Can you imagine a day without cash? The answer is an obvious ‘no’. The rustle of notes and jingle of coins still have the power to light up any face. In fact, more than 99 percent of transactions by volume are still in cash payments in India, according to a McKinsey Global Insights report. Some argue that this overdependence on physical money is due to challenges like inaccessible banking services, lack of infrastructure to support non-cash payment and internet connectivity, which continue to persist, especially in the rural and remote regions of India. Others say that Indians are simply cash-obsessed.

But this obsession is costing a fortune to the economy. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and commercial banks annually spend Rs 21,000 crore ($3.5 billion) to print and circulate currency notes and coins, and to keep them safe. Citizens of Delhi alone spend Rs 9.1 crore – and 60 lakh hours – to withdraw and manage cash, according to a 2015 report by the Institute for Business in the Global Context.

Read Interview: "UPI can be critical component for cashless initiatives"

“If you follow the traditional process of creating brick-and-mortar [bank] branches, giving credit, deputing officials, that’s a very tardy process and the cost of transaction will be very high. Digital transactions can help in radically reducing the cost of transactions,” suggested Amitabh Kant, CEO, NITI Aayog, at the Digital Payments conference organised by Observer Research Foundation (ORF) in early October.

Cash, however, is slowly but surely going out of fashion thanks to technology. It started with credit and debit cards (plastic money), and with the rise of information and communication technologies, soon there were many more options to replace notes and coins: internet banking, mobile banking and digital wallets.

Mobile-based transactions are growing rapidly, driven by digital wallets and mobile banking, riding on an upsurge in the number of smartphone users. India has surpassed the US to become the world’s second largest smartphone market in terms of active smartphone users, crossing 220 million users, according to a report by Counterpoint Technology Market Research. This has encouraged non-banking payment solution companies such as Paytm, FreeCharge and Oxigen to flourish and challenge the banking sector to increase its coverage as well as services among non-connected citizens. [Paytm’s market valuation is close to $3 billion. It aspires to be India’s first $100 billion company.]

The volume of transactions via mobile banking has doubled, going up from 171.92 million in 2014-15 to 390 million in 2015-16, as per an RBI estimate. Transactions of m-wallet – a mobile phone app that allows cashless transactions – too have witnessed a jump in volume, touching 604 million compared to 255 million in 2014-15.

Such large-scale adoption of digital finance by emerging economies would boost their GDP by six percent, according to the McKinsey study. “India could see a boost of $700 billion, an 11.8 percent increase by 2025. This additional GDP could create up to 21 million jobs in India,” the report states. It could make new loans worth $689 billion available to individuals and small businesses.

The NDA government’s flagship financial inclusion scheme, Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), gives a push to the transition towards a cashless economy. The scheme offers a RuPay card to the account holder, in order to promote electronic payments. Under PMJDY, 24.27 crore bank accounts have been opened in urban and rural areas so far. Moreover, 19.06 crore RuPay cards have been issued. There is, however, no way to ascertain the number of accounts and cards being actively used.

For instance, take Mohammad Umar’s case. The 30-year-old has been working as a helper at a wholesale shop in Chandni Chowk for the past five years. He earns Rs 8,000 per month. In 2014, he opened an account with Canara Bank under PMJDY. “I now deposit a part of my salary into my account. This way I’m able to save some money at the end of the month,” he says. But he has not yet seen the benefit of electronic payment, even though the bank has issued him a debit card. “I don’t know how to use it,” he says.

“Opening bank accounts under PMJDY is the beginning. Under this scheme, every account holder will be given a RuPay card. ATMs, micro ATMs and point-of-sale (POS) devices, however, need to be compliant with these RuPay cards for effective implementation,” says AP Hota, managing director and CEO, National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), an organisation set up with the help of RBI and the Indian Banks Association (see interview).

The government’s direct benefit transfer (DBT) scheme has also benefitted from PMJDY as the network of bank accounts has widened, allowing better implementation in transfer of subsidies. “While it started from 24 in 2013, today we have 74 schemes where DBT is being implemented. As of now we have made Rs 1,40,000 crore of DBT transfers in the country, covering about 30 crore beneficiaries,” said Peeyush Kumar, joint secretary, DBT, cabinet secretariat, at the ORF event.

