Can de-linking education and profession in architecture courses help in its better regulation?

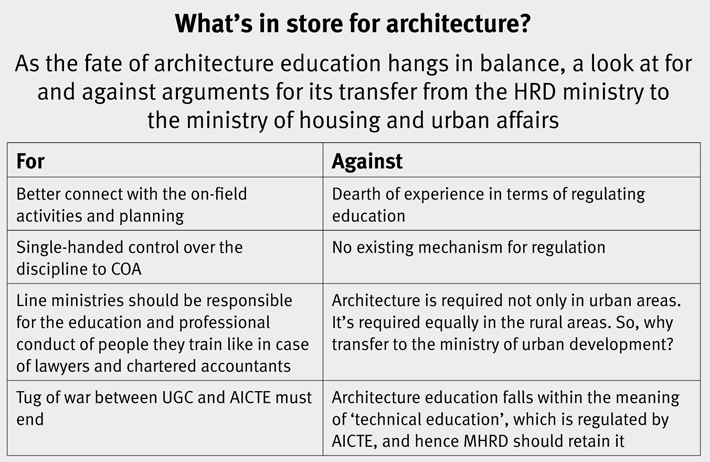

The ministry of human resource development (MHRD) is likely to lose control over architecture colleges and institutes in the country. The proposal to transfer their reins from the MHRD to the ministry of urban development (MoUD), now called ministry of housing and urban affairs (MoHUA), was announced earlier this year by the cabinet secretary. The proposal calls for reallocation of the Architects Act, 1972 and Council of Architecture (COA) – established by the Architects Act – to the MoUD. The transfer has been recommended with a rationale that the profession will have more relevance with the ministry which deals with building activities and planning in urban areas. MHRD may also lose control over the prestigious School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi, as the government has reportedly accepted MoUD’s proposal to transfer the School of Planning and Architecture Act, 2014 too.

These developments have certainly caught the MHRD off guard, which has been also asked to hand over four schemes funding polytechnics to the ministry of skill development. Even though HRD minister Prakash Javadekar recently claimed that “ministries do not fight over territory” in this government, it looks like his ministry is leaving no stone unturned to retain architecture education, which has been its Achilles’ heel since early 2000s.

In March, The Indian Express reported that the then higher education secretary, VS Oberoi, had made a case against the impending transfer, arguing that the architecture education falls within the meaning of ‘technical education’, which is regulated by All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE), and hence MHRD should retain it. However, the COA, which is empowered by the Architects Act to regulate architecture education, has pushed for its relocation to the MoUD. These disputed claims by COA and AICTE have formed a ground for a legal battle between the two that has ensued for over a decade, and is also considered to be one of the main reasons behind the proposed transfer. While the matter of the regulatory overlap remains sub-judice in the supreme court till date, many point fingers towards the MHRD for not resolving the dispute between the two regulatory bodies.

Regulatory overlap

The COA, which came into force on September 1, 1972, has the power to make regulations that may provide for “the courses and periods of study and of practical training, if any, to be undertaken, the subjects of examinations and standards of proficiency therein to be obtained in any college or institution for grant of recognised qualifications”. The council is also empowered to look after the standards of architectural education – in terms of quality of staff, equipment, facilities, training and accommodation. It solely holds the right to register the architects, issue licences to architecture graduates, enabling them to start working as professionals. While the regulation of the profession is entirely with the COA, regulation of the education is something it has been forced to share with another national-level regulatory council – AICTE.

Founded in 1945, AICTE is responsible for “proper planning and coordinated development of the technical education system throughout the country, the promotion of qualitative improvement of such education in relation to planned quantitative growth and the regulation and proper maintenance of norms and standards in the technical education system and for matters connected therewith.” The AICTE Act includes architecture education in its definition of ‘technical education’ – bringing it under the purview of two regulatory bodies (COA and AICTE).

The Architects Act mandates appointment of two AICTE nominated persons as COA members to ensure better coordination. There was a memorandum of understanding (MoU) as well, signed by the two bodies for joint inspection and mutual acceptance of recognition and revalidation, which was terminated in the early 2000s by the AICTE. Notices claiming that they alone have the jurisdiction over control and regulation of the discipline of architecture were sent out by both the bodies and the architecture colleges were asked to apply to them for recognition or revalidation by both of them individually. Both the parties have approached the judiciary on a number of occasions since then. The COA had succeeded in achieving an order in its favour from the Madras high court in 2003, but the issue of the regulatory authority still remains unresolved and is now pending in the SC.

Balbir Verma, former president of the Indian Institute of Architects (IIA) and a former member of the COA, says, “Maybe, an MoU was signed at that time because, sometimes, when there is a new body, they get into an MoU with the people who have expertise in, I would not say architecture, but expertise in procedural systems for regulating education. There was nothing wrong in having the MoU when the council was just establishing. But now the council has its own set procedures.”

