The notional credibility of a pre-poll alliance is comparatively higher than the post-poll coalition.

It is that time when contesting parties take the road less travelled, woo their voters with dream schemes and swear by their promises. Each party attempts to gerrymander vote share and appease voters with the sole objective of winning maximum seats in the area. In the fragmented marketplace, it is monastic to envisage a clear winner, who succeeds in winning two-third of the assembly benches. And thus, are born coalitions or alliances.

Coalitions are essentially a permutation born out of arithmetic. They are the modus operandi, in the absence of a clear winner. The first coalition government was led by Morarji Desai in March 1977 which lasted till June 1979. Since then, India has witnessed both natural coalitions (Shiv Sena - BJP) based on similar ideologies and misplaced coalitions (Mufti - BJP) based on no visible common ground.

Coalitions are based on arithmetic convenience and negotiations. Alliances are formed by parties that mutually (or claim to) support each other’s ideology, and see eye to eye before the commencement of elections. Alliances avoid pitching opposing candidates, display a joint show of power and leverage on each other’s vote bank. They may be running together for a common cause or a common enemy.

“In politics, common enemies are identified before common friends,” says Kumar Ketkar, a veteran political analyst.

The notional credibility of a pre-poll alliance is comparatively higher than the post-poll coalition. When two opposing parties collaborate post elections, to pass the test of numbers, voters of either parties may stand disillusioned. They view the coalition as an arrangement that is purely political in nature. This triggers an air of scepticism that lingers during the entire term. Leaders need to keep proving themselves, to ensure the voters do not switch sides. Coalition members are repeatedly making ideological adjustments, to keep the numbers intact.

The 25-year old BJP Shiv Sena alliance was called off before the Maharashtra elections itself in 2014, one of the reasons being incongruous math behind seat sharing. In October 2014, BJP fell short of 145 seats in Maharashtra. After multiple rounds of negotiation, one time natural partners in alliance, Shiv Sena and BJP formed the coalition government in Maharashtra. However, the camaraderie was conspicuous by its absence. More than two years hence, the coalition has weakened. As the two parties decide to part ways for BMC elections 2017, this is the journey of a natural alliance to a claustrophobic coalition.

The BJP-Mufti government in 2016 at Jammu and Kashmir is a glaring chalk and cheese coalition for the nation. Political analysts could not see this beyond rudimentary arithmetic. Latter half of 2016 is testimony to the brittle nature of this odd alliance.

Coalition is a low risk low return strategy. Since the parties do not invest in the relationship before polls, they are not obliged to deliver on each other’s manifesto.

Pre-poll alliances, on the other hand, are aspirational in nature. Since these alliances are forged way before voters hit the road, they are not coalesced solely on the back of power and position. These alliances typically comprise of parties that either want to consolidate vote bank and/or fight against a common threat.

BJP had won 282 seats and 29.86 percent votes in the 16th Lok Sabha elections in May 2014. Fast forward to November 2015, a pre-poll alliance was formed between Janata Dal (United) (JDU), Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), and Indian National Congress (INC), which proved to be a decisive. BJP’s vote share fell to 24.42 percent in just eighteen months. One may argue that citizens vote differently in national and state elections. Even if that proposition were to be true, one wonders if the vote share would shift so dramatically, if this was a post-poll coalition than a pre-poll alliance. Moreover, there has been no alleged squabbling between the Bihar alliance members. The cohesive forces are visible as alliance members share stage to send a resplendent message of unity to voters and opposition alike.

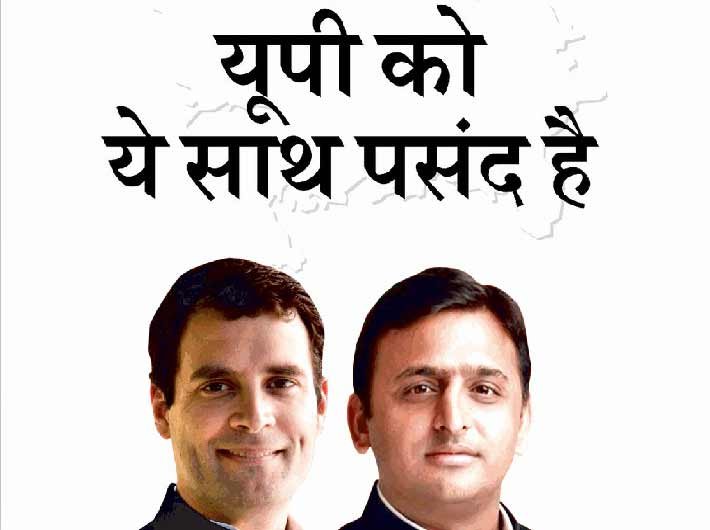

Another high-profile pre-poll alliance that deserves discussion is the INC-SP alliance in Uttar Pradesh. This alliance is a realistic leap for the national party and a risk mitigating strategy for the ruling party in the state. Obviously, both parties run the risk of losing loyal supporters and party workers, who may not approve of the alliance. This risk can be mitigated if the two leaders communicate their underlying intentions unequivocally and convince both camps of the alliance synergy.

INC suffered from chronic anti-incumbency in 2014 across board. SP voters who continue to latch on the sentiment would dismiss the pre-poll alliance, and even contemplate voting otherwise. INC workers who believe in the stand-alone merit of their cadre would perceive this alliance equivalent to the leadership conceding even before the polls.

Political landscape is still decoding the underlying principles of a pre-poll alliance. In its current form, it is not seen as a marriage of ideologies or a struggle for a sordid cause. It is a coalition based on ‘projected numbers’ at best. With increase in number of parties, and raised aspirations of regional parties, devices that burnish performance of alliances would need to evolve. Intuitively, alliances score better than coalitions on three main fronts:

Firstly, alliances reduce the number of contesting points in the election polygon. This reduces the probability of a hung assembly and implicitly increases the size of each slice of the pie. Odd and desperate coalitions are kept at bay, since the numbers are taken into account well in advance.

Secondly, the alliances campaign jointly communicating their best ideas. The manifesto is quintessentially the crème de la crème of each alliance member. Alliances tend to invest higher energy in convincing the voters about their intentions and commitment to the alliance, compared to individual party campaigns.

Thirdly, alliances form the basis of future political relationships. Alliances help parties expand their base in other regions. In April 1999, BJP lost vote of confidence in Lok Sabha, by sheer margin of one vote.

This prompted BJP to scout for pan India partners, which would eventually lead to the formation of National Democratic Alliance (NDA) before the Lok Sabha elections, 1999. Similarly, the proposed Mahagathbandhan may prove a decisive piece in devising politics of tomorrow.

As we inch closer to 2019 elections, and the oldest national party already forming pre-poll alliances in both Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, one cannot help wonder is this of prognostic importance. If these alliances deliver in the next two years, and more such amenable alliances are formed in the next 10 state elections due for 2019 Assembly polls, Modi ji will have to make some new friends and befriend old enemies.

More power to governance!

(Kapoor is an associate fellow at Pahle India Foundation)