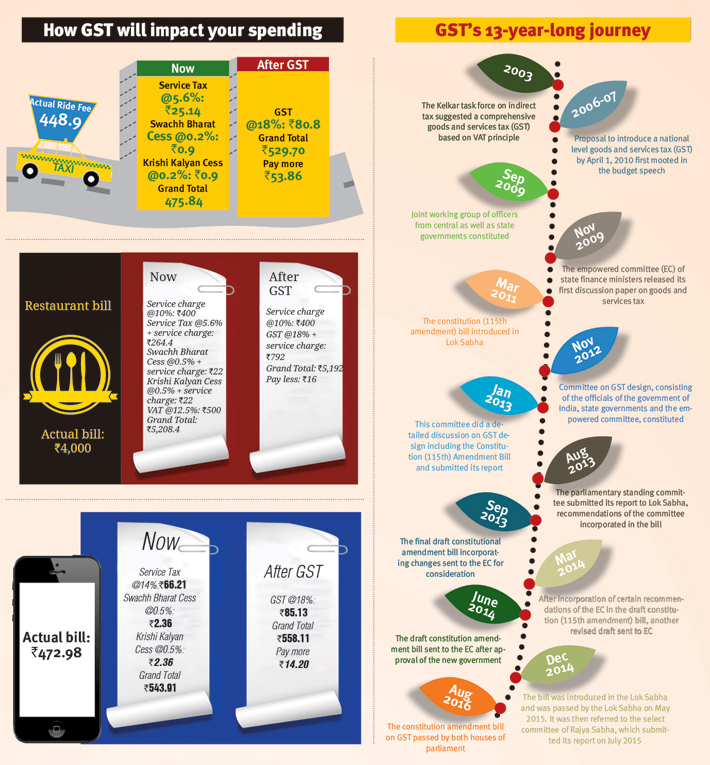

The 122nd Constitutional Amendment (GST) Bill 2014, cleared on August 4 in the Rajya Sabha subsumes all other indirect taxes at the central and state levels to create one single tax – the goods and services tax (GST). The introduction of GST is claimed to be a significant step towards creating a ‘common national market’ and creating a harmonious tax system. This begs the question that why the USA, which is the largest economy in the world, has not implemented the value added tax (VAT)/GST regime, and has a sales tax which varies across states and is decided by states, has not felt the importance and need for a ‘common national market’?

Contrary to the dominant assertions within economics and public policy, universal ‘efficiency’ considerations did not inform the design and implementation of the VAT/GST regime in various parts of the world. Out of the 160 or so countries which have adopted or are in the process of complying with a VAT/GST regime, the reasons for adoption have been varied. In Europe, the question of a common market was important as it was an amalgam of markets separated by boundaries of the nation-states but with a relatively homogenous consumption structure. Even within that, the transition economies of Europe, where the consumption base was much more heterogeneous compared to other countries of Europe, the VAT/GST regime came as a conditionality to join the EU. In Latin America, the introduction of the VAT/GST regime was a part of integration into the global economy, and not creation of homogenous markets within countries. It is only in the ‘developing’ economies of Asia and Africa that the economic rationale for the VAT/GST regime has been based on the ‘efficiency’ argument.

It is indeed a matter of grave concern that there seems to be a collective blinker on the experience of VAT implementation in India which was the first of two steps in the shift towards a GST regime. The argument had been that India’s indirect tax regime is complex, distorted, and has cascading effects due to which there was no significance in buoyancy of tax collection. VAT was supposed to be the efficient tax, based on input credits, which would help to make its administration effective and would lead to increase in tax buoyancy which would translate into a higher indirect tax GDP ratio. More than a decade after its implementation, there is not a single study in India which has found till date a significant, unambiguous and clear structural break in tax buoyancy after the introduction of VAT. In Bihar, on the contrary, we found that except for three tax circles which showed a marginal increase in tax buoyancy, all tax circles showed a decline in tax buoyancy in the five-year period after introduction of VAT.

