In November 2015, Mumbaikars started an exciting experiment. Called Equal Streets, it was a citizen initiative to usher in equality at least in the usage of roads and streets. Thus, on Sunday mornings, walkers and cyclists would have a 6-km stretch of an otherwise busy road in the upscale locality of Bandra to themselves. For a few hours, the road belonged to people instead of cars and cabs. This led to pleasant scenes. Like two kids sitting down on the road and sketching faces on the asphalt surface with colour chalks, joined by their mother who too was engrossed in doing the same. Some people cycled, those who could did yogasans, others played carom and most made new friends.

On the inaugural day, close to 15,000 enthusiasts had come out. Unfortunately, the initiative did not last long. But by January 2016, when it was called off – for lack of support from the traffic police as it added to their work, as many as 50,000 people had preferred to spend their leisurely Sunday mornings on the road.

They had made their point: that the authorities should pay attention to the need for ‘continuous and well-maintained footpaths and non-motorised transport-specific infrastructure’. In India, every city and town practises a kind of caste hierarchy on roads, where trucks, vans and bigger cars push away smaller ones, the driver of which in turn can scold a two-wheeler rider, and cyclists and pedestrian have to live in the mortal fear of them all. Footpaths either don’t exist or when they do vehicles are parked there and vendors set up their little shops in between. Also in the process of disappearing are public open spaces (now known by the acronym ‘POSes’), where dwellers of the same city can interact with one another and give the city a life.

This was not the first time Mumbaikars came together for such a cause. In 2012, transport expert and environmental activist Rishi Aggarwal, along with like-minded friends, started The Walking Project to transform the walking experience on seven arterial roads in the SEEPZ special economic zone (SEZ) of Andheri East. It, however, could not progress as funds were difficult to come by.

“Walking anywhere in Mumbai is a very unpleasant experience. Where is governance when you are not able to provide basic right of footpaths for walking?” asks Aggarwal. He blames it on the lack of political will as well as of social will. “There is lack of social engagement on the issues of dust, walkability, waste management, etc. Instead, there is public apathy towards it; especially from the upper middle and rich class,” he says.

For office-goers, the traffic conditions during the daily commute often define their mood and productivity in the office. The commercial hub of SEZ in Andheri East has a daily floating population of about one lakh employees, and when they all scramble to reach the workplace in their various vehicles, chaos is bound to ensue.

GN Photo

Feroza Suresh started Smart Commute Foundation there. The foundation planned to have a common point of origin for transport for all employees of the IT Parks of SEEPZ, Nirlon Park and Mindspace at Goregaon. She says, “We have been in talks for inculcating the habits of carpooling and cycling within the short commute and while we are ready to work here someone has to take the onus of funding which can come from corporates or authorities.”

Every day, close to five lakh people (equal to the population of a small city) walk to and fro between the suburban railway station and their workplaces in the central business district (CBD) of Lower Parel, Elphinstone Road and Dadar in the heart of Mumbai. Commute options in such districts should have been welcome, but when the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) gave the city its first and only 16-km cycling track on the CBD of Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC), it failed. Reason? No feasibility study had been carried out before the project. Result? The track was used for parking cars and bikes.

It is not the case that people do not want to walk or ride a bicycle. They do walk the first and last mile. Data shows that 51 percent people in Mumbai walk for various purposes. Sixty percent public-transport journeys necessarily start and end as walking trips. More than 80 percent of walking trips to work places or schools are of less than 15 minutes. Walking and cycling are not only cheap, convenient and ecofriendly modes of transport with last mile connectivity but good for health too. Yet, Mumbai lacks right setup for walking.

“In Mankhurd where we work every day the HDI [human development index] is 0.2. They are worse off than rural people. Doctors advise people to walk half an hour every day. But where can we walk?” says Anita Patil Deshmukh, executive director, Partners for Urban Knowledge and Research (Pukar), an independent research collective.

