A fair bit of unlearning and relearning is needed before the stakeholders could give the programme a startup DNA that it so desperately needs

It is not very often that government-led programmes actually enthuse the target groups. From that viewpoint, the Startup India event was indeed an applauding success. As chronicled by a multitude of attendees – journalists included – the enthusiasm was contagious.

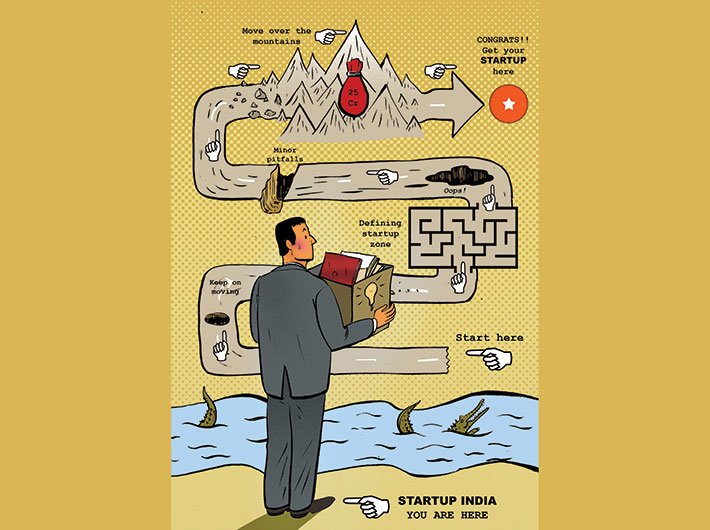

However, as the exuberance settles down, and as the 19-point action plan announced by the prime minister is deciphered, one would soon come to wonder why certain elements were even put there in the first place.

By a stretch of imagination, I get a feeling that the PM himself might have certain reservations on the content of the Startup India blueprint, and I think that it was for this reason he said while addressing the event, “Today's gathering is not to tell us what to do. You have to tell us what the government should not do.”

Seriously, I must seize that statement as an opportunity to list out a few things government should not do if Startup India is to be made a success.

But before I come to that, let me pause and say that launching the programme is certainly a great first step. Moreover, the very fact that prime minister himself addressed the gathering and gave a call to stand up and start up is by itself a very positive message for budding entrepreneurs.

And therein lies a ‘big’ problem

The definition of a startup, as per the Startup India Action Plan document, essentially means that a turnover of '25 crore is big, and crossing that threshold would actually disqualify a company from being a startup.

Consider India’s biggest startup success story in recent years – Flipkart. The company was founded in 2007 and had sales (turnover) of '4 crore as soon as FY 2009. It clocked '20 crore in FY 2010 and '75 crore in FY 2010.

Going by the '25 crore turnover threshold that Startup India establishes, a company like Flipkart would have ceased being called a startup as early as FY 2010, at a time when it was small in reality. Incidentally, Flipkart went on to achieve sales of over '2,800 crore in FY 2014 and is still termed as a startup. Also, it is still two years away from becoming profitable.

So here’s the first thing government should not do: it should not ‘define’ a startup in terms of legacy financial concepts like turnover.

That’s not an incentive

Yes, there’s at least one more finance-related issue that needs to be fixed. Let me elaborate with the Flipkart example. As per its own guidelines, the Singapore-registered and Gurgaon-headquartered company will likely become profitable in 2017 – ten years after it was founded.

Isn’t it a reasonable assumption that in order to sustain and stay competitive against a global heavyweight like Amazon, even a Flipkart likely needs a tax holiday when it becomes profitable? Startup India, however, provisions for only three years of tax holiday in a window of five years. What good is an incentive if a startup can’t ever avail it?

Not that it applies to Flipkart per se, which is anyway registered in Singapore. Still, it is a good example to illustrate the reality faced by startups – so what if they become the size of a unicorn – in today’s hyper-competitive global markets.

The problem is obvious – at least for startups in areas like e-tailing, where turnovers quickly scale into tens and hundreds of crores but often without a break even in sight for years on a go.

So here is the second thing: the government should not link tax holidays to the age of the startup. (There could be a tax holiday for three years after the company become profitable for the incentive to be meaningful)

No monetisation mindset

Yes, the programme stakeholders may argue that the way tax holidays are designed tends to incentivise the entrepreneurs to start earning quick profits. This approach is fundamentally wrong.

