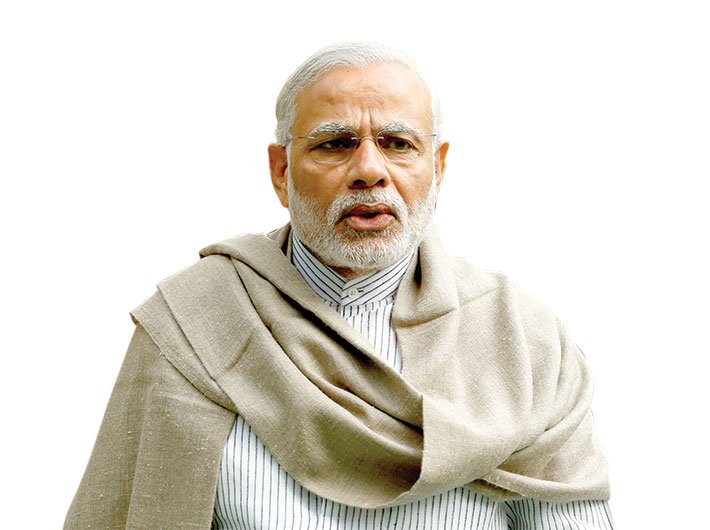

Though Modi’s popularity remains largely intact, the newfound opposition unity can pose a grave threat in 2019

When numbers forced prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee to demit office on the thirteenth day, he delivered a memorable speech in the Lok Sabha, ending on a trademark wave of his hand and saying that they were going to the president to submit their resignation. It was an extraordinary day in the history of the Lok Sabha, marked by impassioned debate, but the most impressive intervention came from Vajpayee’s immediate predecessor, PV Narasimha Rao.

In his role as the leader of opposition, Rao enumerated the BJP’s limitations, punctuating his speech with the wittiest remarks. Turning to Murli Manohar Joshi, for example, he asked, “Joshi-ji, vo aap kya kahte hain, ‘Bharatiya matlab Hindu’ (Joshi-ji, you say being Indian is equal to being Hindu)”. An unsuspecting Joshi bit the bait and responded in affirmation. “So it means the Indian Penal Code should be called the Hindu penal code,” he said amidst peals of laughter from members.

In essence, Rao’s argument was that the BJP-led government was in minority because it did not represent India – the nation was rather represented by the rest, the opposition. This was as much due to the party’s ideology of Hindutva, as due to the allied notion of a strong leadership – in the form of LK Advani, though Vajpayee had a moderate image.

Shrewd politician that he was, Rao knew too well that the perception of a strong leader in India engenders unbridled hubris and ultimately promotes alienation. In a way, he was a victim of this syndrome in his five-year regime which saw cunning at its worst. In 1996, Rao, arguably one of the most influential prime ministers of India, was isolated even within his own party. But he was perspicacious enough to caution Vajpayee that the paradigm of strong leadership can take the BJP only up to a point, and it would be easily defeated if its rivals joined hands.

Needless to say, two years later in 1998, when the BJP returned to power and formed a stable government, it was thanks to its widespread acceptability backed by a rainbow coalition.

Though much has changed in politics since 1996, Rao’s words are relevant again at this juncture, when a majority of the BJP’s

rivals literally joined hands in Karnataka exactly a year ahead of the scheduled general elections.

It would be rather naïve to dismiss as inconsequential the show of strength by the Congress and the regional leaders and in Bengaluru on the day when HD Kumaraswamy took oath as chief minister. If one looks at the spectrum of leaders gathered there, it is clear that the Congress is willing to cede its political space to accommodate regional satraps in order to forge an anti-Modi coalition at the national level.

The political alignment in Bengaluru, of course, confirms the BJP’s principal position in Indian politics. But is that enough for it to win the 2019 elections? Party president Amit Shah has said they are aiming for a 50 percent vote share next year – far higher than what was achieved in 2014 which itself was a best-case scenario. If Shah’s dream comes true, the BJP will come to resemble the Communist Party of China (CPC), which it has overtaken in terms of the number of members when it claims to be the largest political party in the world. Then India can also come to resemble China. But can it happen? The answer will be predictably negative.

