Interview: Bijal Brahmbhatt, director of Mahila Housing SEWA Trust and co-author of ‘The City-makers’, talks about women, shelter and civil society

Home. One word with so many connotations. For urban poor women, shelter is the answer to a wide range of problems, and the single solution to a better future. For the women working in the informal sector, as maids or street vendors, the living place comes with a host of challenges – from fighting for access to drinking water or depending on unreliable electricity connection to a constant sense of insecurity and anxiety over the threat of eviction. Munish of Savda Gevra Resettlement Colony in Delhi summarises it all succinctly when she says, “If you have a house, then you have everything. Even if someone comes from outside, he can’t do anything because you are in your own home. If you don’t have a house, you have nothing.”

Yet, paradoxically, there have been few initiatives from the civil society sector to respond to this deep need. The Mahila Housing SEWA Trust (MHT) [https://www.mahilahousingtrust.org/] is the pioneer in uniting women for solutions to a variety of issues revolving around the question of shelter.

The Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), established in 1972 as a trade union of poor, self-employed women workers, has over its close to half a century of journey responded to such challenges by replicating its model in a new but related area, keeping faith in the collective voice of behens (sisters). When women started complaining about their habitat, an idea was crystalised and led to the founding of MHT in 1994.

Over a quarter century, the Trust – and its members – faced those challenges, from very local to pan-national, from simple to highly complicated, and went on succeeding. They also expanded their footprint to 36 cities within India, and a couple of cities abroad.

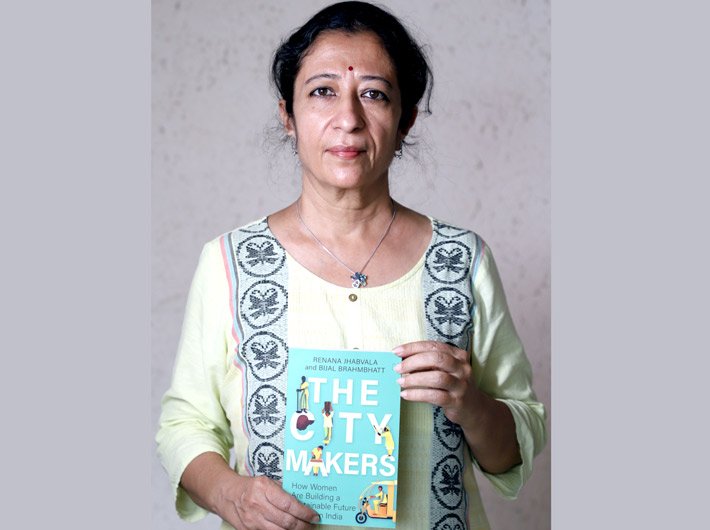

The journey must have entailed cumbersome, often frustrating, processes, and writing a story of its 25-year saga must have been equally challenging. It is too the credit of Renana Jhabvala, chairperson of SEWA Bharat, and Bijal Brahmbhatt, director since 2009 of MHT – the guiding forces behind the movement – that they have produced a lively, highly readable account in ‘The City-Makers: How Women Are Building a Sustainable Future for Urban India’, published by Hachette recently. The report they present has its minutiae of ground work and policy details but it also captures the spirit of women like Meena, Mumtaz and Parul, who are among the 1.7 million individuals whose lives the MHT has changed for better.

Read an excerpt from the book:

Advocating for Cities Where the Poor and Women Count

In an email conversation, Bijal Brahmbhatt answers a few questions – and shares a story.

At first glance, ‘The City-Makers’ appears to be a quiet and gentle work, but on reading, it turns out to be a lively and vibrant book! You have mentioned how the idea of an organization like MHT came up. Over the 25 years, how has its mandate evolved?

MHT was established about 25 years ago, initially with the mission to improve the housing, living and environmental conditions of the poor women in the informal sector. At that time, we had no blueprint to work upon. The work was majorly demand based. We used to go out to the slums, hold meetings and gauge the demand of the women. The demand mainly then, was around access to water and sanitation. It still remains the same in underdeveloped states of India like Jharkhand. Our work was intertwined with empowerment of women around these issues and then evolving as the demand also evolved. The habitat development initially began with the water and sanitation, progressed from there to energy, housing and housing finance, and then started moving on to related climate change and governance issues. Again, Community Action Groups (CAGs) empowered by MHT, who started working with their own households, moved on to work at slum level and then city level. Thus MHT’s mandate now is to create empowered Community Action Groups of Women who work towards sustainable and responsible urbanisation.

Land and property are usually the prerogative of the male elder of the household, though the policy intervention has led to slight correction. The MHT in its very name has focus on women. How has the gender question in property matter shaped its journey?

