Swapna Liddle’s book on the grandeur of Shahjahanabad – Old Delhi for the uninitiated – is a billet doux and a splendiferous slide-show

In 1998, as a 12-year-old, I was fascinated by the spectacle on display in the streets of Chandni Chowk, where I grew up, during the Chaudhvin Ka Chand festival, which recreated the Mughal heritage and historical grandeur of Shahjahanabad. The ageing havelis were decked up with bright lights. In some balconies, women danced to the strains of sitar and the beats of tabla. On small stages in the middle of the streets, all the way from Red Fort to Fatehpuri Masjid, poetic Urdu was flowering at mushaiaras and soaring in esctatic crescendos in qawwalis. On one platform, men in bright clothes were playing chaupar, an ancient Indian version of Ludo. At one end of the main street of Chandni Chowk was a massive food court offering old Delhi cuisine. My senses soaked it all in. That was my first immersion in the lost glory of the walled city of Delhi; the latest is Swapna Liddle’s Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi.

Liddle has a PhD on the intellectual and cultural life of the 19th century Delhi. Her first book, Delhi: 14 Historic Walks, is a guide to go with those who would like to foot it past some familiar landmarks and not-so-familiar sites, absorbing history as it probably should be taught. Her second book traces the history of the city the fifth Mughal emperor founded and named after himself. It was the capital of India when the Mughal empire was nearing its zenith, was later administered by the East India Company and then the British government. Now, it forms the walled city area of Delhi. Some chapters include interesting material from Liddle’s doctoral research.

The book will induce sweet nostalgia in those born and brought up in old Delhi – the walled city area to be precise. I have heard from my parents, uncles and aunts some of the stories and references mentioned in the book. They would crop up at conversations over dinner or in relatives’ reminiscences. I have heard about the scenes of loot and plunder after the revolt of 1857 from my father, who in turn heard it from his grandmother, who called it “gaddar”. It was an education. Elders handed out hansels of information that set us off on imaginative or educational quests. Learning that Razia Sultan, Delhi’s 13th century woman ruler, lay buried near Turkman Gate, I would wonder if the spirit of a woman of such importance wouldn’t feel suffocated in the congested streets that have come up around her grave. The book sets off many such trains of thought, in which, for me, history mingles with family stories: my familiar Chandni Chowk linked to Jahanara, Shahjahan’s daughter, who had the bustling market created; the many baghs in the area; the channels of water flowing along the middle of the street; elephant fights; the Bhagirath Palace, once known as Begum Samru’s palace; the Indraprastha Hindu Kanya Shikshalaya, where some of my aunts studied.

For others, the book will summon up the rich history that haunts the streets of the old city. It also mentions little known events such as the Battle of Patparganj (1803), in which the Marathas were defeated by the British East India Company. (Yes, there was a brief spell during which the Marathas ruled Delhi.) Another lesser known incident that took place in Chandni Chowk: in 1739, Nadir Shah of Iran defeated the Mughal forces in Shajahanabad, and acting on a rumour a mob killed as many as 3,000 Iranian soldiers on the streets, Nadir Shah ordered a massacre of men that continued from nine in the morning to two in the afternoon; the women were taken away into slavery. All this while, Nadir Shah is said to have watched from the Roshan-ud-Daula mosque, now known as Sunehri masjid. The mosque – near which the Gurudwara Sis Ganj Sahib has come up – fails to catch the fancy of most passers-by. Knowing that it stood mute witness to an 18th century massacre, evoking thoughts of an earlier massacre by Timurlane, lends it a new poignance.

Liddle’s book also explores how Shahjahanabad exemplified the grandeur of the Mughal empire and its syncretic spirit, being the seedbed from which sprang a rich tradition of music, poetry, culture and Sufism. The people of Shahjahanabad, irrespective of their class and religious belief, held in their hearts a devotion to the Mughals. The liberalism that encouraged such loyalty declined to a great extent after Aurangzeb, the last powerful Mughal, took the throne. His death in 1707 and the effete rulers who took the throne after him saw the British assert dominance. European, chiefly British, ideas of government were brought to India; a new capital was develped; and slowly, Shahjahanabad and its spirit were pushed into the shadows.

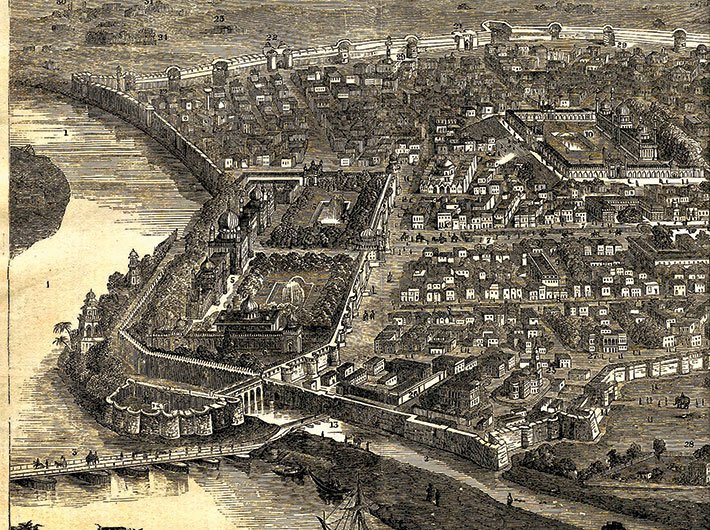

The book, in easy, jargon-free language, also highlights the resilience of the people of Shahjahanabad, who were looted several times, not just by the British. It’s a short book, and includes some sketches that date back to the 1700s. Quite obviously, it’s difficult to chronicle the history of even one part of modern-day Delhi and be brief. So readers will be yearning for more – perhaps about the lives the people of Shahjahanabad lived – from the author.

ridhima@governancenow.com

(The book review appears in May 31, 2017 edition of Governance Now)