The best use of the increased political capital will be in launching a second round of big bang reforms

The elections, acrimonious as ever, are over. The results, predictable as ever in hindsight, are out. Now the elected leaders should get down to delivering what people have asked for. The election campaign was dominated by emotional and ideological factors, with exchange of personal allegations, rather than issues concerning governance and economy. That should end now, making space for a more reasoned environment.

Apart from a slew of welfare initiatives, partly responsible for the BJP’s outstanding performance in elections, the previous government made a few bold decisions concerning economy. The bankruptcy code merited unalloyed praise. GST could have been better calibrated in the initial phase, but showed the NDA government’s resolve to build on the legacy of the previous government in the best interests of the economy. Though not counted among the aims of demonetisation, the step led to a shakeup of the tax administration, and we should expect a thorough clearing of it in the new term.

While appreciating the Modi government’s boldness to go for unpopular measures, experts would say that this virtue would be best put to use in a number of areas where reforms have been pending for long because no government has shown necessary guts. Labour reform is the obvious example.

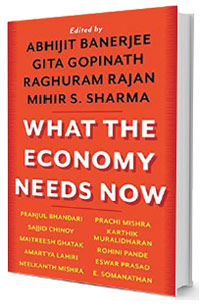

“A key factor in spurring growth will be reforms that alleviate ‘supply side’ constraints on growth and job creation. We have to enable both the industrial sector and the service sector to operate at larger scale. This involves embracing highly overdue labour reforms including allowing for a rich menu of contacts with workers that allows for more possibilities than just permanent workers and short-term contractual labour in firms,” write the editors of an excellent and brief work, ‘What the Economy Needs Now’ (Juggernaut).

Edited by Abhijit Banerjee, Gita Gopinath, Raghuram Rajan and Mihir S Sharma, all respected economists and commentators, the book presents a well delineated road map for policymakers at this crucial juncture. Each of the individual chapters on infrastructure, energy, banking, welfare, land, agriculture, education, healthcare, gender and environment is bracketed by a comprehensive introductory note and an afterword. In recent years, divisiveness has conquered economics too and the commentators in this work would be perceived to be for or against this or that regime. But a careful reading shows that the problems identified and solutions offered are above political fault lines. For example, how can one see the call for more cash transfers through the prism of the BJP/Congress, when the governments headed by both have furthered the cause? Direct benefit transfer (DBT) was proposed in 2012 (finance minister P Chidambaram called it a game-changer). Though highly debatable back then, the DBT was only expanded and implemented with more zeal after the regime change in 2014.

Consider this sample of the key takeaways of this book. Among other things, the central message is that “rethinking the government is the key”. India has made enviable progress with an average GDP growth of about 7 percent over the past 25 years. Yet, it remains among the poorest nations, with a lot to catch up especially in healthcare, education and gender equality. The path is challenging because, unlike the growth stories of other nations, India will be treading it when the world is trying to mitigate climate change.

Decentralisation – delegation of more powers to municipalities and panchayats – is a repeated refrain here. Job creation, needless to say, is the top priority for the new government. Small and medium enterprises are badly in need of more hand-holding. Private investments need to rise. There is a lot of work to do in health and education, starting with more budgetary support.

In short, a second round of big reforms, matching in scale to those from the early 1990s, has been overdue for long.

What the book wisely refrains from commenting on are a couple of areas of concern from 2014-19: accuracy of data – be it of GDP or of jobs – has come under increasing scrutiny, we need more reliable data generation. Also, the previous government early on had two globally reputed economists on board, but it could have profited more from their expertise. The new government can do worse than get the right talent in key positions. Thirdly, while secrecy is vital for a decision like demonetisation, predictability (and people’s participation) is vital for economic policymaking in general.

ashishm@governancenow.com

(This article appears in the June 15, 2019 edition)