Politics was always seen as a dirty game. But our inability to check the criminalisation of politics is a national shame.

Prof Jagdeep Chhokar of the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) points out a stark irony of crime in Indian politics. “There are more than 3.5 lakh undertrials languishing in Indian prisons today. Many of them have already spent more time in jail than they would if they had been convicted. We are not allowing them to vote. But there are politicians with serious criminal cases against them who continue to contest elections and make laws,” he says. If this irony persists, it is because, despite much talk of cleaning up politics, little has been done.

The supreme court, however, initiated a small movement in that direction on November 2, a swachhata abhiyan of sorts for politics. Acting on a petition filed by advocate Ashwani Upadhyay, a BJP spokesman himself, the apex court directed the central government to set up special courts to try within a year lawmakers facing criminal cases; it gave the government six weeks to submit a detailed plan for setting up such courts. A bench of justices Ranjan Gogoi and Navin Sinha also said the centre could not disclaim responsibility for decriminalisation of politics, saying law and order is a state subject. (On December 12, the government responded by saying it would set up a dozen such courts.)

Another plea from Upadhyay, however, was thrown out of court. On December 1, the court struck a loud note for both freedom of speech and the separation of powers of the executive, the legislature and the judiciary, throwing out his plea seeking to debar convicts from heading or floating political parties. The petitioner probably had in mind people like Lalu Prasad Yadav and Om Prakash Chautala, who have been debarred from contesting elections but continue to wield power through their parties. The bench comprising the chief justice of India, Dipak Misra, and justices AM Khanwilkar and DY Chandrachud asked why the court should decide on this and said the problem was something parliament and the government might consider looking at.

As far as Upadhyay’s first petition goes, though, the court said: “Setting up of special courts and infrastructure would be dependent on the availability of finances with the states...the problem can be resolved by having a central scheme for setting up of courts exclusively to deal with criminal cases involving political persons on the lines of the fast-track courts which were set up by the central government for a period of five years and extended further, which scheme has now been discontinued.” The petitioner had mentioned how government officials, right from the lowest levels to chief secretary level, were debarred from taking any official position if they were convicted in criminal cases. The SC clubbed this matter along with a follow-up of its own 2014 order where it had directed the government to make provisions for such cases to be heard within one year – specifically, those mentioned in the Representation of the People Act.

“How many of the 1,581 cases involving members of legislative assembly (MLAs) and members of parliament (MPs) (as declared at the time of the filing of the nomination papers to the 2014 elections) have been disposed of within the time-frame of one year as envisaged by this court by order dated 10th March, 2014 passed in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 536 of 2011? How many of these cases which have been finally decided have ended in acquittal/conviction of MPs and MLAs, as may be?” the court asked. The bench also wanted to know if any new criminal case had been lodged against any present or former MP or MLA between 2014 and 2017 and its status.

