Maharashtra developments can leave voters unsure of where, by whom and for what purpose their vote will be used

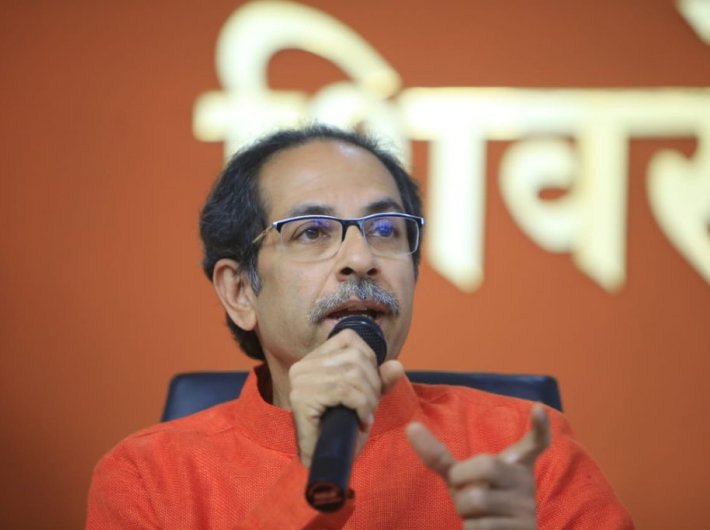

On November 29, Uddhav Thackeray, the 19th chief minister of Maharashtra and the leader of the Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA), won the vote of confidence in the 244-member Vidhan Sabha of Maharashtra. With this the month-old drama over the government formation in the state came to an end. The appointment of the MVA government under Uddhav Thackeray and events over the last month raise many crucial questions about the emerging contours of Indian politics. These questions go beyond the issues of morality, which for long have been abandoned in favour political pragmatism. Institutional structures and propriety that provided a fig leaf for deception were cast aside, way back in the 1960s. The important question now is: Are we witnessing the end of ideology in Indian politics? Or is it the beginning of pragmatic, interest-based, development-centred coalition politics? Does people’s mandate matter in the emerging patterns of coalition politics in India? How is popular mandate to be interpreted and operationalised, when ideology is no longer important?

There is nothing new about coalition politics in India. From the time of the Janata party government in 1977, when a disparate group of parties came together on the plank of anti- Congressism to the more recent examples of JDS-Congress coalition in Karnataka and BJP-PDP coalitions in the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir, there are numerous examples of coalition governments both at the centre and the state. In fact, between 1989 and 2014, India did not have a single party majority government at the centre. The rise of parties based on caste/religious lines since the 1990s marked a shift toward a kind of accommodative politics that was different from the internally grand-coalitional politics practised by the Congress. Both the UPA and the NDA government were coalitional.

Nor are ideologically incongruent coalitions new. One need not go far back into history. The BJP-JD(U) coalition in Bihar and the BJP-PDP coalition in Jammu and Kashmir are more recent examples of such coalitions. But by and large, coalitions where parties are ideologically similar and where there is asymmetry in terms of seat strength are more stable than those where all partners are of equal strength. Take the case of the BJP-Sena government in Maharashtra in 2014 or the Akali Dal-BJP government or even the BJD-BJP government in Odisha, which have lasted their full term.

However, prior to 2014, most coalitions at the state level had the regional parties as the dominant partner, while the national parties, be it BJP or the Congress played second fiddle. The BJP’s stated goal of a “Congress Mukt Bharat" is, as Suhas Palshikar observes, one of increasing its electoral dominance, but is, more importantly, a battle of ideas. The regional parties are the next in the BJP’s line of action. The BJP’s ascendance has challenged the gains of coalition politics for regional parties. This has created considerable unease among the regional parties. It is in this context, that we need to understand the developments in Maharashtra.

Though the Sena had formed a government in coalition with the BJP in 2014, this is the first time that Sena has come together with its former arch rivals, the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and the Congress, relegating its ally of three decades and its partner in the election, the BJP, to the opposition. The ideological incongruity of the three partners apparent in the formation of an MVA government is “indefensible in ideological terms” and its contradictions are apparent even in the Common Minimum programme (CMP) that was chalked out after three weeks of hectic negotiations. The preamble of the CMP says, “The alliance partners commit to uphold the secular values enshrined in the Constitution. On contentious issues of national importance as well as of state importance especially having repercussions/consequences on the secular fabric of the nation, the Shiv Sena, NCP and Congress will take a joint view after holding consultations and arriving at a consensus.”