Besides, digital finance can increase transparency in the economy and make transactions traceable. It has been one of the priorities of prime minister Narendra Modi. “We need to make India modern, transparent and have to implement procedures across the country. There was a time when transactions happened through barter system. Then notes and coins came. But now the world is moving towards a cashless economy,” Modi said, during his radio address ‘Mann Ki Baat’ on May 22.

“The start will be difficult but once you get used to it, it will be simple … Jan-Dhan, Aadhaar and mobile [JAM] together can help us move towards a cashless economy. If we use the measures [made available by the government] we will be able to bring transparency and reduce black money,” he said.

Countering black money has been one of Modi’s most talked about election promises, and digital payments, with their full transparency, can help reduce the menace. With electronic payments, the government aims to regulate the flow of cash, which mostly goes unrecorded.

“Electronic payments ensure that payments have a history. Apart from that, electronic payment system cuts down the cost of managing cash and risk of carrying cash. Also, cash has the risk related to counterfeiting of money,” Saurabh Garg, joint secretary (investments), department of economic affairs, ministry of finance, said at the conference.

The finance ministry, on its part, has been holding talks with various stakeholders, including the RBI, to discuss steps to promote cashless economy. In fact, a special investigation team set up by the supreme court has reportedly recommended banning cash transactions over Rs 3 lakh.

The central bank this year floated a paper, ‘Vision 2018’, proposing a payment and settlement system in India to “encourage greater use of electronic payments by all sections of society so as to achieve a ‘less-cash’ society”. To achieve this vision, the RBI will work on five Cs – coverage, convenience, confidence, convergence and cost. The central bank aims to increase the coverage of digital payments like net banking and digital wallets, and improving the links between them, while also ensuring there are no frauds in the process.

With an increase in usage of the digital wallet facility offered by non-banking firms, the RBI’s next strategic move is to formulate a policy to build a supervisory mechanism for them. For this the apex bank notes in its paper that there is a need for an “appropriate oversight framework” for new systems, and “augmenting the data reporting and fraud monitoring systems.” The final measure is to build a customer grievance redressal mechanism, which will focus on “building customer awareness and education, and initiate customer protection measures.”

In an another move to push for ‘less-cash’ economy, the NPCI is setting up Bharat Bill Payment System (BBPS), to allow people to pay their utility bills at a single platform through various payment modes including cash and electronic. The RBI has given in-principle approval to Oxigen Services India, BillDesk, TechProcess Payment Services, Paytm and all common services centres (CSCs) to offer services under BBPS.

Let’s take a look at what is driving India’s cashless economy.

Credit/debit cards

In the 1990s, the credit/debit card – popularly known as plastic money – was the only option to actual cash, in times of emergency, for example. Before the advent of mobile/internet banking and digital wallets, cards were the only option to make payments for, say, railway tickets over IRCTC. Also, it taught both parties to trust the transaction without physical money changing hands.

Remembering the first time he used a debit card, Harish Rao, 57, a government employee, says, “It was in 1996 when I got my first Syndicate Bank debit card. I used it to withdraw money from ATM.” The plastic card offered him the convenience that wasn’t there when he used to withdraw money from the same bank before. “It was a lengthy process earlier. I used to stand in long queues to deposit a cheque or withdraw cash,” he recalls.

After two decades since Rao first used his debit card, the plastic money continues to amaze him. “I can now avail so many other services on the internet and pay for them by my card. I mostly pay my water and electricity bills and book railway tickets from IRCTC website with the help of my card. Booking railway tickets online is a satisfying service as it is tiring to go to the railway station. This change is good,” Rao says.

For Saurabh Bhatia, 35, plastic money is not only convenient but also a risk-free mode of transaction. As a businessman he keeps travelling across the country. And carrying huge amount of cash might pose a threat to him. “I deal in money during my business tours. It is easy to carry money in form of debit cards as it is safe,” he says. But that doesn’t mean he can do away with cash altogether. “I have to carry some change because not all places accept cards,” he adds.

