Remote sensing has been used globally for urban and rural development. India is gradually warming up to its potential

The Indian space research organisation (ISRO), which has made the developing country a frontrunner in the space sector, made its first forays in remote sensing way back in the 1970s. India, however, failed to make good use of it, remaining a laggard in spatial technologies, even as images generated by its satellites are used by 14 countries including the US.

After decades of indifference, the ministries and departments are now coming around to appreciate the use of satellite maps in planning, implementation and monitoring. Within a span of two months, the national remote sensing centre (NRSC), working under ISRO, has signed MoUs with the ministry of water resources, river development and Ganga rejuvenation and the ministry of rural development and panchayati raj. While the former is meant for keeping a tab on Ganga pollution, the latter is for effective implementation of the integrated watershed development programme.

The water resources ministry has launched an Android app which can be used to collect and report information on pollution sources. It is a crowd-sourcing platform to monitor pollution in the Ganga and help decision-makers prioritise interventions, ministry officials said. The ministry and NRSC will work together to devise geospatial tools for various aspects of the Clean Ganga initiative. They will also set up a web-based application for river water quality monitoring. The department of land resources under the rural development ministry has sought ISRO’s help in monitoring and evaluation of 50,000 micro watersheds across 10 states and 50 districts.

The NRSC has developed a mobile application to integrate field-level activities and their monitoring with a dedicated portal (bhuvan.nrsc.gov.in).

In the past the ISRO has developed applications for the ministries of environment and forests, agriculture, rural development and earth sciences; and these have paid dividends too. The forest survey, initially conducted every decade, is one such example. The use of remote sensing technology by the forest survey of India has cut down the time taken for survey to two years.

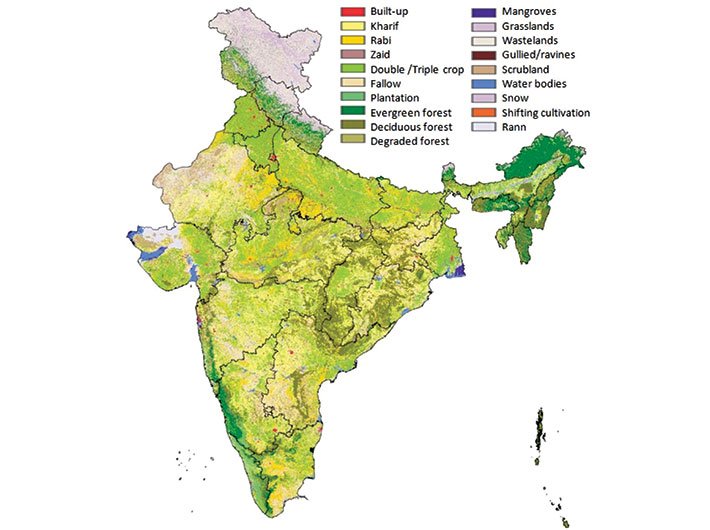

The NRSC has, with the agriculture ministry, developed systems for crop forecast and drought assessment and monitoring. They thus use optical remote sensing (mapping using light) and microwave remote sensing (mapping through transmitting and receiving microwaves) to map 10 crops including rice, wheat, potato and sugarcane, and forecast the yield.

This helps the agriculture ministry in the planning process – from import to procurement to storage. The methodology was developed at NRSC, and was later transferred to the Mahalanobis national crop forecast centre, set up in New Delhi in 2012.

Ocean informatics is another successful remote sensing application. The satellite imagery of ocean helps in identifying the potential fishing zones, eventually benefitting lakhs of fishermen. The technology was developed by ISRO and later transferred to the Indian national centre for ocean information services (INCOIS) based in Hyderabad. Using satellite data, INCOIS measures the speed, wind direction, and wave height. This information is integrated with data obtained from field equipments deployed in the coastal zone. The information thus obtained on the possible fishing zones is shared with states with coastal boundaries. The fishery departments of these states send mobile messages to the fishermen, who then plan their day accordingly. ISRO has also developed a state-of-the-art tsunami advance warning system.

The ISRO’s satellite monitoring of a rural project has been termed as a best practice by the World Bank. Between 2002 and 2009, the Karnataka government implemented Sujala, a watershed cum poverty alleviation programme. The work progress on the ground, performance monitoring and final payment to implementation agencies was done only after satellite scrutiny, which acted as a great deterrence against corruption.

These initiatives are the results of two decades of collaborative work with the line ministries. These are, however, the only applications of remote sensing which have been put to rigorous use by the respective user agencies. The bureaucracy is still not accustomed to geospatial governance. Even as satellite images of cities and villages are made readily available by NRSC, they are rarely used by state planning commissions and city planners. “There is a need for a huge outreach to make policymakers aware of the utility of satellite imagery,” said PG Diwakar, a senior ISRO scientist and deputy director at NSRC, Hyderabad.

In a conference on June 5 in Bengaluru, former ISRO chairman UR Rao recalled meeting a farmer during his US visit in the early 1990s. He said, “The farmer used Indian satellite data to identify the land area with lower productivity. He carried samples of the soil to the nearest laboratory to get advice on the type of crops to plant and fertilisers to use as per the soil properties.”

Though NRSC has set up a centre in each of the 28 states, most of them – except a few like Gujarat and Maharashtra – have been indifferent to geospatial technology, said another ISRO official.

Take Karnataka for example. The state remote sensing centre has developed G-CARE, a web application for integrating state crime records bureau database with the spatial data to help police locate crime and other events to maintain law and order. But the application, developed in 2012-13, is not being used by the police department.

Access to digital maps is also often problematic, as non-governmental research organisations and individuals working for communities have to pay to use them. India’s pricing policy doesn’t allow free access to similar maps. Satellite imagery maps are generated using taxpayers’ money and they should be given back to the community, said Sudarshan Rodriguez, who teaches map usage to people in cities and villages.

He pointed out that the US government provides free access to satellite data of moderate resolution, called Landsat. It provides historical data of four decades and is precious for people working in agriculture, geology, forestry, regional planning, education, mapping, and global change research.

There is a need to create platforms and interface for sharing and updating maps, Rodriguez said. It is unfortunate that government departments share hard copies of maps when sought under the RTI Act, he said. Once it is made publicly available, it might create demand from the bottom for greater use of spatial technologies in governance, he said.

As the department of electronics and IT (DeitY) moves towards launching a national GIS platform under Digital India, one hopes that issues related to application, training and access will get addressed.

pratap@governancenow.com

(The interview appears in the July 16-31, 2015 issue)