The CMP itself marks a major departure for both the Shiv Sena and the Congress in terms of the politics that they have practised so far. It will not be easy for the Sena to reinvent itself as a development-oriented party and depart from its Hindutva worldview or for the Congress to ally with one of the early practitioners of the ‘sons of the soil’ movement and Hindu nationalism without losing out on its support base elsewhere in the country like in Kerala or Karnataka, where it aggressively plays it secular credentials. At a more pragmatic level, the issues such as the National Register of Citizens and Citizenship Amendment Bill, Uniform Civil Code, relationship with parties such as TMC, are some issues that can potentially bring the partners into conflict.

Daniel Bell, an eminent scholar of Harvard University, had pointed out that in the Western world where there was a “consensus among intellectuals on political issues: the acceptance of a Welfare State; the desirability of decentralised power; a system of mixed economy and of political pluralism. In that sense the ideological age has ended”. Fancis Fukuyama in the 1990s carried forward the argument and pointed out that if history is imagined “as the process by which liberal institutions—representative government, free markets, and consumerist culture—become universal, it might be possible to say that history had reached its goal”. The fault line of politics, he argued, would no longer be ideology; it would rather be cultural. Do the developments of Maharashtra signal the decline of ideology in politics?

The BJP, the Shiv Sena and the Communist parties could be regarded as few of the parties that emerged as adherents of ideology. The Congress too was ideologically rooted to a centrist position well till the 1980s. The Congress and The BJP occupied the two ends of the political spectrum in the loose bipolar politics of the 1990s with little possibility of compromise between them. One may recall how after the 1996 general election, the BJP had emerged as the single largest party in the Lok Sabha. Though Vajpayee was invited by president Shankar Dayal Sharma to form a government, he had to resign after 13 days in office, as his government was unable to muster numbers.

In the post-liberalisation period, barring the Communist parties, all parties converged on economic policies. However, with the rise of regional forces, ideological positions became more fluid. While both the BJP and the Congress had their own set of allies, there were a few parties that moved across the political spectrum. The DMK and AIADMK have been part of both the Congress-led UPA and the BJP-led NDA at different times. The Mayawati-led BSP formed government in alliance with BJP in 1996 and 2002 in Uttar Pradesh.

It is, therefore, not compromise on ideology that is at question. The point here is the fact that a political and opportunistic alliance often compromises the mandate given by the people. This was most apparent Bihar in 2015 when the JD(U) and RJD came together to fight the election and formed a government in Bihar, but later the RJD pulled out of the alliance and the Nitish Kumar-led JD(U) continued in office with the support of the BJP. In Maharashtra this time, the mandate was for clearly for BJP and Sena to form the government and the NCP and the Congress to sit in opposition. All the parties across the ideological spectrum not only violated the mandate but even justified the violation. The Shiv Sena projected itself as a victim of an aggressive and expansionist policy of BJP led by powerful central leadership. It has portrayed the BJP as a petty-minded party unwilling to accommodate its old ally and justified its alliance with arch rival NCP in the interest “people of Maharashtra”. The Shiv Sena’s entire campaign had centred on opposition to NCP.

Notwithstanding the hurried grab for power in violation of norms, the BJP has tried to claim the moral high ground out of the Sena’s demand for chief ministership as lust for power and its subsequent alliance with Ajit Pawar. The NCP has projected itself as the reluctant claimant of power, while the Congress saw merit in keeping the BJP out at any cost to protect the nation and its secular credentials while allying with the other Hindu nationalist party. The CMP and the interest of the “people of Maharashtra” are constructed alibis and CMP is propped up as an institutional mechanism to justify both the violation of mandate and compromise on ideology.

It is not the first time that this happened, nor is it going to be the last time. But it is the brazen violation of mandate, in development-centred politics that should be a cause of concern to Indian politics. Situations such as that of Maharashtra bring home the importance of ideological commitments in choice-based, participative democracy. In the long run, coalition bereft of ideological moorings and mooted on weak structures of development politics will weaken the prospects of coalitions. It will leave voters unsure of where, by whom and for what purpose their vote will be used. This will also weaken the faith in democratic institutions in general and franchise in particular, which has been by far the greatest success of Indian democracy.

The greatest challenge to the democratic structure is to restore the centrality of the mandate in coalition politics that have moved beyond ideological divide.

Dr. Manisha Madhava is Head & Associate Professor, Post Graduate Department of Political Science, SNDT Women’s University, Mumbai.