing do with Hinduism – said that ending the endogamy that perpetuates caste would be the only way for caste to die out.

In fact, it is the only way in which casteism will eventually die out, if at all – through a return to exogamy, which prevailed for ages before a consolidation of caste identities through proscription of marriage outside one’s caste. The claims to caste purity – scientifically improbable, given the millennia of intermingling of peoples before caste consolidated itself – are unfounded. While there is a scientific case for inter-caste marriages – hybrid vigour – it is not an idea that has caught on in India. Probably it never will. Even in educated, cosmopolitan groups, the inter-caste marriages are usually among savarnas.

The other big idea that could work towards eradicating caste is to end the association of caste with occupation. But like inter-caste marriage among savarnas, this is happening only among certain professions. No one thinks, for example, about a surgeon being, let us say, a vegetarian Brahmin, who should, by accepted norms, flinch at cutting open human flesh. Or a cadaver, if he’s a forensic expert. Nor for that matter does anyone ask questions about a Patel or a Vaishya doctor, lawyer or teacher.

Where it would really matter, perhaps, is in the two occupations at the opposite ends of the spectrum: priesthood and scavenging. As far as the first goes, beginnings have been made in south India. Tamil Nadu, under a DMK government, decided that non-Brahmins, including dalits, would be trained to perform priestly functions and be open for selection as priests at the major temples. However, the supreme court ruled, three years ago, that temples would be allowed to follow their own agamas, or customs, in the matter of selecting their priests. In Kerala though, the Devaswom Board, which governs temple appointments, last year recommended the appointment of 36 non-Brahmins, among them a handful of dalits, as priests. There were whimpers of protest – that one of the priests so appointed was neglecting his duties – but these died out soon. A progressive step has indeed been taken and it’s worth repeating in other states though storms of protest can be anticipated.

Now for scavenging. In 2016, an NGO in Ahmedabad stirred up things with a job ad for the post of sweeper, saying preference would be given to candidates from the Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaniya, Patel, Jain, Saiyad, Pathan, Syrian Christian, and Parsi communities. This is the sort of provocation society needs from time to time to change age-old modes of thinking. While it is unlikely that anyone from those communities would have applied anyway, given India’s ugly reality of caste, the reaction was predictable. Protests were held by at least one Muslim group and groups representing many Hindu castes. The NGO’s office was gheraoed and vandalised.

It was taken as an affront that it could even be suggested that upper caste Hindus (and Muslims groups who claim to be direct descendants of the Prophet) might ever consider taking up the job of a sweeper. No matter that this was in Gujarat, land of the Mahatma, who, though a Vaishya born, would clean out the toilets in his ashrams and encourage other upper-caste residents to do the same. For the caste taboo around cleaning up to end, along with the exploitation that goes with it, activists such as Magsaysay award winner Bezwada Wilson have suggested that these activities be fully mechanised. A beginning could be made to end manual scavenging and the practice of sending men down into sewers to unblock them. It should be the government’s priority to find funds for the mechanisation of these processes, maybe as an important component of the Swachh Bharat mission.

The trouble, however, with provocative measures like having dalit priests or seeking high-caste sweepers is that in the absence of an even-handed application to all religions, they will be seen as a heretical attack on Hinduism alone. For segregation of a kind is also practised in churches, gurudwaras, and mosques too. Vote-bank and appeasement politics have generally meant an attitude of “leave them alone”. And so there has been no real reform.

Coda: The cross-departmental co-ordinator of the Swachh Bharat mission, a former IAS officer, has often worked to break the scavenging taboo, holding up manure made from cesspits saying, “This is gold!” When Governance Now profiled him, he told us of a village near Warangal where he lifted manure from dried cesspits to set an example. In that south Indian village, his name and surname would have given away his caste. Maybe not to all Indians. Curious to know who he is? Do Google for his name. But not for his caste, please.

sbeaswaran@governancenow.com

(The column appears in the August 15, 2018 issue)