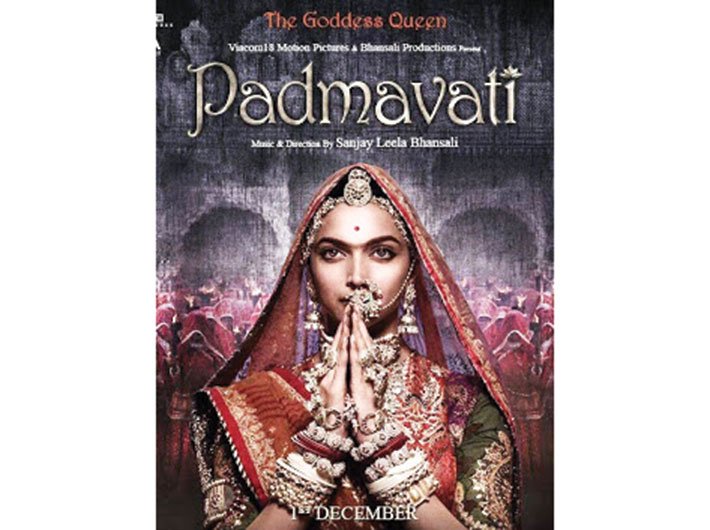

For all the brouhaha and threats of violence by Rajput groups, Padmavati is more fiction than history

There is today a huge uproar about a film produced by Mumbai film-maker Sanjay Leela Bhansali that is rumored to contain scenes of a dream romance between Padmavati, the Rajput queen of Chittor, and the ferocious Muslim sultan Allauddin Khilji of Delhi. Paradoxically, there are a number of conflicting versions of the mythical story of Padmavati over the past 700 years. Now, an obscure Jaipur-based organisation set up in 2006, and called the Shri Rajput Karni Sena (SRKS), has started protests against the film Padmavati, based on Sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s epic poem called Padmavat about a mythical Rani Padmavati. The Sena claims the film is distorting Rajput history and hurting Rajput sentiments.

Allauddin Khilji’s sacking of the great Rajput fort of Chittor in 1303 CE is a historical fact that was enlarged over seven centuries into a legend for Rajput chivalry and sacrifice. The myth, however, has its origin in the poem by Jayasi, written in Awadhi at Ayodhya, in 1540, or 237 years after the sacking of Chittor. Jayasi’s poem has it that Allauddin Khilji went to Chittor to capture the beautiful Rani Padmini but the fort was heavily defended and Raja Ratan Singh tried to escape the fury of the sultan by agreeing to show him his wife, although this act was considered highly shameful. Jayasi’s story says that Padmini only allowed Allauddin Khilji to see her reflection in a mirror from a distance, but the sultan decided that he must capture her and got Raja Ratan Singh arrested and demanded that he surrender his queen.

The myth states that the Rajputs however decided to trick the sultan and sent word that Padmini would be surrendered to him the following morning. One hundred and fifty palanquins forming a retinue of royal ladies went to Allauddin Khilji’s camp. They first stopped before the tent where Raja Ratan Singh was held prisoner. Instead of women, the palanquins actually contained 750 armed soldiers who freed the raja and galloped towards Chittor on horses snatched from Allauddin’s stables. After a long siege, Raja Ratan Singh gave orders that the Rajputs should open the gates and fight to the death while “Padmini” and the women of Chittor committed jauhar, or sacred suicide, in a blazing fire pit, rather than face the disgrace of capture.

The earliest literary source to mention the Chittor siege is the Khaza’in ul-Futuh, by the famed Amir Khusrau (1253-1325), who accompanied Allauddin Khilji during the campaign. He, however, makes no mention of any Padmavati or Padmini. Amir Khusrau also describes the siege of Chittor in a later work, the Diwal Rani Khizr Khanthat, that describes the love story of Allauddin and a princess of Gujarat, but makes no mention of Padmini.

The legend even gets tangled in an old Islamic myth. Some scholars have suggested that Amir Khusrau makes a veiled reference to Padmini in the Khaza’in ul-Futuh by a reference to King Solomon and Bilkis (the Queen of Sheba). According to Islamic mythology, Solomon once set out on an expedition with a vast retinue, which included a bird called hudhud. This bird evidently told him that it had visited the territory of Sheba and described the beautiful queen Bilkis or Sheba. Solomon then sent a message to the queen, asking her to submit before him.

