Nehru refused to fall for the intoxicating glamour of infallibility. Is there a reminder here for our modern-day unlettered potentates, who have no modesty but all the arrogance claimed from manufactured crowds?

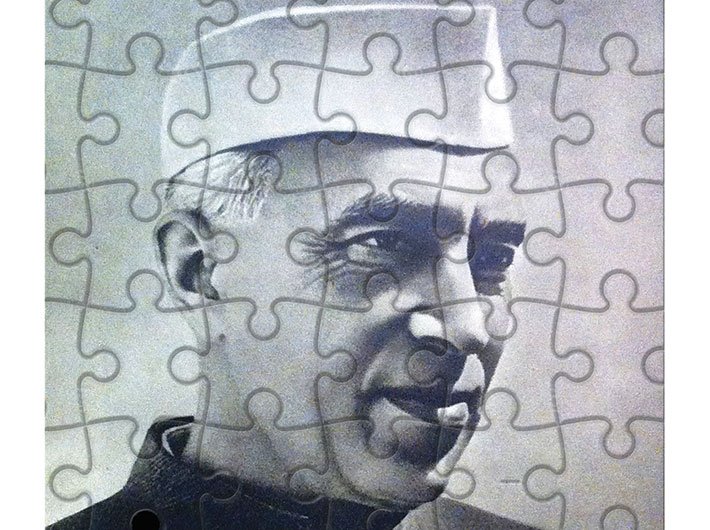

Foreign and Indian observers and historians are almost unanimous in their response to the grand question: why India survived as a democracy after Independence? The answer invariably is a five-letter word: Nehru. Even Jawaharlal Nehru’s most ardent critics, whether on the Right or the Left, grudgingly acknowledge that it was just fortuitous that for the first decade or so after India was fortunate enough to have the man from Anand Bhawan preside over the new government.

Yet, this is somewhat tautological; we still do not fully appreciate why Nehru was different than most other contemporary Asian leaders who opted for less than full democratic paraphernalia for themselves.

Perhaps the answer to this Nehru puzzle was provided by the man himself as far back as 1937.

In October 1937, The Modern Review, of Calcutta, then one of India’s premier publications, printed a stinging attack on Nehru. The author had used a pen name, “Chanakya”. Entitled “The Rashtrapati”, it begins with a dramatic sentence: “Rashtrapati Jawaharlal ki Jai.” It goes on to draw a psychological profile of the man who had been the president (called ‘Rashtrapati’ at that time) of the Indian National Congress for two terms in a row; and, it ends with a plea that it would be a disaster if Nehru were to have a third term. An unsparing portrait of the man and his cunning. [“The Rashtrapati” has been reproduced in Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru, Volume 8, 519-525.]

Interestingly enough, very soon it was revealed that “Chanakya” was none other than Jawaharlal Nehru himself. He had simply scribbled it down as “an after-dinner exercise” and then sent it to Padmaja Naidu, for possibly getting it published.

Apart from being an extraordinary piece of prose, it was amazingly searching self-analysis. Perhaps no other leader in the world in the modern age has favoured us with such a frank, candid and honest assessment of his own leadership, its strength and its potential dangers.

And, what intellectual depth and what scholarly understanding of the global forces Nehru brought to bear on this self-mocking, self-deprecating essay.

Let us remember this was in 1937, and political psychology was yet to become a serious discipline; but, here was Nehru decoding the strange relationship between the leader and the led.

He refers to “the emotion that it [his mere smile] had roused in the multitude” and then wonders aloud whether it was “just tricks of the trade to gain the goodwill of the crowds whose darling he had become.”

He unsentimentally understands his ability to hold, move, motivate and mesmerise crowds, who “cheer him in an ecstasy of abandonment” while he himself stands tall “like a god, serene and unmoved by the seething multitude.”

This is extraordinary. Nehru refuses to be taken in by the ovation; and, he wilfully resists breathing in the wafting aroma of megalomania. He wonders whether his easy and effortless provocation of adulation and hero-worship of the crowd is nothing more than “carefully thought-out trickery of the public man”.

No leader of any substance, leave alone so formidably popular a man as Jawaharlal Nehru, had openly alluded to the contrived bogusness in the relationship with the crowd: “The most effective pose is one in which there seems to be least of posing, and Jawaharlal has learnt well to act without the paint and powder of the actor.”