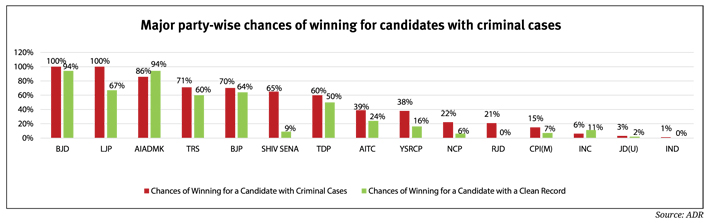

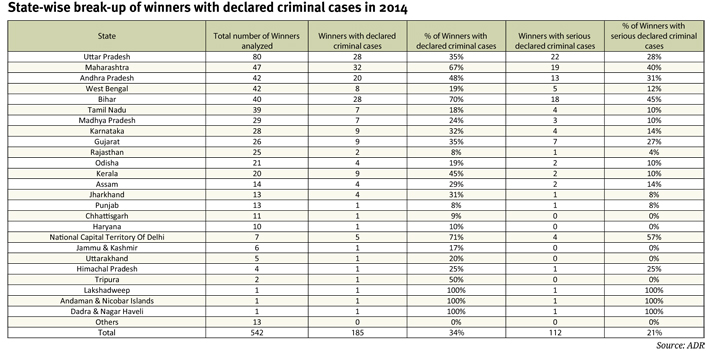

According to the ADR, a group that has been campaigning for cleaning up politics, there are 1,581 legislators, at both central and state levels, facing criminal charges attracting an imprisonment of over five years. The ADR 2014 general election results analysis says the BJP has the maximum number and the proportion of winning candidates with declared criminal cases – 98 out of 281 winners – comes to about 35 percent. There are 63 winners with serious declared crimes, such as murder, attempt to murder, communal disharmony, kidnapping and crimes against women. That is 22 percent of the total winners in the party. The proportion of candidates facing criminal and serious criminal charges for the Congress are 18 percent and 7 percent respectively. There are ten MPs facing murder charges – four come from the BJP, one each from the Congress, NCP, LJP, RJD and Swabhimani Paksha, and one is an independent elected representative. There are 17 MPs facing charges of attempt to murder – 10 are with the BJP, two with All India Trinamool Congress, one each from INC, NCP, RJD, Shiv Sena and Swabhimani Paksha.

“Taking people with criminal background out from public office will surely have an impact. It’s a sword hanging on their (lawmakers) head, it will surely act as a deterrent. It is a good beginning,” says Meenakshi Arora, a senior supreme court lawyer who represents the Election Commission of India in the SC in Upadhyay’s petition. “We need time-bound disposal. It will at least solve one part of the problem,” says SY Quraishi, former chief election commissioner, referring to long-pending reforms, including police and judicial reforms.

The cynicism prevails, however.

The decriminalisation of politics is yet another key reform that has been talked about for over two decades. The present and previous governments have voiced their commitment to decriminalising politics but have never matched it with action. When the apex court heard Upadhyay’s petition and directed the government to undertake corrective steps, it was not for the first time that it was taking note of criminalisation in politics, which is only increasing.

Historically, not just the SC but even law commissions and government- or court-appointed committees have spelled out corrective measures. Major reforms proposed are: tweak the Representation of People Act to debar politicians with tainted background and add provisions for the regulation of political parties to ensure financial transparency and internal democracy. But every time, lawmakers from across the political spectrum have come together to stall the implementation of any such order or report.

“A key reason is that the political parties consider themselves above law. They have forcefully subverted attempts to come under laws, even those passed by the sovereign parliament,” says Chhokar, a founder member of ADR. And former CEC Quraishi says, “I don’t know if the government will raise the resources required to bear the cost of setting up special courts or simply find reasons for not doing it.”

Ground for scepticism

There is reason for scepticism, even pessimism. Says Chhokar, “I’m sceptical for a couple of reasons. One, even if the government timely submits a scheme as directed by the court, it is doubtful to what extent it will be implemented in spirit. There have been similar orders by the SC in past. The Public Interest Foundation (PIF) case, which led to the 2014 SC ruling, is an example. A more poignant example is the Prakash Singh judgment – pertaining to police reforms: it’s been over 10 years. A mere SC order will not mean anything unless it is implemented.” He says the political establishment will never make it happen. “Two,” he continues, “through the setting up of special courts for 1,581 lawmakers, you are only dealing with the existing lot. Let’s assume you deal with these cases in two years. You will have another 1,581 two years later.”

The ADR was the petitioner in the landmark 2003 SC judgment directing public representatives to declare their income, assets and criminal background in their affidavits while filling nominations before elections. Before the judgment, there was no way to ascertain details about a candidate. “In economics, there is an argument of ‘flow and stock’. In dealing with black money, they did the same thing. Demonetisation dealt with the existing stock of black money, but you didn’t deal with the creation and flow of black money. Similarly, when you deal with these 1,581 cases, you deal with existing stock but you are not stopping the flow. The special courts will continue till eternity. Whereas if you pass a law, you are stopping the flow. The solution is there; the question is of willingness,” says Chhokar.

Prof Sanjay Kumar, director, Centre for Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), says, “There is no other way. Change the law. If the lower court convicts a lawmaker in a serious crime, then he should be barred from holding the position until a higher judicial court absolves him. The nature of crime has to be specified.” Also, when candidates do not share full details about their criminal cases in their election affidavits to the ECI they must be punished, says Kumar. As of now, the law doesn’t provide for a way to reinforce it.

Kumar is reiterating the two key recommendations related to electoral reforms of the justice AP Shah-headed law commission, which submitted its report in 2014. The existing provisions under the law (the Representation of People Act) provide for debarring of lawmakers only after they have been convicted. However, this provision has been grossly inadequate as trials go on for years and the conviction chances are minimal.

The law commission says that although the judicial mind is not applied while filing an FIR or a chargesheet, it is applied when the court frames charges. An adequate level of judicial scrutiny goes into the framing of charges and hence through disqualification at this stage, with some safeguards, Indian politics can be decriminalised.