In most states, by policy, now the property/land is in joint name, with the women’s name first. MHT has for years struggled to bring in this policy change. Our experience on ground, though, has been that when we are working on issues like water sanitation and access to energy, it is easier to work with women, and build their leadership, uninterrupted by the menfolk of the community. But when it comes to huge asset building, like affordable housing itself, men offer huge resistance to women’s participation and decision making. The bureaucracy and the private sector are actually indifferent. In slums, where the legal title is not possible easily, MHT tries to build the assets slowly in the name of the women, for example, getting the water bills and the electricity bills in the name of women, issuing a housing loan with the women’s name first, etc.

The government as well as the commercial real-estate sector too had toyed with the idea of low-cost housing about a decade ago, but it has not made much impact. What do you think was missing?

In our experience, out of 10 housing constructed in India, seven are built incrementally, by the people themselves, two are built by the private sector and one by the public sector. Our experience in the slum networking project (SNP) programme with the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation has shown that given basic effective infrastructure (water, toilet, sewerage, storm water drainage, solid waste management, etc.) together, that is, facilitating slum upgradation, 99% of the people upgrade the housing themselves. Unfortunately that approach has been stopped by the government. The privates sector is constrained due to land prices and the kind of development control regulations put in by the government, which in our experience increases the costing of a housing unit anywhere between 23% and 33%. The government should encourage approaches where self-built housing, incremental housing by the people themselves is promoted. Also, despite several efforts, housing finance is still not available for the informal income, informal tenure, which affects the investments of the poor themselves into housing.

That also brings us to the current government’s initiative of ‘housing for all by 2022’ under the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana. How does the MHT evaluate its implementation and progress?

There is no doubt that the yojana has brought focus on the issue as never before. However, it is also very true that the progress has been very slow. The progress has been comparatively better in the states like Gujarat, where, due to a better urban planning regime, ample land reservation for the poor is available. Again, where a specifically beneficiary-led construction scheme is concerned, since the government policy specifically requires legal land title, implementation has been very slow and not taken off at all in metro cities. The approach needs to be contextualised state-wise for better progress rather than assume ‘one size fits all’.

The MHT has helped in building resilience to climate change among the urban poor communities. There are four inspiring stories in the book showing how urban poor women became change agents. While they are among the most affected communities, how do they in general balance economic imperatives and environmental concerns?

It is true that balancing economic priorities and environmental concern is a real challenge, especially for poor women who are more worried about short-term and pressing priorities like where to get the next meal from or paying the fees of the children. This is again more true as MHT is working on slow onset but potent disasters like heat stress. However, on one issue, the women were very clear. They did not want their children to live the kinds of life that they had led. When they understood that the lives may be worse due to climate change, they immediately decided that working on those issues would also be one of their priorities. Again some of the negative impacts of climate change, like water scarcity, is something that they face daily, as a struggle to survive. Then they immediately get organised around such issues.

Would it be fair to say that a majority of the shelter-related challenges faced by the urban poor women could be solved to a large extent with political will, bureaucratic efficiency and legal reforms? What has been the MHT’s experience of dealing with political leadership and officials?

Yes. It is fair to believe so. Working with political leadership and the officials have been a mixed experience. We do have a history and approach of working in partnership with Governments, however, in [some] instances the right-based and activist approach is also needed. The MHT employs the dual strategy of making partnerships for change and also taking an activist mode wherever needed. However, whenever a more activist mode is required, we have trained the Community Action Groups that we have developed to do so. The MHT itself sticks to the partnership model.

The MHT has come a long way, both in terms of its geographical change and the themes. What are the future plans?

The plan going forward is to grow across India and work towards responsible urbanisation, in a way that:

(1) Inclusion of preferences and needs of every last person (the most vulnerable – women, girls, poorest of the poor and disabled), which often gets neglected due to lack of their representation in the decision making, but are the most affected by such decisions.

(2) It is environmentally friendly, i.e., it takes conscious, scientific care regarding the long term effects on air quality, temperatures, inundations, weather, and hence a healthy (mentally, physically and socially) habitat of everyone in the city.

(3) It is sustainable both in terms of usage of the scarce natural resources and ensuring the ability of everyone living in the city to maintain it by themselves (not needing an agency like MHT to do it for them).

This will be undertaken mainly by building and concentrating on development of more Community Action Groups (CAGS) to ensure sustainability, increasing access to housing finance, advocacy for impacting policies. From 2000 to 2016, that is, in 16 years, the MHT directly impacted the lives of 1 million individuals. We now want to increase the pace three times by reaching 1 million people in five years, from 2017 to 2022.

‘The City-Makers’, as already noted, tells numerous stories of gutsy women who are making a change. Would you share one that warmed your heart the most?

[In reply, Brahmbhatt shares the Story of Fahmidaben, read it at the link below]

How Fahmidaben found her voice – and helped her neighbours

With training and guidance from Mahila Housing SEWA Trust, a slum-dweller works at improving her surroundings