GN Photo

“There are no policies for spaces. Pedestrian lives are cheap in our country, so pedestrians are not allocated walking space. You need policies with penalties, which don’t exist,” she says. Feroza adds, “Thirty- five percent of the population that works within a distance of 7-8 km of the work place can walk or cycle to work, yet they commute by public transport or auto rickshaws, hire app-based taxis or take their own cars, adding to the traffic and increasing pollution.” Feroza frequently participates in the European Cyclists’ Federation’s Velo-City conference series in Amsterdam, where she says there is often space crunch for bicycle parking even after filling up four levels of underground cycle parking.

When it comes to the size and population of the city, various figures are offered, considering the municipal area alone, or the greater city. The landlocked city of Mumbai has an area of 603 sq km and population of 12.4 million making it the most populous city in the country. It has a density of 20,482 persons per km. The World Economic Forum citing UN Habitat Data says Mumbai has 31,700 persons per square km.

The 62 flyovers and the Bandra-Worli Sea link that came up in the last decade carry more cars than pedestrians. The sea link carries 37,336 vehicles daily, including city buses, against the eventual projection of 1,20,000 vehicles. Poor public transport, increasing cars and traffic jams, coupled with more and more roads that facilitate cars instead of people have brought Mumbai to a standstill.

With rising urbanisation, the focus the world over is on making cities better planned and better managed, with more investments in public transit systems, increasing green areas, use of parks and streets as public places for walking, cycling and electric cars. India, however, is yet to change its attitude.

VK Pathak, former chief, town and country planning division, MMRDA and dean of planning at CEPT University, Ahmedabad, agrees that city systems are becoming more car-oriented, but feels that reversing the trend poses practical problems. “Symbolic [space for] cycling is different, but how will you do it in a citywide cycle network in Mumbai?” Referring to Mumbai’s new Development Plan, in preparing which he played a key role, he adds, “When we did the DP initially we said that there must be right of way for pedestrians, making it mandatory to create footpaths. Any change in that would mean a change in DP. But they [executing authorities] do it. They keep on narrowing footpaths. People will continue to walk on streets.”

Leo Saldanah, founding trustee, Environment Support Group, says Indian metros are among the worst in the world when it comes to road space and traffic density. “Everyone has a right to buy vehicles, but that does not mean you encroach on the cycling and walking space. There has to be equity in planning and ‘elitization’ of planning has to go. Today people feel unsafe to walk or cycle on streets. We are rushing into big problems with road rage.” He thinks India is imitating the wrong models of the US and not learning from European cities which are making it easier to walk and cycle. Deshmukh would add the example of Singapore and Hong Kong, which are landlocked like Mumbai but have strict rules about add cars to the city roads. “Unlike in Singapore, our policymakers have not introduced congestion tax, carbon footprint tax, etc.,” she says.

Securing open spaces

Resident associations are up in arms opposing a new policy of the Brihan-Mumbai municipal corporation (BMC) to create 85,891 hawking pitches in the city. Nayana Kathpalia, trustee of an initiative called NAGAR which has been fighting for preservation of open spaces, fears city footpaths may not be walkable anymore. “BMC must map each section of every ward and remove encroachments and hawkers wherever possible to make footpaths walkable,” she says. “What is a smart city without a planner? The BMC did not have one till a few years ago,” she adds.

GN Photo

GN Photo

Debi Goenka of the Conservation Action Trust, who is a resident of Hiranandani Gardens, a self-contained community in Powai, where 2,000 hawker pitches will come up, says, “The locality has well maintained pavements, gardens and landscape. It is maintained by the builders and not the BMC. Now with 2,000 hawker pitches to come up here residents are at war with BMC.”

Elsewhere, citizens groups are opposing construction of eight infrastructure projects in and around Sanjay Gandhi National Park, a forest ridge, and demanding repossession of open plots handed out on lease and now in private possession of clubs and gymkhanas run by politicians and builders – and thus out of reach of the common man. These plots total 17 percent of the public open space left in the city. This appropriation of POS reduces per capita open space to a mere only 0.8 sq m.

Sayli Udas Mankikar, a fellow at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and a co-author of its report, ‘Endangered Future of Mumbai’s Open Spaces’, says that we are grappling with the challenge of putting basic infrastructure in place and things are not going beyond that. She adds that attempts have been made earlier to connect the three big grounds of south Mumbai, Azad Maidan, Oval Maidan and Cross Maidan, which are in close vicinity of both the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST) and Churchgate stations of suburban rail. “Now with the Metro passing along the route, it is an excellent opportunity to integrate and link these spaces and have a walk though from a garden into the metro or to the suburban railway stations and vice versa.”