There have been times in the life of this nation when people become impatient with the slowness of democratic processes, and pine for a strong leader, an authoritarian regime and quick way out of the travails of mis-governance. But not for long. Advani fought the 2009 elections on the single plank of ‘a decisive leader’ – as against an outright weak prime minister (and Manmohan Singh never claimed to be otherwise). The BJP lost.

This is not peculiar to India. At historic turns, many nations have exhibited a strong urge for a benevolent dictator who would solve all their problems. After all, as British political scientist Archie Brown has pointed out, have we ever heard for any nation that what it really needs is a weak leader?

Brown, in his The Myth of a Strong Leader (2014), writes, “The central misconception, which I set out to expose, is the notion that strong leaders in the conventional sense of leaders who get their way, dominate their colleagues, and concentrate decision-making in their hands, are the most successful and admirable. While some leaders who come into that category emerge more positively than negatively, in general huge power amassed by an individual leader paves the way for important errors at best and disaster and massive bloodshed at worst.”

He believes that in a democratic setup, such leaders “can do far less damage, precisely because there are constraints upon their power from outside government. It is, nevertheless, an illusion – and one as dangerous as it is widespread – that in contemporary democracies the more a leader dominates his or her political party and Cabinet, the greater the leader. A more collegial style of leadership is too often characterized as a weakness, the advantages of a more collective political leadership too commonly overlooked.”

His conclusion is, “Effective government is necessary everywhere. But process matters.” It is a dictum, it seems, Indian masses have learnt.

By temperament, the impression of a powerful leader looks an attractive proposition in a fractured polity but soon triggers a counter-reaction at the social level. With the exception of Jawaharlal Nehru, every powerful leader has passed through this ordeal. Take for instance Indira Gandhi whose victory in the Bangladesh war made even her rivals hail her as an avatar of Goddess Durga, and yet she soon lost badly in the face of a united opposition. Her son, Rajiv Gandhi, was a strong leader though not by temperament but due to the historic majority. By the fourth year, his halo of invincibility was replaced by utter vulnerability. Again, a united opposition was the recurring theme.

For contrast, consider the other model of leadership. Rao and Vajpayee never projected themselves as the leaders of the ‘my way or highway’ school. They were not reckoned as powerful as Indira, Rajiv or Modi. Numbers too taught them the coalition dharma of adjustment and conciliation. They managed contradictions in a Machiavellian manner. They went on to complete their full terms. Compared to these two leaders, Manmohan Singh, though he served two terms, could never rank himself a leader per se. Since he never countered the impression of being a weak prime minister, he was an anti-thesis of a strong political personality.

In hindsight, then, Modi’s mighty majority was as much a boon as a bane. It fueled his take-no-prisoner attitude, and a significantly large section of people still continue to support his no-nonsense style of governance. But, the paradox of power is coming to the fore. Partners are leaving the BJP-led coalition, and rivals are ganging up. The fact is that both are doing so not for some alleged ethical reasons but for the petty reason of their own survival, but that is no solace for the BJP. When natural enemies like Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party come together, it is obvious that their interests are bound to clash sooner than later, but by then it would have served its purpose of defeating the BJP. The internal contradictions of any such platform built solely over the plank of defeating X will play out as they did at the national level in 1979-80 and 1990-91, but that would come after the defeat of X, as witnessed in the Lok Sabha by-elections from Uttar Pradesh earlier this year.

One year, as the cliché goes, is a long time in politics, and Modi, as even his rivals acknowledge, is a master of the art of reinventing himself. It is possible that when he faces the electorate again, he would have changed himself to suit a more modest mandate. It is also possible he will come up with some out-of-box idea that will shock his rivals and awe the rest. Then again, one must hedge one’s bets.

ajay@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the June 15, 2018 issue)