Many offline merchants and e-commerce traders are also encouraging cashless payments by giving various discounts and offers to the consumer. For example, third party websites like Yatra and MakeMyTrip usually offer flight booking services with at least 10 percent discount if the ticket is booked from a card of a particular bank.

As of July, the number of debit and credit cards issued by various banks was around 69 crore and more than 2 crore, respectively, according to RBI. However, their usage may not be high as seen in Mohammad Umar’s case.

Moreover, cards have only a limited function in ushering in cashless economy. On one hand, retailers prefer receiving payments via cards rather than digital wallets, but on the other hand, plastic money is largely used to withdraw cash from ATMs. “You will find larger usage of debit cards at ATMs, not for making payments but for withdrawing cash,” says Surajit Mazumdar, professor of economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). In other words, plastic money is only adding – or returning – cash into the economy.

If we look at the RBI figure, the volume of transactions through debit cards at ATMs was 8,073 million in 2015-16, while usage at point-of-sale devices was only 1,174 million. It is perhaps because a majority of merchants do not have the infrastructure to accept payments via cards, especially in rural and remote regions.

“India currently has 1.2 million POS terminals, although there is a need for 20 million POS machines in a couple of years,” revealed Kant at the Digital Payments conference.

But with the rise of private players we are witnessing active participation in building the infrastructure. Oxigen, a digital wallet company, has recently tied up with RBL Bank. The company is developing a ‘super POS’ machine that will not only accept card and wallet payments, but will also help rural citizens having Aadhaar number to open bank accounts. “We are deploying super POS machines in Bihar and Odisha and elsewhere in the eastern parts of the country. This small device can work as a merchant payment device at a very low cost of Rs 1,000,” says Pramod Saxena, founder and chairman, Oxigen.

Such efforts need to be intensified. If there are POS devices even at small shops and kiosks then a consumer will not use his/her card just to withdraw money from ATMs.

But this convenient and comparatively risk-free mode has not proved to be a happy experience for some. Banks have reported close to 12,000 frauds related to credit/debit cards and net banking in 2015, communications and IT minister Ravi Shankar Prasad told the Rajya Sabha in February.

To curb such frauds the RBI has notified banks to replace existing magnetic stripe cards with EMV chip and PIN cards, which generate a unique transaction code every time it is used.

Internet/mobile banking

From checking bank balance to transferring funds through real-time gross settlement system (RTGS), national electronic funds transfer (NEFT) and immediate payment service (IMPS), electronic banking has brought banks at the doorstep of consumers. Internet and mobile banking have largely replaced cheques.

Adil Ali, 30, who works in HCL, says banking services such as IMPS have made transfer of money really quick and simple. “I use internet banking extensively. Most people in my network who are not comfortable using the internet ask me to transfer money on their behalf. They later deposit the same amount in my account,” he says.

Moreover, private banks allow customers to add new beneficiaries into their account instantly, which makes the transfer quick. But the same procedure is not smooth while dealing with public banks. “I have accounts in both private and public banks. SBI does not allow IMPS after 8 pm. Also, it takes at least four hours to approve a new beneficiary, while private banks do it immediately,” says Ali.

Keeping aside the perennial debate of public vs private banks, he agrees that internet banking has made money transactions simple to the extent that it is no longer needed to physically visit the branch.

Agrees Siddharth Singh, from Hazaribagh in Jharkhand, who doesn’t remember the last time he visited his bank. “I only go to the bank when I have to deposit cash in my account. For checking balance, viewing past transactions or making payments, I use internet banking,” says Siddharth, who is in his twenties.

Recalling the first time when he made an online payment, he says, “I was filling multiple forms for colleges in 2009 and for each form I had to go to my bank to generate a challan and then go back to the same college to make the payment.” One college gave him the option of paying online and it turned out to be a whole new experience for him. “It was really convenient. I did not have to go to the bank. I made the payment online from my home.”

