You are sitting in your home or office and feel a sudden shaking beneath your feet. The abnormal movement of ground could be a warning sign of an earthquake. As soon as you realise this, a given response to it would be either running out from the building or hiding under a table. In case of a multi-storey building, running down through stairs could turn fatal as you may fall short of time. And, swarming out in large numbers may also trigger the possibility of stampede in an already panic-stricken environment. Such is the nature of a disaster, completely unpredictable.

While natural disasters cannot be averted, the best practical approach is being prepared. What if you are informed 40-50 seconds before the disastrous waves reach you? Would it help you respond more consciously? Would it help the country to mitigate loses by taking precautionary measures within the time frame of a few seconds or minutes? Dr Ashok Kumar, principal investigator of early warning system at IIT Roorkee, believes so. “If you go to small cities, buildings are not earthquake resistant. So if we give them warning 30-40 seconds before a quake strikes, 70 percent of lives can be saved,” he said.

When an earthquake occurs beneath the soil after collision of rocks it generates seismic waves. The primary wave is called P wave. It tosses a building up and down and is non-destructive in nature, experts believe. What brings devastation is the second wave which is called shear wave. It shakes a building back and forth which causes frequencies in earth that travels upwards. So if the structure of a building is not designed to bear this frequency then it may collapse. The time gap between two waves generally ranges from 30 seconds to a minute.

In 2013, the ministry of earth sciences (MoES), in collaboration with IIT Roorkee, started testing an early warning system (EWS) software for earthquakes. The ministry gave a grant of '3.75 crore to the institute to conduct a pilot project. As part of the project, 80 accelerometers have been bought from Taiwan and installed at a length of 100 km in Uttarakhand. Sensors are deployed from Chamoli to Uttarkashi. Roorkee is the central point for receiving data from the network.

The software works on sensors – seismographs and accelerometers. While seismographs are used to find the location and scale of an earthquake, they fall incapable of capturing strong motion earthquake. Accelerometers are capable of capturing the accelerations of strong seismic waves. Data captured from the sensors is then processed in the software to estimate the magnitude of the earthquake and its location. The objective is to get the information from the first wave, and then transmit the alert to the target regions that are at least 50-60 kms away, before they are hit by the second wave.

“The idea is to tell people that an earthquake has occurred after the first wave is generated,” says Dr Vineet Gahalaut, director, national seismology centre, ministry of earth sciences. “But can we transmit this information faster than the speed of destructive waves? That is our objective,” he adds.

The real challenge though is getting reliable information within the first few seconds of an earthquake. “How do you estimate the magnitude reliably? That is where the system (EWS) needs to be trained. It should not generate a false alarm,” says Dr Gahalaut.

Explaining further, he says that the problem lies in earthquakes of bigger magnitude, which are more than six on the Richter scale. Citing an example, he says that Japan has an early warning system. But in 2011, when an earthquake of 9-magnitude struck its Tohoku region the sensors were not able to capture the real number in the first few seconds. “That is where the problem lies. Now you want me to issue information as early as possible. But this information has told us that you have to wait. It was peculiar. It generally doesn’t happen that way.

We normally use 10-15 seconds of data. But that is not always true, especially for big earthquake.”

Therefore, the bottom line is not to have a false alarm. But Dr Kumar assures that chances of false alarm are less likely to happen. “If software is not working on one sensor it will be working on other sensors to capture the earthquake. That is why sensors are very important in every 5-10 kms.”

The early warning system will be put in use for high magnitude earthquakes. “The small earthquake keeps coming and we don’t want to issue warning on each small one. We have set it at six. The source of earthquake has to be in the instrumented area and if the magnitude is six or above then the warning is generated,” explains Dr Ashok Kumar.

The project will be fully implemented in Uttarakhand by March 2016, he confirms.

But it may take some time for national implementation. “We need to check its efficacy and then only it can be put to public use. Also, training and mock exercises will have to be conducted to guide people on how to respond to a disaster,” says Dr Gahalaut.

Unconvinced by the idea of an EWS, Dr Sankar Nath, professor at IIT Kharagpur, says, “For those living in multi-storey buildings lifts will be shut down during an earthquake. So even if you are giving an early warning, how early will you be able to disseminate the information? A minute or half. That’s all. Let us try to be little bit pessimist about it.”

Another challenge as mentioned by the national disaster management authority (NDMA) is communicating the warning. “The major challenge is to have a foolproof communication system to reach out to every citizen in need,” the agency said in a written response.

“We need to have instructions. What is more realistic is to go for disaster mitigation through prevention and preparedness rather than for rescue, relief, and rehabilitation,” suggests Dr Nath. It is also crucial to take a relook at the building structure code. “Going for building code provision and updating it is important. Administrations must enforce that without following seismic-resistant guidelines, nobody can go for urban development,” he adds.

Overhauling the current system

The prime motive of an early warning system is to alert the target regions before high magnitude quake strikes. To receive and process the data in the software, it is essential to have more accelerometers in the seismology network that India presently has, which will further facilitate in replicating the EWS to other parts of the country. Agrees Dr Ashok Kumar: “Strong motion instruments (accelerometer) are very important to capture strong seismic waves. But India has very few of them. The number must be 2,000-3,000 for a big country like ours.”

