He had great political acumen, stepping in his shoes will be a difficult task for his successor

Uzbekistan president Islam Karimov, who died in September at the age of 78, will be remembered as the leader who steered the former Soviet Republic with political acumen by carefully maneuvering the domestic politics, keeping the western powers at bay and tackling the threat of extremism. Being a close ally to Russia, he had maintained a tough balance of interest with the western powers towards a gradual economic and political transition. He ruled a geopolitically important country in Central Asia with a firm hand, challenging and surprising his critiques. What puzzles many observers is that despite domestic problems and issues, Karimov maintained stability and peace in the region and pursued an economic growth policy that has puzzled many [see, Zettelmeyer, J. (1999): The Uzbek Growth Puzzle. IMF Staff Papers Vol. 46, No. 3, Washington, DC.]. This has received attention also among observers (namely, the West) to rethink their engagement strategies with countries with different political orders.

Uzbekistan, the most populated country in the region, in fact is a rather young country which got its present borders more or less established in 1924-26, during the time it was annexed into the Soviet Union. Unlike clans that have traditional legitimacy and hereditary succession, clans in Uzbekistan are built around the position of the leader and his ability to draw on legal structures of state bureaucracy and administration [see, Ilkhamov, A. 2007. Neopatrimonialism, interest groups and patronage networks: the impasse of the governance system in Uzbekistan. Central Asian Survey, 26(1), 65-84]. In Uzbekistan, clans are loosely organized groups that are bound by kinship, friendship, patron-client and client-client partnership. There are about seven major clans that are dominant in Uzbekistan. Of them, three hold the most power – the Tashkent, Samarkand and Ferghana clans. These three dominant clans also represent the regions with higher population density or economic potential. Karimov was said to have belonged to Samarkand clan which represents the ethnic Uzbeks and Tajiks. The clans from Ferghana are from the densely populated regions that borders with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Since the region shares borders with volatile countries, a clan derives its power from its ability to control the borders. The Tashkent clan represents the people from Tashkent region, who are educated and affluent, and Tashkent is the most industrialised urban centre. How these clans operate and how their powers are negotiated remains cloudy for the broad public but Karimov’s ability to manage the clan politics was often considered by his critics (mostly from Western countries) as authoritarian. Nevertheless, his governance resulted in internal political and socio-economic stability together with regional security.

Failing to understand the complex power dynamics, western powers have tried to impose their logic of democracy and human rights values on landlocked Uzbekistan, but without much success. They were, in fact, reprimanded constantly as any interference in domestic politics was not appreciated. In a few cases, representatives of Western powers had to leave the country, for example, after a popular uprising in Andijan in May 2005 (probably because of US interference). Following this uproar, the US military airbase in Uzbekistan established after 9/11 was shut down and the West imposed sanctions. But the relationship was not frozen for longer periods, as Karimov reconciled and the West relaxed its arm-twisting measures which resulted in, among others, access of US troops in Afghanistan again. Karimov did not mince words in declining Western calls for implementing democracy and human rights as they operate in the West. And, indeed, one can argue if the western vision of democracy can be applied in countries which have their own historical, social and cultural roots of governing with peace and stability. Obviously, democracy takes time to gain ground depending on capability of people to accept it.

Taking into account such contextual factors, Karimov elaborated the ‘Uzbek’ model of development in the years following independence outlining his perception of a gradual transformation of Uzbekistan as a democratic republic. Later, in November 2010, he called for a further deepening of democratic reforms and development of civil society. Since the millennium change, the Uzbekistan government has been credited for numerous, people-centred initiatives, including water management, environmental protection and public health. Furthermore, one has to acknowledge that the Uzbek economy has shown more resilience to the more recent worldwide crises, like the food crises since 2008, than often acknowledged. The country’s growth is not only export-led (e.g., by the cotton-fibre export), but also supported by carefull investments in infrastructure (machinery, buildings, roads) althougth admittedly implemented by state-directed firms benefiting from the state subsidies, the sheltered markets and politically-driven loans. Through subsequent reforms, Karimov ensured the sustenance of such activities as well as their effectiveness and efficiency, which spread awareness for democratic forms of governance. Improving accountability and transparency remains a prerequisite for ensuring peace and well-being in the country. Karimov’s ability to tailor international discourses of democracy-based development interventions towards a desired change in regional and local context makes him a crafty statesman.