In April, when the SC, while hearing Upadhyay’s petition, sought answer from the government about what it is doing with the law commission report, the government said it has formed a committee of senior officers to look into the matter. “The respondent is conscious of the need for electoral reforms in our country. However, electoral reform is a complex, continuous, long drawn and comprehensive process and the Union of India through legislative department is taking all possible action to deliberate upon measures of electoral reforms required in our country through various forums like consultation, meeting, etc. with all stakeholders,” the law ministry responded. It termed the idea of setting up special courts to try MPs and MLAs as ‘unwarranted’ as long as the cases are heard within a year, as prescribed by the SC earlier.

According to a senior official at the election commission, the law ministry is simply sitting over the recommendations. “A few months ago we sought information on what the ministry is doing with the law commission report, but it didn’t respond. We are aware that no action has been taken further by the ministry,” says the official, requesting not to be named. “Isn’t it simple? Why would politicians make a law that would hurt them the most? Apne hi pairon pey kulhadi kyon marengey?”

A helpless EC

The election commission, it might be noted, only has the power to register political parties; it cannot deregister them. At present, there are roughly 2,000 parties registered, yet unrecognised, with the ECI. “Several small parties are created only for money laundering. They register as a party and automatically get income tax exemption,” the official says. Political financing has become more opaque with the recent introduction of electoral bonds: any private person or organisation can go to a designated bank, buy an electoral bond, and deposit money in a given account without disclosing his identity. The bond can be redeemed by political parties within four weeks. Jaitley, in his 2017 budget speech, had said, “Every recognised political party will have to notify one bank account in advance to the election commission and these [bonds] can be redeemed in only that account in a very short time. These bonds will be bearer in character to keep the donor anonymous.”

The election commission has been getting annual income statement from parties, wherein they would disclose details of funds – of over '20,000 – they received from any private person or organisation. “However, under the proposed electoral bonds initiative, the parties won’t disclose information about the bonds in their annual returns,” the election commission official says. The ADR filed a petition in the SC in the first week of November challenging the proposal of electoral bonds.

“It’s a very bleak picture,” says Sanjay Kumar of CSDS, adding that the criminalisation of politics may continue in the coming decades. According to Kumar, a reason behind this cynicism is voting preference of the electorate. “People vote mostly on identity. They don’t care for candidates. When they do they would prefer a candidate who would get things done for them, irrespective of his background,” says Kumar.

It has now become a vicious cycle. Milan Vaishnav, director and a senior fellow at South Asia programme at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, in his book When Crime Pays, talks about the failure of the Indian state to provide basic service to its people and hence the emergence of the bahubalis – the Robinhood figures. For Kumar, change or reform should come from political parties; and that would happen only when people demand it. But Chhokar thinks otherwise. “Just make a law,” he says. “Can’t you find 543 people with a clean background in a country of 1.28 billion people?”

Finding right candidates

Political parties will keep giving tickets to tainted politicians, saying that people could choose not to elect them. But Chhokar says, “They get elected because people don’t have a choice.” According to the ADR, on average more than half the constituencies are such where at least three candidates have criminal cases against them. Roughly every constituency, says Chhokar, may have 25 contestants. But how many of them will really have chances of winning? Two or three, on an average. So why would people vote for a candidate whose chances of winning are anyway less? People don’t have a choice.” An ADR analysis shows that in constituencies where the number of tainted candidates is less, there are chances of candidates with a clean background getting elected.

“Before every national or state election in the last 15 years, the ADR has written to political parties, appealing them to not allow candidates facing criminal charges from contesting elections. Post elections the ADR writes back, requesting the winning party (or parties) to not make the tainted elected representatives ministers, yet the parties crown them too,” Chhokar says.

In 1999, the law commission strongly proposed regulations for governance of political parties. Later, a committee headed by former chief justice MN Venkatachaliah prepared a draft legislation on the functioning of political parties. The draft bill, which was put out in 2011, has been there since.

The committee borrowed heavily from the German constitution. After the World War II, Germany was completely shattered. “The German society realised that the rise of Hitler happened through a legitimate route and later he acquired so much power again through a legitimate route,” says Chhokar. So Germany rewrote its constitution and added a chapter on the functioning of political parties. Will the people and the political parties of India take a lesson?

pratap@governancenow.com

(The article appears in January 15, 2018 edition)