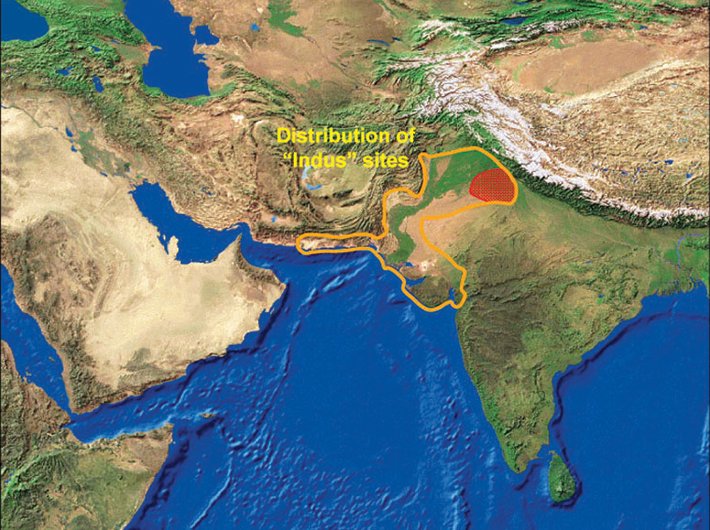

Was climate change responsible for the end of Indus Civilisation, or is there something more than meets the eye?

Heard of Rakhigarhi? It is a village in Hisar district of Haryana, some 150 km away from Delhi. To some it might look like a dull and not-so-striking village. But archaeologists and scientists say that beneath the layers of mud and dirt here, lie answers to one of the ancient mysteries, one that has been baffling mankind for many decades – the Indus Valley Civilisation.

The village is a site of an Indus settlement dating 2600 BC-1900 BC. Recently, archaeologists, who have been studying the site, have made some startling revelations. One of them is that people who lived there 4,000 years ago were equipped to face climate change.

This “unpredictable unpredictability” of weather was discovered by the pattern of year-round farming and crop diversity. These crops were grown in settlements away from the urban hub (of Rakhigarhi), which received grains of all types from the surrounding areas, the study says.

The study is based on the research undertaken by anthropologists from the University of Cambridge and Banaras Hindu University. The research was conducted under the Land, Water and Settlement Project of Cambridge from 2008 to 2014, which has been publishing its findings based on the research on the Indus Civilisation in northwest India since 2008.

The focus of the latest paper, published in Current Anthropology, is on the agricultural patterns in Rakhigarhi and surrounding areas in relation to the availability of water there.

The paper says that contrary to the general perception, there was no permanent water source in the area and people always dealt with scarce resources. Also, irregular rainfall forced them to grow dry weather crops even in winter. As a result, they became a paddy and millet eating people.

But in times when the area received normal rain both in winter and summer, people grew season-appropriate crops in both seasons. The researchers also found that rice and millets, which were grown as summer crops, were used more abundantly than wheat and barley, grown as winter crops.

This indicates that the overall condition was summer-like, forcing such a choice. The study argues that this diversity in behaviour, particularly in the proportional exploitation of winter and summer crops, “may have made it possible for populations in some areas to adjust to the dramatic weakening in monsoon rainfall after 2200–2100 BC”.

The revelation puts a question mark on the theory that lack of water and climate change finished the Indus cities and the civilisation itself.

What the study shows is that this cropping pattern of diverse crops was prevalent before the urbanisation of Indus Valley and continued after the de-urbanisation trend. The urban phase in the valley is believed to have been from 2500 BC to 1900 BC, after which de-urbanisation set in.

The fact that Indus people grew a dry weather crop like millet round-the-year also underlines their skills to adapt to lack of water. “Millet appears to have been the dominant crop in all phases at both sites, and rice is the second-most abundant crop at Masudpur I (in Rakhigarhi), appearing in higher quantities and proportions than either wheat or barley. It is confirmed that summer crops were being used alongside winter crops before, during and after the existence of the Indus urban centre at Rakhigarhi,” the study says.

The study’s lead author, Cameron Petrie from the University of Cambridge, says: “Indus civilisation didn’t collapse, but de-urbanised and migrated due to climate change.”

Commenting on the diverse cropping, Petrie says that this is another valuable lesson for farming monoculture, which is being practised today. Monocultures may not be a good idea when the world is facing climate change and unpredictable rainfalls.

Last year, Petrie’s team published startling findings that rice cultivation may have begun in the Indus Valley before anywhere else in the world. It was believed that rice cultivation was domesticated by the Chinese 2,000 years ago. But the Indus sites gave evidence of rice cultivation prevailing at least 430 years before that.

Menon is a freelance journalist.

(The story appears in the March 1-15, 2017 issue of Governance Now)