Diplomat-poet Abhay K’s new translation of the Sanskrit classic is especially sensitive to rich biodiversity of ancient India

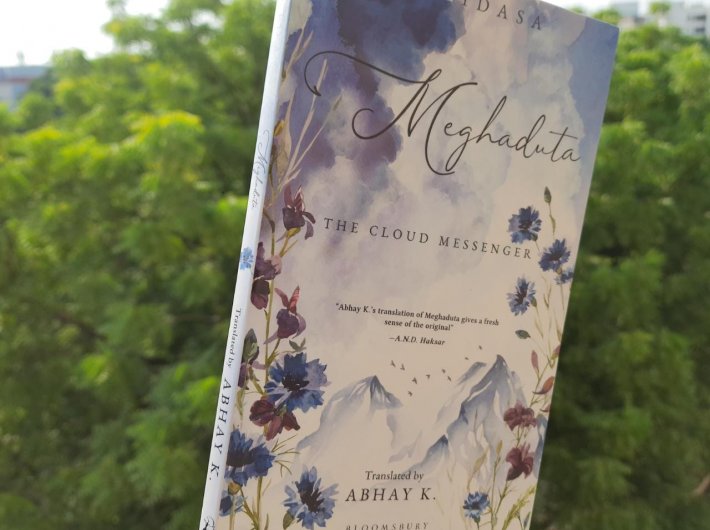

Kalidasa’s Meghaduta: The Cloud Messenger

Translated by Abhay K.

Bloomsbury / 114 pages / Rs 399

‘Meghduta’, a ‘messenger-poem’ of about 110 stanzas, is among the most precious jewels of Sanskrit literature, a classic acknowledged around the world for centuries. It is arguably the one work of Indian literature translated most often: Around 250 editions exist in various languages. In English, it appeared the first time in 1813-14 in the translation of Orientalist Horace Hayman Wilson, and there have been dozens of further renditions. The latest in the series is this one by diplomat-poet Abhay K. Why one more?

“A classic is a book which with each rereading offers as much of a sense of discovery as the first reading,” says Italo Calvino (whose birth anniversary would be celebrated this week). The many aphoristic definitions and characteristics of classics from the Italian master repeat this theme: Classis is the one that has never finished saying what it has to say. And a translation is a way of reading. A new translation, above all, reads the work from a contemporary perspective, apart from expressing its content in contemporary parlance.

Thus, while Abhay brings his poetic sensitivity in rendering in mellifluous English the exiled Yaksha’s plea to the cloud to take his message to his beloved, what is more striking is the awareness of nature in the great poem.

Yes, ‘Meghduta’ is a sensuous love poem. Kalidasa’s incomparable descriptions of natural beauty come from a lover who is separated from his beloved at the beginning of the monsoon season. In giving the roadmap to the cloud and marking out regions along the way, he can’t help but speak of rivers and mountains in sensual ways:

“Like the slender arms of the lady river,

Vanira branches reach out to take away her

Water garment and expose her thighs, the banks.”

It is the coming together of two perennial themes of poetry, romantic love and beauty of nature, that has made ‘Meghaduta’ readers’ favourite over centuries. And Abhay has made it available, accessible to the next-gen readers too. When A.N.D. Haksar, among the most respected names in Sanskrit-English translation, praises this work as “very well translated” and bringing “a fresh sense of the original”, little needs to be said further on that count.

Yet, the added reading that Abhay’s version highlights is Kalidasa’s acute awareness of the rhythms of nature, of the fragility of flora and fauna. In this marvelously produced edition, there is a concerted effort to chart the biodiversity of India of the fourth-fifth century.

In his prefatory note, the translator writes:

“Lockdown across the planet has taught us to pay attention to our surroundings as Kalidasa has done in this exquisite poem, reminding us of all the beauty waiting to be discovered by slowing down, listening to birdsong, smelling the fragrance of flowers, reading books, thinking about our relationship with the nature and how to tackle the three biggest challenges our planet faces today—biodiversity loss, climate change and environmental pollution.”

This edition, thus, presents a compendium of the names of “the plants and animals, rivers, mountains, traditions and styles”. ‘Sarika’ is a common talking Maina, Gracula religiosa, ‘Madhavi’ is a kind of Jasmine and ‘Kurubakas’ is amaranth hedge. These footnotes recreate for us the world of Kalidasa, the world that is vanishing before our eyes.

In Abhay’s translation, the great poet is inviting us to pay attention to our relationship with the environment. Nature is traditionally seen as the nurturing mother (“Mother Nature”), but it could be a beloved too. And the beauty of that beloved will wither away, if we are not careful.

Also read: A previous interview with Abhay K:

https://www.governancenow.com/views/interview/poetry-and-diplomacy-combine-ambiguity-and-brevity-diplomat-abhay-kumar