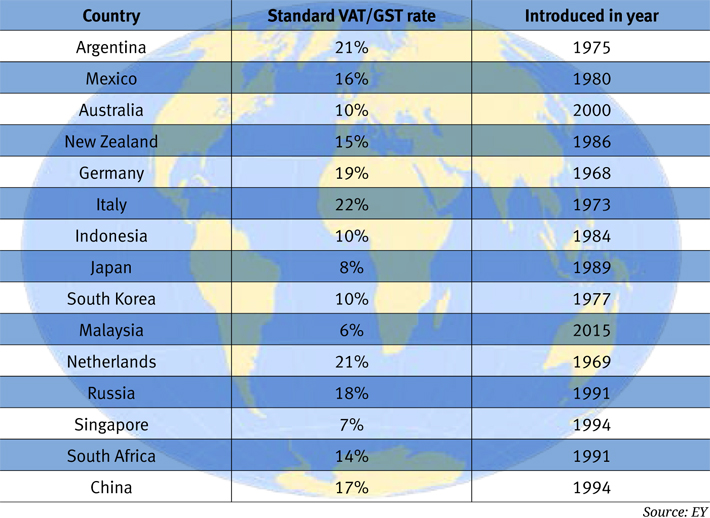

GST /VAT rate in other countries

It has been agreed that the states will be compensated for the loss of revenue on the basis of calculation of a revenue neutral rate (RNR) of GST for all states. These studies are based on datasets in which the tax base is imputed and hence rely on assumptions. There has hardly been any effort by those who are providing technical expertise on GST to study the actual commodity base of the VAT regimes implemented in various states. It is not hard to do. Tax officials of the state governments have this data on their fingertips after the computerisation of tax data.

Our study of tax circle-wise and commodity-wise tax collection from Bihar between 2007 and 2011 shows that around 45% of the total growth in tax collection after implementation revised rates of VAT in 2005-06 is accounted for by petro products, coal and country liquor; and electricity duties. Thus commodities which will be exempt from GST together account for around 50 percent of the VAT base in Bihar. In other words, half of Bihar’s commodity consumption base will be outside the ambit of GST.

The various studies which have calculated the RNR for states using imputations and have informed the debate on GST through these calculations have taken a maximum of 30-35% as the average share of commodities which will be exempted from GST. Thus, the actual tax base assumed in all calculations of RNR for states (even those that have assumed a higher share of exempted goods in calculation of the tax base), are under-projections; and fail to take on board the structure of the narrow commodity tax base of low-income states.

This is precisely where the GST rationale is flawed. It has sold a false binary between production and consumption to low-income states. A middle/high-income state is likely to be a middle-high production state and a high consumption state depending on the composition of economic sectors. A low-income state will both be a low production and low consumption state with a relatively large agrarian base. The only way to ascertain this is to study existing commodity-wise indirect tax regimes in every state. Without doing that, the shift to a GST regime is simply a leap of faith.

Moreover, the GST debate has abstracted away from the issues of intra-state disparity in its assumption of a uniform tax spread within the state in the projection of its potential gains. Thus, it completely ignores the structural constraints of low-income states like Bihar with limited diversification of the economy where Patna accounts for 86% of the total VAT collected in the state. Such issues of spread are not just confined to low-income states like Bihar. A large share of indirect taxes in states like Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra is accounted for by Hyderabad and Mumbai.

Together, the commodity, sectoral and regional spread demonstrates that the existing debate on GST (where concerns of equity has been confined to polemics around whether food should be taxed) and the flawed assumptions on which VAT had been implemented earlier, has failed to take into account the structural limits of the narrow and uneven social consumption base of a primarily agrarian low-income economy with a high degree of informality of transactions.

Should not every state have the freedom to set its tax regime within the specificities of its production and consumption bases in terms of commodities?

Moreover, the question of how and at which point services will be valued in an economy with high level of informality has not been addressed at all in the prevalent discourse on GST. All that GST means today in India is a dual-rated VAT on goods charged at the destination.

It is also a travesty that the hype round GST has successfully deflected attention from India’s highly regressive tax structure in which effective rates of direct taxation have hit an all-time low since 1947.

Das Gupta is associate professor, Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

(The article appears in the August 16-31, 2016 issue of Governance Now)