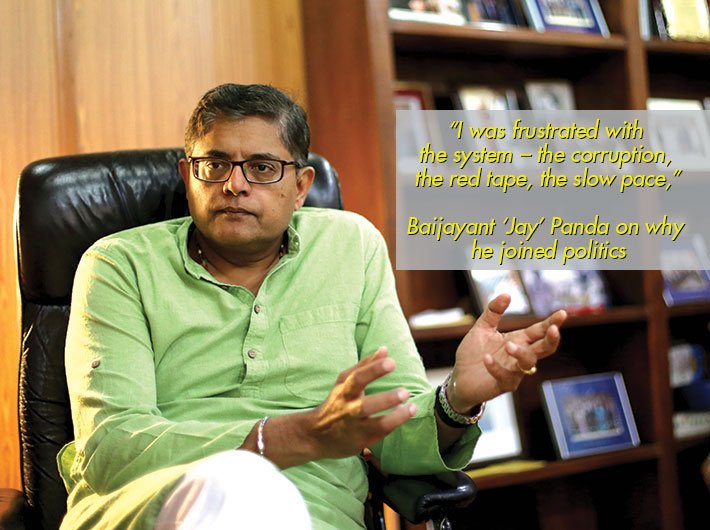

Breaking Bread with Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda, member, Lok Sabha, from Kendrapara, Odisha

Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda feels that coffee would go well with the conversation we are about to have in the elegant, wood-panelled study of his Delhi house. “Do people drink coffee in Odisha?” I ask him to break the ice. “Once upon a time, coffee was not available there. Nowadays, I am amazed to see cafes selling coffee even in remote villages,” says Panda, who represents Kendrapara, a rural district that, he says, had missed development and remained mired in poverty for long. Having been elected to the Lok Sabha a second time, today Panda is decidedly the most recognisable face from Odisha in parliament and one among the group of young MPs involved in public discourses on India’s ground realities.

Jay Panda, as the 53-year-old MP is popularly known, did not set out to be a politician. Having got his engineering and business management degrees from the US, he had joined the corporate world and was moving up the ladder. Then, he and his wife Jagi Mangat Panda launched their own venture – Ortel Communications Limited, a major broadband and digital cable service provider in Odisha that’s also expanding to neighbouring states.

What made him take to politics? The suave MP says it was around the mid-1990s that he felt the mid-career blues. “I was frustrated with the system – the corruption, the red tape, the slow pace,” he says. As he would often crib about it to his friends, some of them advised him that he should rather become part of the system and change it from within or simply “shut up”. “I got involved and was then like a push envelope,” he says.

Opportunity knocked at his door in 1995. He remembers how he ended up hogging the limelight after successfully organising a mega trade fair in Cuttack, his hometown. The then chief minister Biju Patnaik, who happened to know Panda’s family, called for him. “He told me he was impressed with my organisational capabilities and wanted me to assist him.” Soon, Panda started working as the chief minister’s political aide. After the veteran leader died and his foreign-educated son Naveen Patnaik took charge, Jay Panda continued with the new CM in the same position. Three years later, he was elected to the Rajya Sabha as a member of the Janata Dal, which later became the Biju Janata Dal (BJD). In parliament, he stood out from the rest because of his articulation and his meaningful interventions in debates. On the other hand, he was seen engaging with policymakers and the public on key issues related to development.

Parliament, Jay Panda says, made him conscious of India’s realities; his vision had changed. “We are a democratic country and this is wonderful, but we are still a developing nation.” He soon realised that, instead of changing the system, as an MP he needed to work towards creating a level-playing field for all citizens, as the disparities were too glaring. The only way to do it was to allocate more funds for public welfare. “You can’t redistribute (wealth) unless you have surplus – which can come only from economic growth,” Panda says. It was after all unusual for countries to become rich without paying enough attention to development and growth of the economy, he says.