This convenience is only going to increase with the launch of unified payment interface (UPI) by NPCI. It is seen as a game-changer in digital payment for the banking sector. UPI allows interoperability among banks to perform payment services like sending and collecting money through a single mobile application to any UPI-enabled m-banking app. Digital wallets, on the other hand, do not transfer money to wallets of different service providers.

“IMPS is now operated in UPI and the platform has 21 banks as of now. There are 100-plus banks that are participants of IMPS; likewise 100-plus banks have to come on UPI,” says Hota. “UPI is right now only for banks. But later non-bank entities should also become part of this.”

Mobile/digital wallets

They play a critical role in bringing the cash-driven economy onto the digital platform. Services offered by these wallets have increased manifold, from mobile recharges to cab services to utility bills payments and online and offline shopping. One can now even pay a school’s tuition fee through these digital wallets. When 30-year-old Roshini, a resident of Delhi, realised that she can pay for her milk purchase at the local Mother Dairy booth through Paytm’s digital wallet, she was pleasantly surprised. “It’s easy and I don’t have to carry change all the time,” she says. All she has to do is scan the Quick Response, or ‘QR’ code – a matrix of black and white squares storing URL information that can be read by a smartphone camera – displayed at the booth, and enter the exact amount to make payment from her Paytm mobile app. The retailer gets an instant remittance message.

Here the convenience of digital payment is not only experienced by Roshini as a consumer, but also by the retailer whose payments are directly transferred to his bank account on a daily basis. “Earlier I used to take cash and then deposit it in my bank account. Now it comes directly to the account,” says Ramesh Kumar, the Mother Dairy booth retailer. The proportion of customers, of course, making digital payments is really low, since the service started just a few days ago at Kumar’s booth.

Paytm, which is one of the largest digital wallet companies in India with a registered customer base of 12.2 crore, plans to extend this facility to more than 750 Mother Dairy booths in Delhi NCR. “Starting from the morning milk supply to all other everyday necessities, it is our mission to make everyday payments extremely simple. Working with Mother Dairy, we would be able to bring a seamless payment experience to millions,” Vijay Shekhar Sharma, founder and chief executive officer, Paytm, said in a press statement. According to Sharma, around 17 million people use the app every day.