The report, released by Maharashtra chief minister Devendra Fadanvis in October, criticises the BMC for allocating merely 1.3 percent of its annual budget for open spaces. (As for pedestrians, the effective allocation is 0.5% for pedestrians in its 2018-19 budget. Milind Mhaske, project director, Praja Foundation, fees, “It shows their concern for pedestrianism.”)

“No policy to date has spoken of holistic management of POS,” the ORF report says, adding “There is an urgent need to seamlessly integrate the planning and management of all built and inbuilt public spaces including footpaths, promenades, beaches, public markets, public monuments of art history and culture and the grossly underutilized and neglected waterfronts and river banks of the city irrespective of ownerships and jurisdictions.”

“At present,” Goenka says in the same vein, “people like us are fighting to protect the existing open spaces. There is no talk of creating open spaces except through environmentally destructive process like reclamation as it has happened in south Mumbai and BPT [Mumbai Port Trust] area without a thought for ecological and environment dangers. BMC is the richest civic body in the world; yet when it comes to green spaces they want people to come and adopt them. It is the politicians and builders who adopt them.”

Ashok Datar of Mumbai Environmental Social Network (MESN) which converted an abandoned POS in Mankhud into a playground with some funding from UN Habitat, says Mumbai has good rainfall and a huge number of open spaces lying in neglect can be turned around by BMC along with citizens organisations in a cost-effective manner.

Enhancing streets and safety

‘Peddling Towards A Greener India: A report on promoting cycling in the country’ prepared by The Energy and Research Institute (TERI) says that in 2012, nearly 80 percent road accidents were due to the fault of the drivers of motor vehicles; only 1.2 percent accidents occurred due to the fault of cyclists. As for the receiving end, 57 percent of those who die in road accidents in India are pedestrians. A World Bank report of last year, ‘The High Toll of Traffic Injuries; Unacceptable and Preventable’, estimates India’s national income would rise by 14 percent 2038 if it could manage to halve the fatality rate in road accidents.

Courtesy: WRI India

Courtesy: WRI India

“Principles of equity and democracy apply to pedestrians and cyclists who need to walk on safe roads,” says Ashar. “Motorists do not respect cyclists. Though MCGM [Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai] has a policy of Pedestrian First, there is no implementation. Streets are the largest network of public spaces. Is there any planning to save these lives [lost in road accidents]? In the safe systems approach, designers and planners must recognise that humans make mistakes and therefore they design ‘forgiving systems’.”

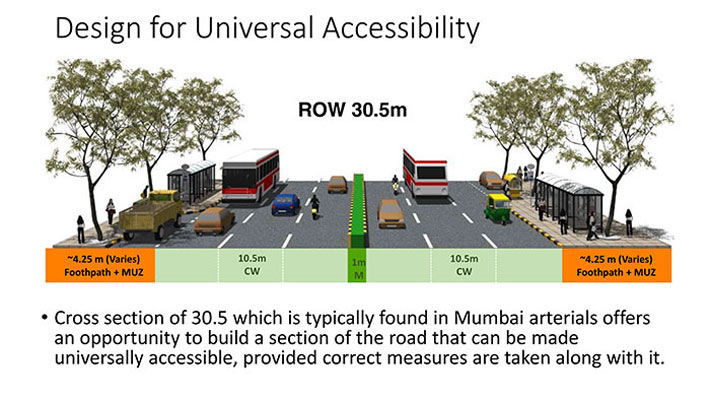

Dhawal Ashar, managing associate, urban transport and road safety, WRI India, says, “Indian cities are designed on the basis of the Indian Road Congress Codes and therefore we are designing cities as per highway standards. We need city-specific urban design manual and codes for cities with the following agenda: complete the network, design for universal accessibility and multiple capacity. Parking and hawking are parallel economies that need to be tackled for holistic development of the city. Today it is acceptable to park cars on roads whereas it is public space and parking is allowed for free. Parking has to be off street, at public space and paid.”