By now we are sipping filter coffee, as the suave MP continues to explain the eternal dilemma of policymakers and lawmakers to maintain a fine balance between welfare and economic growth in a developing setup. Like many economists, he too is following the China growth story with interest. With the benefit of hindsight, he says, one gets an understanding that 30 years ago, India and China were at the same point in their development; both had a comparable level of population and a similar level of poverty. At that point, Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping embraced the market economy, as a result of which, China is the world’s fastest growing economy today. The Chinese economy is five times bigger than India’s. This has also given Beijing enormous diplomatic clout and huge military power while we are just trying to catch up. “Even if we have double digit growth for three decades, we can’t match the Chinese,” he says.

However, the China story would soon face hurdles, he says, as its population (especially its working population) declines, while India would enjoy a demographic advantage. There is something more about India which makes Panda optimistic. He says that, on the bright side, today India is the largest and the most favoured destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the world, which would go into creating infrastructure, boosting industrial growth and eventually creating more jobs. “We are doing well, but we need to speed up things,” he says. He visualises that the advantage of the population surge in coming years would propel India’s economy to new levels. India, with the largest population of young people in the world, has a unique opportunity as no other country. “We should not miss this opportunity and continue to grow for the next 15 years, with creation of more jobs for young Indians.”

However, Panda has a word of caution for policymakers: unless jobs are created, the demographic dividend may soon turn out to be a liability. “In the coming years, India would have to pay much more attention to indicators of economic growth – like the ease of doing business and making development less stressful,” he says. Also, changing positions on policy every year is not good for the country.

Parliament blues

In parliament, Jay Panda came across another disturbing reality: he found that the rules governing the working of Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha are too archaic and not conducive to healthy debate. “I have been campaigning for changing the system in parliament. The rules (of parliamentary business) were framed 26 years before independence; these are anachronistic, borrowed as they are from the 19th century US and UK models of parliamentary systems.”

Panda has been advocating drastic reforms in the rulebook of parliament. Right now, he feels, the agenda of the day in a particular house is decided by so-called consensus, which in reality means the discretion of the presiding authority. “The model worked in the US and the UK, where there were a few political parties and now even they have changed the rules. However, in India, which has 36 political parties in parliament, reaching a consensus on what to debate and the agenda of the House is not feasible,” he says.

The Raj-era system encourages confrontation between the ruling and the opposition blocks, which invariably leads to prolonged disruptions and deadlocks that have become more frequent in recent years. “This is akin to traffic. Let’s visualise Delhi’s traffic scene 80 years ago. There must have been very few vehicles on the roads and, therefore, elaborate rules were not required. But if we keep governing today’s Delhi with the same old traffic rules, one can imagine the chaos it will lead to,” Panda says.

The rulebook of parliament is thick; but actually there should be just one rule – non-discretion. He explains: The agenda of each house is decided by a business advisory committee. Each proposal needs the signatures of three members to be listed in the agenda of the day. Thereafter, everything depends on the discretion of the speaker of the Lok Sabha or the vice-chairman of the Rajya Sabha. There are no clear rules for prioritising the day’s agenda: Even if a large number of MPs are willing to discuss, vote for, or move a motion on particular issue, the discretion of presiding officer will prevail. The only exception to this discretion-based system is the no-confidence motion. The proposal for this requires signatures of 50 members for being listed in the agenda; and for moving it in the house, the support of another 100 members is required.

Panda wants the discretion element to go and, in its place, simple yet clear number-based rules for setting the agenda for parliament. Ideally, the matter should get automatically listed if 50 MPs sign it and it must be introduced for voting if 150 MPs are for voting on it. Also, he says, the rule on moving the no-confidence motion should change; the number of signatures required for listing it should be raised from 50 to 150. This would remove the chances of frivolous attempts to disrupt governments and ensure stability. He says parliament in this large and diverse country is out of tune with the diversity of this country; it needs to acknowledge that taking decisions without voting by elected members is not good.

Panda has also been campaigning against the despotic rule of political parties issuing a whip to their members on voting on crucial motions like no-confidence motion against government and the money bills in parliament. “There are today 330 new members in the current Lok Sabha; lots of talented people of all ages and they can contribute wonderfully to the functioning of parliament. Do they have no opinion? And why should they be always guided by their respective parties in voting on various matters? It should be left to their conscience.” Another basic political reform that Panda has been pursuing is about the funding of elections.

Besides appearing on TV channels and writing an occasional opinion piece in newspapers, how does he connect to the masses on these issues?

