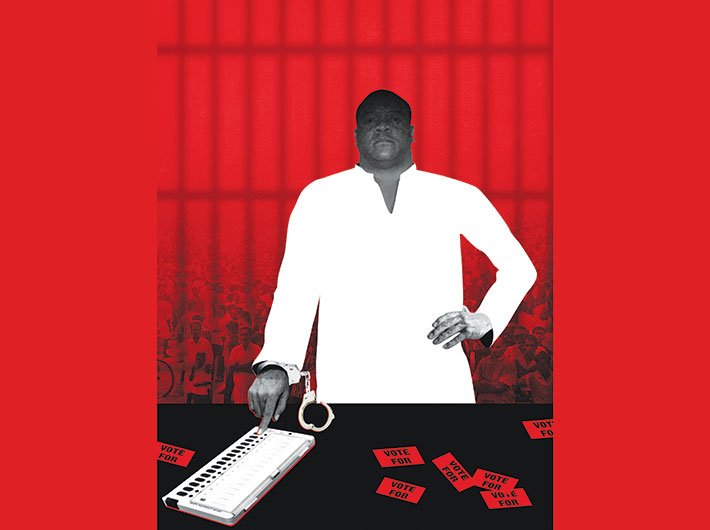

Criminalisation of politics is the focus of public debate when discussion on electoral reforms takes place. This issue gets amplified when data highlights an increasing number of candidates with criminal cases contesting elections. Candidates who win from jail bring out the stark reality of our electoral politics. The supreme court and the election commission have called out for a change in our electoral laws to prevent candidates facing criminal cases from contesting elections. The parliament has made some amendments to electoral laws to incorporate the orders of the apex court and recommendations of the election commission. However, the policy response to address the challenge of criminalisation of politics has been one dimensional. Only changes to the law have been made with the hope that it will solve this issue permanently. However, the changes made in the law haven’t worked so far. The reason is that there is a gap in their intent and their implementation. This gap then ensures that the purpose of the law is defeated.

The issue of the quality of candidates contesting elections becomes important because it is at the root of our governance challenges. Individuals we elect represent us in our legislative institutions and make laws that govern our society. What kind of individuals should they be? Dr Rajendra Prasad, president of the constituent assembly, reflected on this issue while moving the motion for the passing of our constitution. He said, “If the people who are elected are capable and men of character and integrity, then they would be able to make the best of even of a defective constitution. If they are lacking in these, the constitution cannot help the country. After all, a constitution like a machine is a lifeless thing. It acquires life because of the men who control it and operate it, and India needs today nothing more than a set of honest men who will have the interest of the country before them…It requires men of strong character, men of vision, men who will not sacrifice the interests of the country at large for the sake of smaller groups and areas…We can only hope that the country will throw up such men in abundance.”

The constitution does not specify what disqualifies an individual from contesting in an election to a legislature. It is the Representation of People Act which specifies what can disqualify an individual from contesting an election. The law does not bar individuals who have criminal cases pending against them from contesting elections. An individual punished with a jail term of more than two years cannot stand in an election for six years after the jail term has ended. If a lower court has convicted an individual, he cannot contest an election unless a higher court has overturned his conviction. Simply filing an appeal against the judgment of the lower court is not enough. In 2013, the apex court ruled that a sitting MP and MLA convicted of a jail term of two years or more would lose their seat in the legislature immediately. This judgment led to Lalu Prasad Yadav losing his membership to the Lok Sabha in the same year.

Critics point out, that the disqualification of candidates with criminal cases depends on their conviction in these cases. With cases dragging in courts for years, a disqualification based on conviction becomes ineffective. Low conviction rates in such cases compounds the problem. The Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) in their report from 2014 gave concrete numbers to this effect. According to their report, 30% of sitting MPs and MLAs were facing some form of criminal proceedings, and only 0.5% were convicted of criminal charges in a court of law. The law commission in its report on electoral disqualification in 2014 examined this issue. It deliberated on whether disqualification from contesting election should be triggered upon conviction as it exists today, or at the time of framing of charges by the court? It was of the opinion that, “disqualification at the stage of charging, if accompanied by substantial attendant legal safeguards to prevent misuse, has significant potential in curbing the spread of criminalisation of politics.”

The commission went on to specify some of these safeguards. One of them being that only criminal offences which have a maximum punishment of five years or more are to be included in this provision. The commission suggested that charges filed up to one year before the date of scrutiny of nominations would not lead to a disqualification. This safeguard would then minimise politically motivated cases from being filed against an individual before an upcoming election. It also suggested that in the case charges framed against sitting MPs/MLAs the trial should be conducted on a day-to-day basis and completed within a year. The election commission in its 2016 note on proposed electoral reforms agrees with the recommendation of the law commission. Last month, the supreme court in an order favoured the creation of special courts for expediting criminal cases involving politicians. The government has submitted that it will set up a dozen such courts.

However, neither the approach of the law commission nor the creation of special courts can work in isolation. These single-pronged approaches do not target the root of the problem. Data suggests that voters don’t mind electing candidates facing criminal cases. Voter behaviour then emboldens political parties to give tickets to such candidates who can win an election on their ticket. Simply creating a harsher law and ensuring a specialised court would not help. The harsher law will only result in undue political pressure on the judiciary to delay, derail or compromise the judicial process. Similarly, we have specialised tribunals and courts which have been formed to decongest the regular judicial system and expedite certain types of cases. But they have themselves become clogged. Any special court made to expedite criminal cases against sitting MPs and MLAs will face similar challenges. These special courts will also have to deal with the deluge of new cases coming before them as a new crop of candidates starts winning elections. In essence, a single-pronged legislative and judicial solution will not help reform the electoral system in this country. It will require attacking the problem on different fronts. Addressing the entire value chain of the electoral system will be the key to solving the puzzle of minimising criminal elements from getting elected to our legislatures.

This process would involve sensitising the electorate about the role and responsibility of the elected representatives. Currently, a large part of the voting population views their representatives as their problem solvers. So they are willing to vote for a candidate who can get things done ignoring his involvement in a crime. Viewing their MP and MLA as lawmakers will slowly change their perception of what they want from their representative. This then requires a fresh pool of candidates who can appeal to the voters by their abilities as good lawmakers with innovative ideas.

Political parties would then be pressured to give tickets to individuals who can win elections without having muscle power or criminal cases against them. But this would not be enough. Political parties will have to be encouraged to have stronger inner party democracy to attract this new set of leaders to join the party. And finally, our judicial system will have to be overhauled drastically to ensure that justice is dispensed swiftly in all cases. An efficient judicial system will then ensure the swift removal of individuals who transgress the law from the political system.

All these steps will have to work in parallel to remove the scourge of criminalisation of politics. If this issue remains unaddressed, then it will hollow out the foundations of our democracy.

Roy is the head of legislative and civic engagement, PRS Legislative Research.

(The article appears in January 15, 2018 edition)