The way forward

To turn Mumbai into green urbanity, Datar of MESN has a few suggestions: (a) remove encroachments for unrestricted flow of city buses with more bus services and lanes, (b) have a bus stop within every kilometre, (c) two car-parking facilities should not be closer than a kilometre, (d) at least 50 percent space of each road must be used for city buses, as against 5-10 percent today, and (e) cycling should be promoted with safety, free parking lots for users, and free bicycle ride facilities stops outside all railway stations. Additionally, short-distance fare for autorickshaws and taxis should be higher and long distance should be cheaper.

“Having too much of asphalt, steel, cement and building roads is not good for a city. It causes cars to be driven and parked and becomes a mess,” he says. “We need to de-facilitate cars and reduce parking spaces, increase road tax from 10 percent to 25 percent. As against Rs 10 crore revenue from parking fees at present, we should aim at revenue of Rs 1,000 crore from parking within two-three years. This will reduce the number of cars, and enable revenue for good quality roads,” says Datar.

Homes near offices

Having workplaces closer to residences not only brings down traffic and the number of cars but also reduces pollution. Amita Bhide, dean of school of habitat studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), gives the examples of BKC which was initially developed as an economic hub now has a few residential localities being developed though it serves only top echelons – government officers, workers and those working in banks and other business establishments are not living in the neighbourhood at all.

She is also conscious of the fact that a city also has a legacy and you cannot rework the entire city in a short time. Having residences close to business districts will create hubs of pedestrianism and cycling, but that cannot be done for the city as a whole in a short time-frame. “Existing environments need to unravel and worked at progressively with clear commitment. For this you need long-term and short-term plans, some consistency in policies that speak to each other. At present policies don’t see in the same direction.”

Institutions and implementation

Urban planner Prachi Merchant, currently involved in the Revision of Draft Development Plan 2034 of MCGM, argues that Mumbai is a very complex city, puts the onus of implementation of well-intentioned policies on institutions.

“While it is nice to say ‘holistic’ and ‘comprehensive’ on paper, are we really systematically comprehensive when we are not institutionally geared up to the 21st century urban-planning principles? Today we have multiple institutions working towards a single goal but mechanisms are extremely scattered.”

Mumbai is a very high density, multi-layered and complex urbanity where every ward is a city in itself, she says. “In the DP we have made provisions for pedestrianisation and cycling but we know it has to happen at the ward level in a proactive manner. There are multiple stakeholders – citizens, government, urban planners ... Not just on paper, the mapping has to be done on ground with ward officers, licence department, traffic department and so on. It can happen but in a piecemeal manner and not holistic. It has to come from the state. Though we know our requirements and know how to turn things around, it has to be a system overhaul and it has to come from the central ministry, percolate down to the state and down to the corporation to the ward level.”

As an example, she mentions that if Equal Streets were to take place every day it’d require a huge effort. “Even if a particular commissioner supports it, what happens when his tenure is over? The system is not yet ready.” Merchant also cautions against comparing Mumbai with other cities and, “Some of the fantastic systems applicable in other cities may not fit well in Mumbai. We need to contextualize concepts from other countries to see if they are applicable with our systems.

While we have many lessons to learn from Singapore, it is authoritarian governance,” she says.

Mumbai’s leading builder Niranjan Hiranandani too says that creating walking and cycle tracks in the city will require a major change in the mindset of the powers that be as well of the residents. “At Powai in our project, Hiranandani Gardens, we have made provision for walking spaces as also cycle tracks. That was factored in right at the conceptualisation stage which is why it is still in existence despite the heavy demand in terms of traffic on the internal roads. We followed the same principle at our other projects in Thane, Panvel and Chennai.”