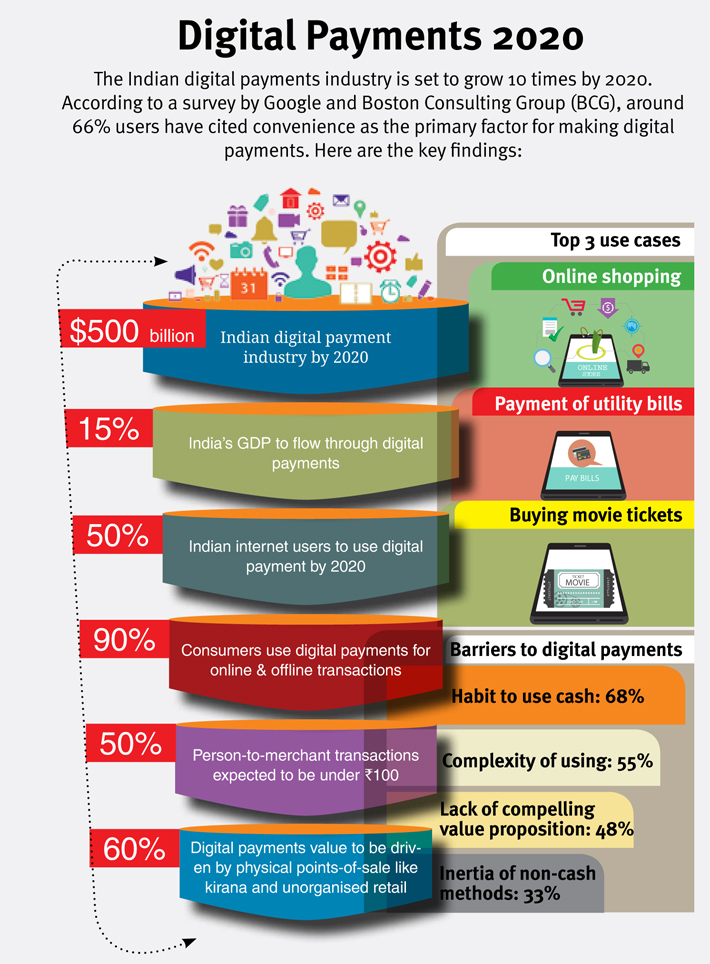

The mobile wallet market in India is projected to reach $6.6 billion by 2020, as per the ‘India Mobile Wallet Market Opportunities and Forecast, 2020’ report by TechSci Research. The most popular services availed through these wallets though are mobile recharges and bill payments, points out a Google-BCG study. “Initially, on an average, 45 million mobile recharges were happening in the country every day.

These recharges were fundamentally done in cash and bulk of them was done at kirana stores. Only one percent of transactions were done online,” says Sudeep Tandon, chief business officer, FreeCharge. Now, he adds, “Eight percent of transactions are happening online and the number of mobile recharges has gone up to 60 million, which is a direct result of digital wallets.”

One of the key reasons that mobile wallets are gaining popularity among consumers is that they allow small-value transactions on a daily basis with various discounts and offers. “We do 50 million transactions every month. We have 150 million customers who are doing these transactions. You cannot imagine a bank doing Rs 20 or Rs 200 transactions on a daily basis,” says Saxena of Oxigen.

He believes that having a transactional platform outside the banking system could be cost effective. “On an average, cost of a transaction can be one rupee or below in the digital wallet system. So not only you need to bring in the informal merchant into the system, you have to also create these transaction platforms which are out of the banking system,” he adds. Therefore, having more merchants accepting digital wallets as a payment mode contributes to the overall growth of less-cash economy. Saxena maintains that it’s not important to count the number of registered users; what is really important is the number of merchants who are capable of accepting payments through digital wallets instead of cash. “Our main focus is to increase our network of merchants to one million,” he says. On the other hand, Tandon says that in the next 18 months FreeCharge is planning to expand their merchant base to five million.

The rise of competition in the digital wallet sector is encouraging more merchants from the informal sector to shift towards formal transactions. This has been made possible through various factors such as low-cost smartphones and expanding reach of the internet.

Convenience plays a key role in driving digital payment. The Google-BCG report indicates that 81 percent of users of digital payment instruments prefer it over other non-cash modes.

Can India be fully cash-free?

The country is definitely making strides in moving to a cash-free regime, but can it banish hard cash fully, the way Sweden has? Industry observers believe that even though the electronic modes of payments play an enabling role in the move to a less-cash society, they have largely been restricted to the urban middle class and are seen as a matter of lifestyle.

For instance, the rise of digital-payment startups is definitely helping the economy to fuel the trend. But unfortunately, their reach seems to be limited to urban spaces, feels Anish Williams, co-founder and CEO of Udio, a Mumbai-based digital wallet company.

Meesho, a Bengaluru-based startup, helps small-scale retailers running their businesses on social media platforms like Facebook and WhatsApp, receive digital payments. Small sellers cannot afford cash-on-delivery, so they mostly transact via NEFT which is a time-consuming process. Meesho not only provides them an e-commerce like platform on mobile phones to manage orders systematically, but also gives them a means to collect their payments instantly through electronic modes like net banking and card payments. But obviously their services are restricted to the urban areas.

Williams further says, “A lot of fin-tech companies are largely focusing on super-banked consumers. So, for example, a person who has got a credit card keeps getting more and more convenient ways to make digital transactions. But a person who is transacting in cash is not getting any exposure to it.”

The fundamental problem comes with infrastructure and internet connectivity. According to the Census 2011, close to 43.2 percent of India’s rural households continue to depend on kerosene for lighting, leave alone internet connectivity. Of course, efforts are on to improve access to both – electricity and internet.

That is why Ajay Shah, professor, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), believes that “it is not yet time to get excited and declare success over cash”.

“We are very far from any plausible definition of success. For example, there is a study that shows if you divide cash in circulation by GDP, India is essentially number one or two in the world. So we are least effective in modernising our payment system. Most African countries are doing better than us,” he said at the conference.