“I have been trying to engage with youth through Facebook, television debates and hangouts on these issues and visiting colleges.” What do the young people of India think, I ask him. “I find the younger generation very hopeful about India. They want to be heard and are very keen that the state should create more jobs for them.”

But the fact is that a state entity like Air India has been making huge losses. In this environment, the government can’t create more jobs. “I tell them that there are no instant solutions to the problems facing India. However, the other systems are worse off and it’s from there that we are seeing millions of refugees coming from.” He says the rise of fanaticism across India worries him. “It’s not that this is new; probably, we are getting to hear about it more since it’s being reported.” However, the rising intolerance, he says, is new to India.

Since he interacts with the youth across campuses, how does he look at the occasional eruption of unrest in places like the JNU, I ask him. “We have to keep in mind that the youth of any generation are always passionate, which is fine; if they were apathetic, it would be worse.” He says he himself had “refused to be co-opted by parliament”. “I would always remain a maverick,” he declares.

Our conversation moves back to the economic reforms that lawmakers like Panda would like to play a role in seeing through. He says the recent passage of the goods and services tax (GST) bill in parliament has been the single biggest economic reform in the past 20 years. “Such historic changes should not happen only once in a while if India has to grow.” Without a common law for taxation, the economy was fragmented due to multiple tariffs. It was cheaper for the goods to be shipped to China than to be moved within the country. The GST has helped end this ambiguity, he feels.

Panda says that of late, he has been having a good run in his 12-year parliamentary career. The Modi government banning the use of red beacon – a sign of power and authority for decades – has sent positive signals. He wants all chief ministers to emulate the centre on this and ensure that the ‘lal batti’ is banished from the roads. “My CM Naveen Patnaik has thankfully already done it.” He says the ban may be symbolic, but it has given a huge blow to the promiscuous VVIP culture. “For 12 years, I had been seeing lal battis (red beacons). Why should the minister be different from other people?”

Another reason for Panda to smile on this particular day was the government’s announcement of allocating '3,100 crore for upgrading the electronic voting machines (EVMs) to voter-verifiable paper audit trail (VVPAT) machines. The election commission has already proved that EVMs cannot be compromised but since some political parties were raking up the issue again, this decision has come at an appropriate time and will add to the transparency of our democratic system. “These two decisions have made me feel very good today,” he says.

Our conversation now moves to Odisha, a state, which for a journalist who cut her teeth in the profession in the mid-1980s, was known primarily for acute poverty and hunger deaths. “Decades ago we were desperately poor. Not that poverty has been completely eradicated, but Odisha has made long strides on all fronts,” says the son of the soil. He says today Odisha is the single biggest case of poverty reduction in India. Its infant mortality rate (IMR), maternal mortality rate (MMR) and malnutrition figures have shown drastic improvement.

He says the state had made dramatic turnaround in the last 15 years and its social and economic indices were fast catching up with the national average on many parameters. “Today, malnutrition is a rarity. Massive welfare schemes have played a big role in changing things,” he says. Last year, Odisha clocked seven percent growth, which is pretty decent in the face of the fact that a region like Delhi NCR had registered five percent growth. Way back in 2004, Odisha’s growth rate was one percent; but by 2013-14, its growth was higher than the national average growth.

He says a single scheme – the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojna – was enough to change the face of a state where 94 percent people live in villages and which has 50 percent tribal population. Earlier, during monsoons, the villages used to remain cut off for months. Now with 85 percent of Odisha connected by road, farmers can go anywhere to sell their produce. Agriculture in Odisha is one big turnaround story.

Panda spends at least 12 days each month travelling and meeting people in his constituency. “The place is still backward despite being close to two ports – Paradip and Dharampura. It’s so close to Cuttack and yet not connected through rail. I fail to understand that when stalwarts like Rabi Ray and Biju Patnaik were around, why they never bothered to lay a railway line to Kendrapara. It’s going to take three more years for the railways to come to the district.”

As we take leave, Panda tells me that whenever he travels abroad, he hears positive stories about India. “These essentially come from our economic success story.”

aasha@governancenow.com

(The interview appears in May 16-31. 2017 edition of Governance Now)