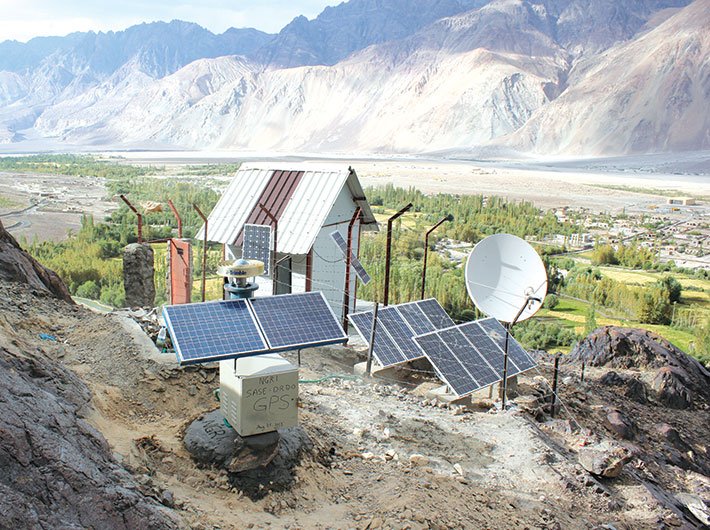

At present, India has seismology observatories at 85 regions that monitor the behaviour of seismic waves and detect its size and location in networked locations. Out of the total, only 40 percent have accelerometers, confirms Dr Gahalaut. However, the ministry is set to expand the network to 122 by next year. “We have bought 78 accelerometers and seismographs to upgrade the network. Now, majority of the observatories will have strong motion sensors,” he says. “As the global seismological networks are expanding rapidly – both in terms of number and in terms of technology –it is important to keep pace with it,” he adds.

Growing urbanisation is also posing another big challenge in tracking the movement of seismic waves. “The cities' limits are expanding because of which the noise level at these observatories has increased. For earthquake monitoring, we need noise-free surrounding. Now if my current observatory is near a railway line or metro line, then it is not a good situation. I need to relocate it,” says Dr Gahalaut, adding that setting up observatories takes a lot of time and efforts.

What is the solution? “There are some suppliers who are coming up with this solution of going underground. There are instruments that can be put 30 meters below the earth. Then probably we can work. These instruments are expensive but we are thinking to go inward,” he states.

Another important thing should be quality of the data collected. “Quality and use of data is important for understanding and researching on earthquake. It will ultimately be used for designing quake-proof structures. Whatever we are designing is not up to the standard. If we have more data it will be efficient to build earthquake resistant buildings,” says Dr DK Paul, earthquake engineer, IIT Roorkee.

Seismic microzonation

MoES, in collaboration with IIT Kharagpur, is working on another project called seismic micozonation. It is aimed at getting more details of seismic-prone regions within the seismic zones. According to its 2002 map, India is divided into four seismic zones – zones 2 to 5. The map is being utilised by earthquake engineers to build earthquake-resistant buildings in the seismic prone zones.

For example, Delhi comes in zone 4. The entire city needs to follow the same structure code as per the map. However, according to microzonation process it depends on the compactness of soil to determine how prone the area is to a quake. So some parts of Delhi may be more prone to quake than others.

Initially, the seismic microzonation project will cover 30 Indian cities. “It will be gradually extended to 42 cities. We want the project to be completed at the earliest with best quality. There's no deadline,” says Dr OP Mishra, scientist and project head of seismic mirozonation, MoES. So far the project has been completed only in Delhi. It is in the final phase in Kolkata. The ministry will soon bring out tenders to invite institutes and agencies with technical expertise to take forward the process across other cities.

Data collected under the project will be used to prepare seismic vulnerability map for the cities. However, despite the process of seismic microzonation being completed in Guwahati and Jabalpur, the information does not seem to have been used by the city development authorities in any manner, says Hari Kumar, president, Geo Hazards Society India.

“Implementation needs to be strong by making it a mandatory code for building construction,” advises Dr Mishra. Also, experts believe that earthquakes don't kill people, collapsing buildings do. When an earthquake occurs, it creates frequency in the soil that travels upwards to the structure. If the structure’s frequency is lower or at par with that of the soil's then there are high chances of building to collapse, explains Dr Mishra.

“Through microzonation, we determine soil parameters or frequencies of that soil property in such a way that the building’s frequency does not match the earthquake shaking frequency. If it does, then there is a problem,” says Dr Mishra.

“We have to find the shaking durability and endurance of the soil property, compactness and the looseness of it. These are important factors to determine in order to design a solid foundation of a structure. So whatever the building will be made that frequency of the building should not match with soil frequency,” he adds.

Building structure code

Most of the cities do not follow the building code for earthquake resistance. Reason? Our building codes are recommendatory and not mandatory. “It will become enforcable by law only when it will become part of building by-laws of cities. Cities are empowered enough to include them into their building by-laws,” says Hari Kumar.

Also there are no special provisions for hilly towns. “The building code which is followed in Delhi is the same which is being followed in Shimla or Aizawl,” he further explains.

Moreover, there are a lot of old buildings existing in many states. So it might be difficult to redesign thousands of decades-old buildings according to the building code for earthquake resistance. “Undertaking mitigation measures in a vast country like ours is a real challenge. Awareness generation and capacity building are the two most important activities for sustainable approach of disaster risk reduction,” says NDMA in its reply to a query.

As a result there should be a lot of emphasis on strengthening the role of key stakeholders in mitigating loses during earthquake-like situation. “In last one decade, various programmes have been conducted by NDMA in different states to develop the capacity of professionals but this has to be taken up at a larger scale. All stakeholders should play a key role, be it state governments, the private sector, engineers, architects, and developers to mitigate the earthquake risk,” the NDMA stated.

taru@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the November 16-30, 2015 issue)