What the government can do, he suggested, is to open the market to private and foreign players. “I was disappointed to hear that players like MobiKwik could not be a part of the UPI platform. We have structural entry barriers which take us back to that telecom era when DoT (department of telecommunications) would block your business and tell you what you can do and what you can’t. We should question every element of entry route. Google and Facebook are potential payment players in India. But they are not even trying to be in this space because of the licensing and regulatory framework, that we have been given,” said Shah.

Moreover, “the lever of policy should be in un-conflicted hands,” he added, giving the example of the telecom regulatory authority of India (TRAI). “The way we made progress in the telecom sector was by separating services and regulation. We got TRAI which is uncomplicated because it is not in the business. We got private players and foreign players and we got new technology.”

Vivek Belgavi, partner, financial services, FinTech and technology consulting leader, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), also hints at public-

private partnership in this sector. “We have 25-40 million merchants and less than a million are covered under POS channels. The private players should invest in acceptance infrastructure but the challenge is that the margins in this business aren’t so wide. The cost of doing this business is high and so is the chance of losses. Private interventions solely will not work.”

The infrastructure gap, meanwhile, can be filled with smartphones, to support merchants in accepting non-cash payments. There is a clear boost in the demand side of smartphones in India. In the first quarter of 2016, 23.5 million units of smartphones were shipped, registering 5.2 percent growth over the same period last year, according to tracker International Data Corporation (IDC). With the shipment of 15.4 million units in total in the first quarter of this year, smartphones supporting 4G technology have seen an interesting growth. Experts feel the growth is due to the expanding ecosystem for 4G smartphones. Even the emergence of Reliance Jio in the 4G smartphone market is seen as a big game-changer.

Krishnan Dharamrajan, executive director, Centre for Financial Inclusion, says, “In future you will simply need a mobile to make a cashless payment. The new mode of payment will make electronic transaction very cheap. A payment will not need any investment in infrastructure, but only a mobile phone. If two people have a mobile phone, cashless payment can be made.

“Also, if at the end of the year, taxpayers get some amount of tax break for making electronic payments, then that would only encourage cashless payments,” feels Dharamrajan.

Agrees Garg: “There are costs related to cash but it does not seem apparent. Unfortunately for non-cash methods, those costs are very clear in terms of merchant discount rate (MDR) charges and other electronic payment charges.” He indicated that those extra charges levied on electronic payment have to go, in order to make non-cash payment methods acceptable.

In February, the union cabinet decided to withdraw any kind of surcharge, service charge and convenience fee on cards and digital payments imposed by various government departments.

Moreover, the change shall begin from the government itself, feels Garg. “It [government] should first make all its payments including salaries through non-cash methods, which should also include mobile wallets. Other than payments, all the government receipts should be enabled by all non-cash methods.” He adds that by non-cash payment methods it does not mean only card payment system.

In fact the US Agency for International Development (USAID) in its research on cashless economy has claimed “consumers who are paid digitally are more likely to transact digitally”.

Incentives should be given to merchants too for accepting cashless payments. “Infrastructure to accept electronic payment via POS devices is not cheap and merchants need to be benefitted to use such gateways,” says Belgavi.

The RBI has decided to set up an acceptance development fund (ADF) to expand card payment infrastructure across the country. The IBA will form rules for contribution and utilisation of funds for the ADF. The framework for the ADF will be issued by December-end this year.

Along with infrastructure and incentives, Saxena feels that there is also a need to communicate the benefits of electronic payments. “The government has to really go down to communicate with people at the grassroots level. Their basic needs can be addressed better in that way. That level of communication is required.”

Amitabh Kant of NITI Aayog said at the conference, “The government issued licences to 12 [banks] in past 45 years. But in the last one year we have issued 23 banking licences. Moreover, 70 percent of the Indians are less than the age of 32. By 2040, India will keep getting younger and younger whereas the West will keep getting older. Since young people adapt to digital world much faster it is important to break all barriers towards realising a cashless and paper-less society in the coming years.”

[email protected]

(The story appears in the October 16-31, 2016 issue)