Karl Marx once asserted that “history repeats itself, first as a tragedy and, second as a farce.” The observation is valid to this day when one observes the behaviour of dominant and rising powers in relation to other nations. The great powers have the tendency of inflicting ignominy on the other nations. The European powers inflicted the ignominy of imperialism over much of the world, including China in the 18th and 19th century. The Chinese are doing the same in the 21st century.

The year 1500 marks the divide between western and oriental world. No one was aware that the inhabitants of Europe were about to dominate the world. The period before the 15th century saw the rise of the orientalist empires with extensive wealth and armies. The orientalist empires were great centres of cultural and economic activity. Of all the orientalist empires, none appeared more economically advanced than that of India and China.

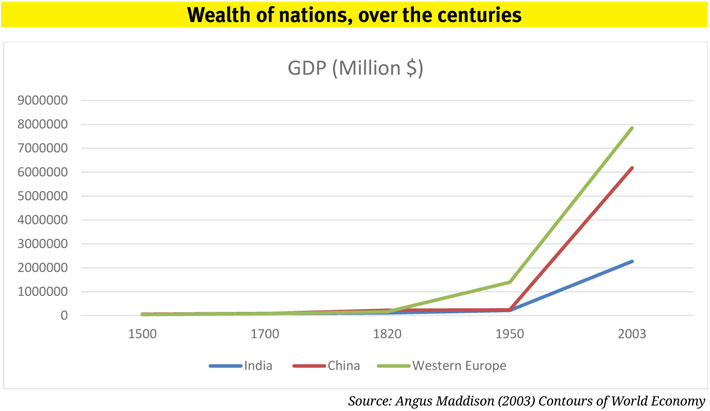

In the pre-colonial period, China and India were the world’s leading economies in terms of GDP. They outperformed Europe in levels of technology and governed vast territorial empires. However, Europe from the start of the 1500s began to prosper owing to technological advancement and the Renaissance that provided foundations for the scientific and industrial revolution. From the 1840s to 1950s the economic performance of India and China declined, and the economic progress of Europe embarked the path of ascendancy.

After the end of European imperialism in the 1950s, China has been transformed in a catch-up process which will continue for the next few decades. The foundation of Modern China, embracing principles of market capitalism, liberalisation and globalisation are associated with the reign of Deng Xiaoping. China under Deng had chosen a middle path or a hybrid of Free-market capitalism and communism called ‘the Chinese Model’. The model transformed the Chinese economy, and growth rates witnessed a sharp increase from 5 percent during the 1970s to more than 10 percent between 1990 to 2008. In a short span of 30 years, China has become the global hub of manufacturing and lifted close to 800 million people out of poverty.

The double-digit economic growth has led to resurgence of China on the world map. The present leadership in China under Xi Jinping has announced a ‘Chinese Dream’ of achieving ‘two 100s’: China of becoming a “moderately well-off society” by 2022 and of becoming a “fully developed nation” by 2049, the 100th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China. The global initiatives like Belt and Road Initiative, Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank, New Development Bank and Chinese investment in countries of Africa and Indian Ocean region are strategic ways of fulfilling ‘Chinese Dream’. Through these initiatives, China is planning to become the world’s next superpower.

The proponents of the ‘Asia on Rise’ theory are of the view that the Chinese are changing the rules of globalisation by offering the world a new form of Chinese-led globalisation with features like expansion of trade, infrastructure lending, new multilateral institutions like AIIB, NDB, long-terms loans to developing countries through China Development Bank, Internationalisation of renminbi, promoting South-South economic system etc. They argue that as the dominance of the Brettonwood institutions and Washington Consensus is receding, the Chinese are offering a new global order to fill the gap.

However, in reality, Beijing is practising a neoimperialist strategy. The imperial advances started soon after the 2008 financial crisis that has given a strategic opportunity to China to increase its global influence and in the autumn of 2013, Chinese president Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) comprising the land-based economic belt and maritime silk road to integrate Eurasia and China through trillion dollars of investment.

Chinese loans under BRI are provided at enormously high rates and without any transparency. The debtor nations often have to surrender their important strategic assets and sovereignty to China. Just as the European powers used military force to open new markets and colonised the world, Beijing is using geo-economics instruments of debt, loans and infrastructure financing to advance its strategic interests. Observers have argued that Beijing’s strategic approach is ironic. Beijing is replicating the same practices that were used by Britain and France against many countries including China. China bitterly calls this period its Century of Humiliation. However, Beijing through its predatory debt policies is establishing its own form of neocolonialism.

Its lending for BRI comes with stringent conditions; loans are collateralised by strategic ports, mines and other natural assets. Beijing follows a policy wherein it demands access to strategic ports, mineral resources, natural resources as a precondition before granting loans or building infrastructure. For instance, in 2002, Beijing has initially proposed to build a port in the fishing town of Gwadar in Pakistan. In April 2015, Xi Jinping escalated the scale of agreement and announced a multi-billion economic corridor, and by 2017, the project has been converted into a $62 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The initial assumptions were that the CPEC would transform Pakistan’s economy. Pakistan does witness the highest GDP growth rate in the last decade due to investment in CPEC. However, CPEC is heavily tilted towards China, and with CPEC it has secured an alternative route to transport oil and goods from the Middle East. The newly elected government in Pakistan has recently admitted that they are under a lot of financial stress and approached the IMF for relief. This crisis has been the result of the deals its struck with China, mainly the CPEC. Pakistan’s CAD has risen to more than 40 percent due to Chinese imports.

Similarly, China has invested heavily in Malaysia as part of BRI during Najib Razak reign. However, due to the huge cost of the projects and opaque provisions, in August 2018 Malaysian PM Mahathir Mohamad had to cancel $20 billion east coast rail link, a project under BRI. Similarly, to help debt-ridden Djibouti, Beijing stepped forth and provided initial lending. However, in exchange, it established its first military base in the strategically located country in July 2017.

The ‘String of Pearls’ theory originally proposed by the US department of defence evidently reflects the scale of Chinese imperialist plan. The theory states that China is trying to establish strings of naval bases across the Indian Ocean and coastal African countries to guard shipping routes and trade. The ‘Strings of Pearl’ countries to which China has decided to lend are vulnerable and will face problems in repaying the debts. Despite this, China has continued to lend because it has greater vested interests in acquiring strategic assets of the indebted countries when they are unable to meet their repayment obligations to China. For example, China loaned $1.5 billion for a new deepwater port in Sri Lanka. By 2017, the loan amount increased to $8 billion, and it was clear Sri Lanka could not pay back the loan. As a result, the Sri Lankan government had to lease out the port of Hambantota to China for 99 years. Beijing is attempting to sign similar agreements and control more such ports in countries like Myanmar, Maldives, Bangladesh and Cambodia. So even though China is not getting its money back, it is achieving some very significant strategic goals.

Thus, it is clear that Beijing is acting in the same manner as the European power once did. China remembers its Century of Humiliation and has vowed never to face it again. It is, however, inflicting the same ignominy on other, smaller nations. The behaviour of dominant powers – be they Britain, the US or China – is reminiscent of Marx’s observation on history.

Himanshu is a young professional with the economic advisory council to the PM. Views expressed are personal.

(The article appears in November 30, 2018 edition)