Startups thrive best on innovation. The core guiding principle of startups is: create value; money will follow.

Let’s acknowledge it – the birthplace of startups as we know today is the Silicon Valley, and the norm for a startup there is to focus on innovation, not on monetisation, at least during the build-up process. The entrepreneurial norm in India has traditionally been the reverse. (That startups become greedy when they grow into corporations is the subject for another discussion.)

There is a need to build a startup culture as opposed to the profit-making culture that exists in today’s business environment. There should be a focus on IP creation, and solving India’s real problems – not only growth problems faced by the businesses and industries but also the economic, social and environmental issues.

So what is in this context that the government should not do? Let me come back on this a little later.

Incubate, mentor, grow

To its credit, Startup India has got this piece quite right. One set of the 19-point action plan talks about creating incubators for fostering and mentoring startups. The government said it would set up or scale up 31 centres at national institutes.

Even better, the government has done well to recognise the need to mentor potential startups in a pre-incubation stage and then ready them for incubation. The framework is outlined under a proposed Atal Innovation Mission (AIM) with Self-Employment and Talent Utilization (SETU) programme.

However, there is enough room for further improvement. At present, there seems to a developmental skew towards a few sectors and urban centres where these incubators would likely be located. The list of participating departments and agencies for setting up of new incubators is indicative of that skew. The list reads: department of science and technology, department of biotechnology, department of electronics and information technology, ministry of micro, small and medium enterprises, department of higher education, department of industrial policy and promotion and NITI aayog.

Remove the disconnect

The opening statement in the action plan defines Startup India as “a flagship initiative of the Government of India, intended to build a strong ecosystem for nurturing innovation and startups in the country that will drive sustainable economic growth and generate large scale employment opportunities.”

Further, with this action plan the government hopes to “accelerate spreading of the startup movement from digital and technology sector to a wide array of sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, social sector, healthcare, education, etc.; and from existing tier 1 cities to tier 2 and tier 3 cities including semi-urban and rural areas.”

However, the rest of the document, including the detailed description of what qualifies to be a startup, seems to be overly fixated on technology. Of the 31 centres that are proposed to set up or scale up, 18 would be Technology Business Incubators (TBIs). Also, the fact that these TBIs would be set up at premiere institutions like IITs and IIMs, means they would be mostly located in large urban centres.

There is a special section in the document dedicated to biotechnology, which is a good thing. However, it would have been better if a sector like agriculture was given a primary thrust. It would have also been good if there was a focus on sustainability issues like air pollution, water conservation, sanitation, municipal solid waste management, renewable and alternative energy generation, afforestation. There also is a need for skilling a rapidly growing population of youth so that they could become employable by various sectors.

Yes, that would have certainly meant that NGOs could have got a more active role to play in nation building, while also becoming channels for generating employment. However, the action plan in its current form fails to see that opportunity as it is also (apart from technology) fixated on monetisation. How else would one otherwise explain that the definition of a startup doesn’t include entities such as trusts or NGOs and only lists out private limited companies, registered partnership firms and limited liability partnerships?

In its current format, Startup India is about creating just another category of businesses – apart from the existing ones like large enterprises, small and medium enterprises and micro enterprises – with a likely focus on the technology sector.

That’s very much a third thing that the government should not do.

And there’s more

Did I forget to say that the government should not attempt to define a startup in the first place? Well, if I didn’t, then let me state it now: it should not.

While I was concluding this write-up, a journalist friend who has gone through the grind to transform herself into a social entrepreneur, in a social media timeline post described Startup India as “another Rojgar Yojana (employment scheme) with a modern name”. I find that quite apt, and think an even better term would be “swa-rojgar yojana” (self-employment scheme).

It is also being apprehended that, like it has happened with other government schemes in the past, Startup India funds also have the potential to get misappropriated by undeserving fraudsters.

Does that mean that the government should not have taken Startup India step? No.

The government certainly deserves the credit for thinking of startups and taking a step to help build more startups. It has clearly faltered somewhat but then all startups do. The faltering is because the government has thought... well, like a government. To take the right steps, it will need to think like a startup. In fact, the team in the government that is driving this whole programme should think and act like a startup.

That may not be easy, because all these years the government has thought and acted differently! Now, in order to appreciate the startup model, the stakeholders will need to do a bit of unlearning and relearning. Are they ready – and game for it?.

(The article appears in the February 1-15, 2016 issue)