In addition to addressing the internal complexity, Karimov played his cards strategically in protecting the country, the only one in Central Asia that borders all four others, from security threat hovering around the borders. It aims to strategically gain grounds as the regional leader in central Asia. It has good ties with energy-rich Kazakhstan, the economic powerhouse in the region. Both countries are mutually dependent and regional trade partner. Given its transit corridors, its relationship with Turkmenistan has remained to a large extent cordial. However, its regional ties with Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have remained a challenge, though in recent years the relationship with the latter has improved with the inauguration of Emomali Rahmon in Tajikistan. The relationship within the central Asian countries remains a challenge namely in the field of transboundary water, growing extremism and regional infrastructural development. The country faces two major global destabilising factors emanating from across the Afghan borders – drugs trafficking and radical extremism. In recent years these are compounded with Russia’s strategic positioning in Turkey and Ukraine, global positioning of China, European Union and United States. What made Karimov a statesman was his ability to maintain peace and stability in the region, despite the concurrent shortcomings in the quality of life.

The political acumen with which Karimov transformed the former Soviet Republic remains a challenge for his successor. As Uzbekistan deals with emerging political, security and economic challenges, a difficult task lies ahead for the next-in-line president who will be elected on December 4. First and foremost, s/he has to accomplish the goals set by the former president and secondly gain the confidence from the Uzbek people for whom Karimov stood as ‘Father of the nation’. Third, the incumbent has to balance between regional, national and international priorities to gain political and economic stability.

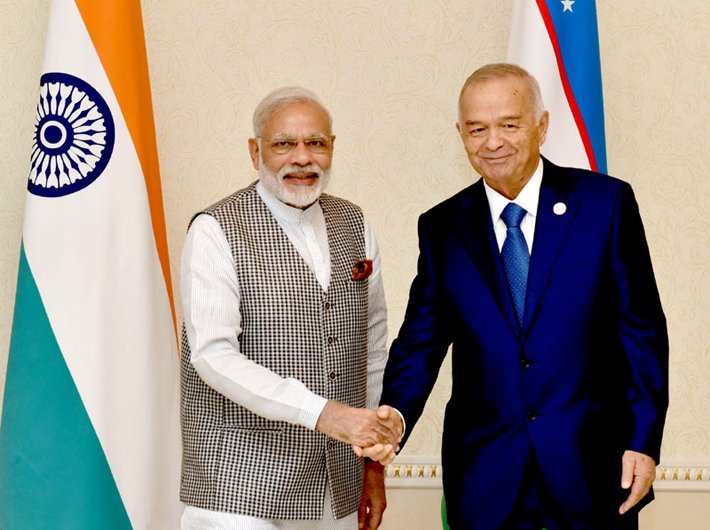

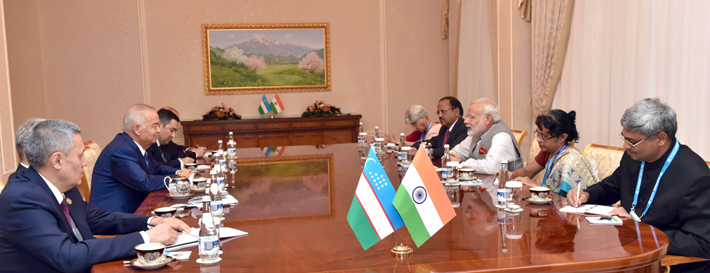

India has a long-standing relationship with Uzbekistan that is historically rooted. Babur, who founded the Moghul Empire in South Asia, originated from Ferghana, Uzbekistan. Such relations strengthened small towns such as Ferghana, Samarkand and Bukhara, which later emerged as major towns and part of the famous Silk Road exemplifying the trade linkage between India and Europe. During the period that Uzbekistan was a Soviet Socialist Republic and part of the USSR, India kept its close political and cultural linkages with Uzbekistan, which is subsequently strengthened through diplomatic exchanges. In 2015, prime minister Narendra Modi headed an extended delegation to seal enhanced strategic, economic and energy related agreements in addition to key regional issues prevailing in Afghanistan. It is important for India to move beyond the current engagements with Uzbekistan towards infrastructure, higher education, entertainment industries and health care. The Lal Bahadur Shastri Centre for Indian Culture in Tashkent should be mandated to play a more active role through academic exchanges of faculties and students. It is important for India to extend these to visual communication, film technology, humanities and natural sciences – and this amid the declared vision of China to revive the Silk Road. But also the plea by countries such as China as well as the EU for Uzbekistan’s treasures including gas, energy, precious stones and recently also oil, will keep on rising which remains a challenge to India. Academic exchanges and sandwich programmes among institutions can significantly boost the educational sector in Uzbekistan. In addition, health care remains an area for strengthening cooperation. Strengthening these areas will facilitate Uzbekistan’s political and economic transition.

The author is a noted scholar engaged in research and education in the Central Asian countries.