Jagan Shah, director, National Institute of Urban Affairs, and former director, Sushant School of Architecture, says that this confusion has had a grave impact on the functioning of the architecture colleges, as they have to report to two different masters. He says, “One or the other body is creating pressure on the architecture institutions, which is quite unjustified pressure.” He further notes that the problem is compounded for the architecture departments of different universities. “In that case, there is a third regulatory body, which is UGC. There are so many regulators then, all their [architecture department heads’] time is spent in dealing with them, rather than focusing on quality of education,” says Shah.

Mohammad Ziauddin, head of the department of architecture, Jamia Millia Islamia University, agrees with Shah. He admits to the confusion, but feels that UGC has the most critical role to play. “We’re paid by UGC, so we’re bound to follow UGC regulations, rather than COA’s,” he says. Ziauddin, however, feels that some of the UGC guidelines are not fit for a professional course like architecture. “For example, according to the UGC’s guidelines, some posts require a minimum qualification of PhD, which is nowhere mentioned in the COA’s guidelines. And it’s difficult to find professors who have pursued PhD in architecture. This is not that kind of a field. Some of our professor-level posts are still vacant because of this impractical requirement,” he says.

This tug of war between COA and AICTE led to an uproar in 2014, when 116 architecture institutes featured in the list of unapproved institutes by the AICTE, as COA claimed that the colleges were under its control. The then COA president, Uday Gadkari, claimed that AICTE had nothing to do with the architecture institutes, while the then AICTE chairman tried to tighten the grip by reiterating that the BArch course is a technical programme.

“It continues to happen, unfortunately,” admits Anil Sahasrabudhe, chairman, AICTE. He claims that since he has taken over, he has tried to extend an olive branch to the COA, so that the two bodies could work together. “As long as the ultimate authority is not declared, why can’t we do it [the inspection] together? Whatever you claim are your regulations, you come and discuss with us. We’ll discuss and iron out the differences. Whatever is suitable, we’ll first agree to that. As long as we do not have vested interests, we should be able to go to a college together, and find out the truth about it. If our inspection is common, our decision will also be most likely common too,” he suggests.

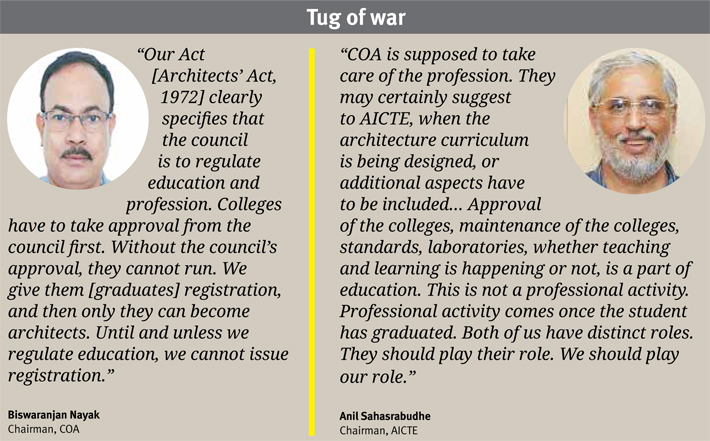

However, it is not likely that Sahasrabudhe’s approach will help mend the differences between the two, as he believes that COA should be focusing on the regulation of the architecture profession. He says, “That is a mistake that they are committing [wanting the full control over the architecture institutes]. COA is supposed to take care of the profession. They may certainly suggest to AICTE, when the architecture curriculum is being designed, or additional aspects have to be included, I welcome that. Approval of the colleges, maintenance of the colleges, standards, laboratories, whether teaching and learning is happening or not, is a part of education. This is not a professional activity. Professional activity comes once the student has graduated. Both of us have distinct roles. They should play their role. We should play our role.”

COA chairman Biswaranjan Nayak is equally adamant that it is his organisation that has power to regulate architecture education. He says, “Our Act [Architects’ Act, 1972] clearly specifies that the council is to regulate education and profession.

Colleges have to take approval from the council first. Without the council’s approval, they cannot run. We give them [graduates] registration, and then only they can become architects. Until and unless we regulate education, we cannot issue registration.” Nayak feels that the COA should have single-handed control over architecture discipline.

This unending strife is considered to be one of the reasons behind COA’s intention to move away from MHRD, and in turn AICTE. “Our profession is more related to urban development, so it would be convenient to have our profession in the urban development department. That is why the proposal was submitted by our council – by my predecessor,” says Nayak.