Now let us recall the temper of the times when Nehru was ruminating. This was the age of disorder and confusion, ideological turmoil and political mischief. This were, to use Hannah Arendt’s evocative phrase, the “dark times”. Nehru penned the Chanakya article at a time when the European liberals were having a difficult time in seeing through the Fascist game. This was the time when both Hitler and Stalin had finessed the mechanism for organised adulation to the last goose-step, last draping of the swastika flag, and to the total command and total obedience: “the relationship between leader and led was also greatly simplified by the projection of an exaggerated leadership image.” These European leaders were assiduously promoting what a historian has called “the myth of infallibility” [Richard Overy, The Dictators: Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Russia, Penguin Books, 2005].

He wrote it before Orwell wrote his 1984 and decoded the psychological making of an authoritarian personality. Nehru had grasped the essential evil nature of a thuggish state.

And, Nehru had the intellectual prescience to understand the historical forces at play around the world and he could sense possible traps of authoritarianism in the Indian milieu. As he put it: “A little twist and Jawaharlal might turn a dictator sweeping aside all the paraphernalia of a slow-moving democracy.”

Let us remember this was the age of fascism and he seemed to be well-versed with the road taken by fascist dictatorships. With a bit of immodesty he declares that he was too much of an aristocrat “for the crudity and vulgarity of fascism”; nonetheless, the temptation was always lurking round the corner. With unnerving anticipation of the postcolonial strong men syndrome in Asia and Africa, he wrote: “He [Jawaharlal] might still use the language and slogans of democracy and socialism, but we all know how fascism has fattened on this language and then cast it away as useless lumber.”

It was this keen and clear-headed understanding of the aberrations and abuses deployed by the dictators and despots that kept Nehru ever vigilant against authoritarian allurements.

Very early in his political career Nehru understood the crowds’ psychology: crowds demand command, direction, goal, and a leader; and, he knew he had the skills for rhetorical drum-rolling to become a dangerous demagogue. Fortunately, he was not only too much of an aristocrat to become a fascist, he had also had marshalled – as his Chanakya deciphered –honest intellectual arguments and genuine insights to proclaim: “We want no Caesars.”

And, as long he was there to steward the new Indian nation, there was never any danger of this or that “Caesar” putting in an appearance. Nehru had intellectually inoculated himself against dictatorial temptations – and, for decades thereafter he sought to tutor the multitudes in their democratic rights and privileges. That is why he was hailed by a contemporary observer as “the ruler who remained disinterested and compassionate” and as an administrator who was “imperious but not ruthless” [Walter Crocker, Nehru: A Contemporary’s Estimate, George Allen & Unwin, 1966]. Nehru remained uncorrupted by power and therefore remained a robust and vigilant defender and promoter of democracy.

Since then any number of apologies have been offered for dispensing with democratic arrangements all over the world. Any number of statesmen-like voices, from Lee Kwan Yew to Henry Kissinger to Financial Times, and a whole host of pro-“growth” votaries have applauded “doers” in Asia who effected “economic miracles” – never mind if it involved cutting a democratic corner here or there.

So let us come back to our original query: why India remains democratic. India remained steadfastly on the democratic course because nearly

75 years ago Nehru had brilliantly decoded megalomania and then refused to fall victim to its spell:

“With an energy that is astonishing at his age, he has rushed about across this vast land of India, and everywhere he has received the most extraordinary of popular welcomes. From the far north to Cape Comorin he has gone like some triumphant Caesar passing by, leaving a trail of glory and a legend behind him. Is it his will to power, of which he speaks in his Autobiography, that is driving him from crowd to crowd and making him whisper to himself:

‘I drew these tides of men into my hands

And wrote my will across the sky in stars.’ ”

Such clarity, such conviction, such wisdom, such enlightenment!

After the Chanakya piece was published, Nehru was chastised by his friend Padmaja Naidu for running himself down. Nehru replied that perhaps her complaint was not unjustified “because you will imagine me as something other than I am, something nobler perhaps, more mysterious, more complicated. Have I not warned you against that fatal error?”

Nehru simply refused to fall for the intoxicating glamour of infallibility. And, that is why he ensured that India spurned the cult of infallibility.

Is there a reminder here for our modern-day unlettered potentates, who have no modesty but all the arrogance claimed from manufactured crowds?