Fifty years after Jayasi, another poet called Hemratan wrote the Gora Badal Padmini Chaupai in 1589, which spoke of a Ratan Sen (sic), the Rajput king of Chitrakot, who had a wife named Prabhavati, a great cook. One day, the king was unhappy with the food she had prepared. Prabhavati challenged him to find a woman better than her. Ratan Sen allegedly set out with a Nath Yogi ascetic who told him that there were many such ‘padmini’ women (a type of women as set out in ancient sex manuals such as Anaga Ranga and Koka Shastra) on an island called Singhal (Srilanka?). Ratan Sen then crossed the sea and defeated the king of Singhal in a game of chess and married his sister Padmavati. The legend says that in dowry, he received half of the kingdom, 4,000 horses and 2,000 elephants. Later in Chitrakot, according to this legend, while Ratan Sen and Padmini were making love, a Brahmin named Raghav Vyas accidentally interrupted them. Fearing Ratan Sen’s anger, he escaped to Delhi and told Allauddin Khilji about the beautiful women of Singhal. Allauddin Khilji set out on an expedition to the island, but his soldiers drowned at sea. He then learnt that the only such ‘Padmini’ woman on the mainland was Padmavati of Chittor, Ratan Sen’s wife.

So he raised an impossibly large army of 2.7 million soldiers and besieged Chittor.

In a variation of this legend, the ocean god punished Ratan Sen for having excessive pride in winning over the world’s most beautiful woman, and everyone except Ratan Sen and Padmavati was killed in a storm. Padmavati was marooned on the island of the daughter of the ocean god. Ratan Sen was also saved. To test Ratan Sen’s love for Padmavati, the ocean god’s daughter disguised herself as Padmavati and appeared before Ratan Sen. But the king was not fooled, so the ocean god then reunited Ratan Sen with Padmavati.

There’s are more such allusions to Chittor and its queen. Five hundred and forty years after the siege of Chittor, the English colonel James Tod briefly mentions Chittor among the many ballads and legends of Rajasthan but makes no mention of Padmavati/Padmini, though he alludes to a Padma of Ajmer. And 270 years later, the Bengali poet Abanindranath Tagore wrote Raj Kahini in 1909, which begins with a brief description of Rajput history and claims that one Bhimsinha marries Padmini after a voyage to Singhala, and brings her to Chittor. Then, when Allauddin Khilji learns about Padmini’s beauty from a singing girl, he invades Chittor to capture her. Bhimsinha offers to surrender his wife to Allauddin Khilji to protect Chittor, but his fellow Rajputs refuse to surrender. Allauddin Khilji then captures Bhimsinha and demands Padmini, but with support from the Rajput warriors, she rescues her husband using the palanquin trick. With such a complex miasma of contradictory poetic legends, it seems clear that there could never have been any historic Padmini or Padmavati. But that the colorful legends of chaste Rajput women preferring jauhar to surrender and the Rajput warriors preferring death to dishonor helped strengthen a Rajput identity of valour and honour.

The Karni Sena had first opposed the film Jodha Akbar in 2008, objecting to the fairly innocuous question about whether Jodha was really the name of Akbar’s queen. But the recent escalation of Hindu sentiments under the Hindutva of the BJP, especially with state elections looming, have encouraged them to greater activity. They were enraged that Bhansali should dare to make a film to show a Hindu Padmavati/Padmini in a romantic dream sequence with the Muslim invader. This sequence was merely rumored and the very few people who have actually seen the film stoutly say there is not a single frame that shows Padmavati/Padmini or the sultan in any romantic situation. These facts did not, however, stop the activists from vandalising the sets of the film. According to a sting operation by an Indian news channel, they may have even created the controversy to extort money from the filmmakers. Several states like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, UP, Punjab and Gujarat, pandering to the hysteria, have banned the film and the producer has postponed the launch – presumably till after the election results. If the film is as beautiful as some believe, the controversy will make the film a huge success and greatly embarrass the critics.

Baig is the author of Ocean of Cobras, a portrait of Dara Shikoh, the liberal-minded, scholarly son of Shahjehan who lost the battle of succession to his staunchly religious younger brother Aurangzeb.

(The column appears in the December 15, 2017 issue)