While the verdict of the case between COA and AICTE is awaited, many feel that the MHRD should have been able to resolve the conflict long ago. It is believed that the COA has been cornered by the MHRD, as the ministry has sided with AICTE more often than not. “Given the fact that both the parties report to the MHRD, it is only fair to expect that in all these years, the MHRD should have resolved this conflict. You cannot leave it to the council to resolve it,” Shah feels.

R Subrahmanyam, additional secretary, technical education, MHRD, says that attempts are being made to resolve this conflict. He acknowledges that the problem is arising because of the conflicting provisions in the two Acts. “The ministry can only administer an Act, but if the Act itself is faulty, you need to change both the AICTE and COA Acts. You have to remove this regulatory overlap,” he says. The ministry is planning to come up with a solution, he says, which will redefine the regulation lines and will ensure that the architecture education remains with the ministry.

Profession vs education

In the past, a number of commission reports have insisted on keeping the higher education of different subjects under one umbrella. While the Kothari commission (1964-66) had insisted on treating higher education as “an integrated whole”, the Yashpal committee (2008) too had highlighted the same principle.

However, the Medical Council of India (MCI), which looks after medical education, is affiliated to the ministry of health and family welfare. Those advocating the transfer of architecture to the MoHUA, usually cite the MCI model as a justification. Shah explains, “[M]HRD has relevance with education, but then architects’ education is not the same as the liberal arts degree. Because it’s the education for a professional degree, where the profession is a regulated profession – where you receive a licence after the completion of your education. That’s a crucial difference. I can say that even engineering is not regulated in the same manner. There’s no regulatory body for engineers. But, here we have an Act that regulates the profession.”

Subrahmanyam, however, feels that the example of the Bar Council of India is more appropriate in case of architecture. “So, the COA [should be] trying to improve the competence of people who have already registered – like the Bar Council. Unfortunately, they [COA] are thinking in terms of the MCI kind of a model. That’s a very wrong example to take, because in medical education, there is no regulator. There is the same professional body, which is doing both jobs.”

The solution, according to Subrahmanyam, is to separate regulators for architecture education and the profession. He believes that these are two separate parts, which need to be controlled in two different ways. The ministry has taken steps in this direction. Subrahmanyam says that an amendment bill related to the issue, which was pending in parliament, was recently withdrawn. “We will present a comprehensive bill for amending the COA Act. We’re in discussion with the COA and AICTE officials. There has to be two separate bodies – one for regulating profession and one for regulating education. The body regulating the profession can go to MoUD. That’s not a problem.” However, transfer of architecture education out of the MHRD is, as expected, not a welcome idea for the ministry, definitely. “If the body, which has nothing to do with education, is regulating education, then there could be issues of coordination. Finally, we can address and overcome any difficulty. There just has to be a firm reason why it should happen then. The point is that architecture is required not only in the urban areas. It’s required equally in the rural areas. So, why are we transferring into the ministry of urban development? And I don’t understand the logic. Even when it comes to the profession regulation also, how can we presume that all the architects practise only in urban areas?” questions Subrahmanyam.

Sahasrabudhe, on the other hand, feels that even if the architecture education goes to the ministry of urban development, the colleges will have to continue to apply to AICTE for approvals. “The new ministry will not create another infrastructure for doing all this, no?” He agrees with Subrahamanyam’s proposed solution to separate education from the profession, even though several senior architects don’t.

Nayak is of the opinion that in case of professional courses, the education and the profession are interdependent. “In fact, all the professional subjects should be treated like that. The government should give full autonomy and support to the autonomous regulatory bodies,” he feels. He disagrees with the argument that the architecture should not be confined to urban areas, as according to him, architects’ role is more prevalent in cities, and in MoUD architecture will have more importance than it has in MHRD, he feels.

Some of the experts believe that the transfer of the architecture education and profession to the MoHUA will ensure “closer synergy and a closer connect between the needs of urban development and the output of architects”. Shah feels that if architecture education is regulated by the MHRD, it may not necessarily have an understanding of the domain in which the architects function.

Verma, however, has a different take on this subject. He worries that if architecture is shifted to the MoUD, the new ministry will not have any paraphernalia to deal with architecture education. “MoUD does not have experience to deal with [the architecture institutes]. That means, they will have to bifurcate the profession and education, and in my opinion, that is not a good idea.” He also agrees with the argument that it should not be assumed that architecture is only for the urban area. “It is as much required for the rural area. In a way, I’m saying, it’s better if it stays with the MHRD, that is, if education and profession remains together under one regulatory body,” he adds.

While field experts continue to campaign against the separation of architecture education from the profession, it is likely that the COA will be moved to the MoHUA. Will it cost COA its regulatory power over education, or will MHRD end up losing one more subject to another ministry? What new arrangement the architecture colleges will have to deal with? It looks like the solution to the longstanding strife is not exactly just around the corner.

pranita@governancenow.com

(The article appears in the October 15, 2017 issue)