Courtesy: WRI India

Courtesy: WRI India

Concurring with Merchant and Hiranandani, Rakesh Kumar, director of the National Environment Engineering Research Institute (Neeri), says Mumbai has to move beyond greening one or two lanes and take the credit for it. “In Delhi they set up an authority [Delhi Parks and Gardens Society] headed by a senior IFS officer which is now managing 20,000-odd parks and 10,000 green localities with all agencies coming together to adopt the UTPITEC [Unified Traffic and Transportation Infrastructure (Planning and Engineering) Centre] guidelines on footpaths and greenery. Mumbai too needs microplanning right at the ward level. Green spaces and visitors corridors need to be created around spaces missing in Mumbai. A separate authority needs to be set up for greening Mumbai which cannot be done by the garden superintendent.”

Retrofitting streets

How do we solve mobility problems? Madhav Pai, India director, WRI, advocates ‘tactical urbanism’, which would have, among other things, roads redesigned for slower streets to make spaces and junctions safer for bicyclers and walkers. He recommends the ‘Less than 40’ approach, which means no street should be wider than 40 metres and vehicles should not be moving faster than 40 km per hour. This can shift people to walking, bicycling and public transport.

Pai has the example of New York in mind. Using tactical urbanism, the heavily congested city fixed itself slowly, working junction by junction and street by street. It started with temporary facilities for people to safely cross roads using features like raised crossings and bollards. Gradually they were made permanent. This model has been adopted by many European cities. Thus, about 15 percent New Yorkers prefer cycling even in temperatures ranging up to 15 degree below zero.

The city has reduced the speed limits of all roads to 30 miles per hour in the last 10 years.

Working on the same lines, WRI has taken up a Junction Safety Improvement Programme along with MCGM and Mumbai Traffic Police on the busy SV Road- Linking Road junction and Nagpada junction. With small changes, junctions can be redesigned in two years.

Having a footpath along the road reduces construction cost as compared to the carriage way that requires expensive material and more strength. Existing roads can be tactically designed at less than 1 percent of the cost [of road construction] for initial demonstration. “If a footpath is absent or obstructed, people will walk on the vehicular carriage way. Maintaining a continuous footpath across the length of the street can not only help pedestrians but improve traffic efficiency as well capacity.”

Demand space, push greening

Darryl D’Monte, chairman emeritus of the Forum of Environmental Journalists in India and founder president of the International Federation of Environmental Journalists, says that culture and momentum have to be created to demand space. “To begin with, even if streets are reclaimed for exercise on holidays and Sundays it will send a clear message that streets are not only meant for cars,” he says. Pai adds here that events like Equal Streets need to be done on a longer stretch, with a length of 60-70 km, so that people can get a feel of bicycling over a distance and then start demanding it. If such programmes add to the traffic police’s burden, it would be better that the municipality’s garden department or the state’s tourism department come forward with their resources, he suggests.

Hiranandani feels that disruptive and out-of-the-box solutions will click in Mumbai. He thinks the planned coastal road can include space for a jogging/ cycling track with green spaces. While spaces below flyovers are being converted into green spaces, more greenery can be created if we ensure open spaces are reserved for greenery, walking and cycle tracks during redevelopment.

Promote public transport

Mhaske believes Mumbai should learn from China and other countries and refocus policies to encourage public buses. “Convert BEST [BrihanMumbai Electric

Supply and Transport Undertaking] buses into AC buses, encourage private players to ply from selected start points to end points, have a regulatory authority, make it a public corporation, list it on stock exchange and take it out of its [BMC’s] control,” he says. “Rather than giving priority to the Rs 1,500 crore costal

road allocated in the current budget which will be used by 200,000 cars at its optimum level, the government can buy 1,000 AC solar-powered buses which will be used by a very large number of people.” He says that there must be a single transport authority for the entire Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) and the BEST committee can be converted into a separate transport committee for the city.

Ashar too says that when land prices are so high, giving free space to park cars is “the largest subsidy ever”. “In comparison, BEST is running on losses. The city administration can revive its buses. A bus can carry 79 people and it would require 60 cars to move the same number. Approximately 30 percent trips are short trips that can be done on foot or bicycle and can reduce 30 percent traffic on road. If buses are rationalised another 20 percent traffic will reduce on roads.” The traffic problem can be solved overnight if on-street parking is stopped. “It needs comprehensive thinking,” he says.

geetanjali@governancenow.com

(The story appears in the April 30, 2018 issue)